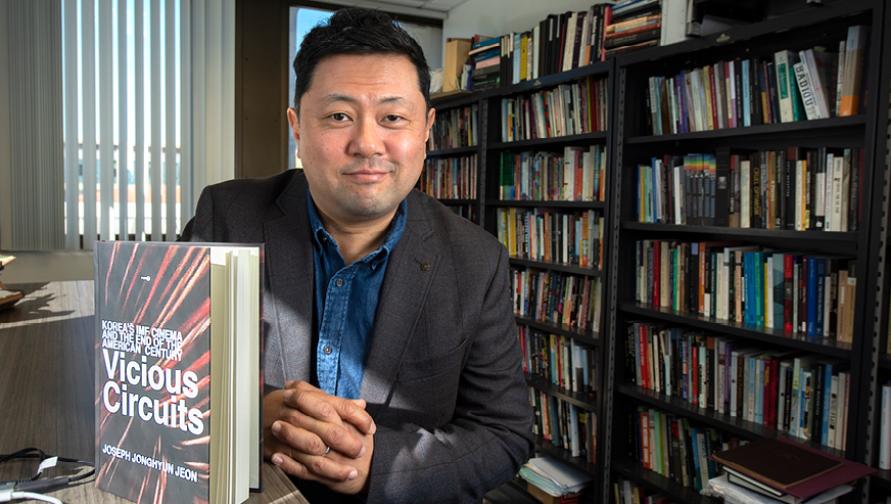

How do filmmakers represent economic crisis in their films and how does the economy itself affect filmmaking? These questions are at the heart of Vicious Circuits: Korea's IMF Cinema and the End of the American Century (Stanford University Press, 2019) by Joseph Jonghyun Jeon, professor of English at the University of California, Irvine.

In Vicious Circuits, Jeon examines what he coins "Korea's IMF Cinema"—the decade of cinema following South Korea’s economic collapse of 1997 when the International Monetary Fund announced the largest bailout package in its history, aimed at stabilizing the South Korean economy. From internationally renowned films like Park Chan-wook’s “Oldboy” to more obscure art films, the proliferation of movies produced during this timeframe share in common their focus, whether explicit or implicit, on economic themes.

Below, Jeon discusses his inspiration for writing the book, what he hopes readers will take away from it and more.

Q. Your book explores the growth of cinema in South Korea after the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Crisis in 1997. What inspired you to explore this topic and this timeframe?

A. In 2004, I watched Park Chan-wook’s “Oldboy,” which had been released the year before and had quickly earned some international notoriety, winning the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. I think I watched it on a tiny 14-inch TV on videocassette, sitting on the floor of a friend’s house in Berkeley, California. But even in these less than ideal viewing conditions, I was blown away not just by the innovative storytelling and brilliant cinematography but also by the way the film explored the pathologies of an iconic figure from the IMF period in South Korea: the salaryman. Because of the sudden and massive layoffs during the crisis, the figure of the troubled salaryman became a common feature of Korean public discourse of the period, hanging around the park all day in their business suits too afraid to tell their wives that they had been fired or, even more tragically, committing suicide by jumping off one of the bridges in Seoul that crosses the Han River. Here was a film that sought to make sense of the extreme anger and frustration that inhered in that figure. Although at the time, I was at work on a book about Asian American poetry, I immediately sat down and wrote an article, which was to be my first publication on Korean cinema. The project has developed and changed over the years, but it really began with that initial viewing of that particular film.

Q. Though South Korea experiences economic instability during this time, it also experiences a boom in Korean filmmaking. What are some of the similarities you see in the movies produced during this timeframe?

A. The argument of the book is that Korean film in the period, what I call “Korea’s IMF Cinema,” isn’t just preoccupied with economic phenomenon in a thematic way but more radically is an expression of an industry that manifests in a material way a political economy shifting away from the high-growth industrial model that had earned South Korea such enthusiastic monikers as “Asian Tiger” or “Miracle on the Han” in previous decades. By the early 1990s, explicit governmental globalization strategies aimed at compensating for slowing economic growth very much included the cultural industries. These are the years during which the Hallyu (or the Korean Wave) begins to gather momentum, and which very much leads into the global popularity of K-pop today. There is a famous story about President Kim Young Sam in 1994 learning that the export revenues of “Jurassic Park” had matched the foreign sales of Hyundai cars that year. In response, the film industry during the 90s was reclassified as a “semi-manufacturing” business. This reclassification suggests its transitional logic, standing between older and newer economic systems in South Korea. So, to answer your question, a lot of these films are self-reflexive about how movies work in relation to the question of how economies work. Because of its particular position with respect to the economy as a whole, filmmaking of the period becomes a particularly useful way for thinking through economic questions. I found that a lot of the movies in the period—whether they are explicitly about detectives, rock groups, or monsters—are implicitly obsessed with economic concerns.

Q. While conducting research for your book, and watching the films produced during this timeframe, were you surprised by anything you found?

A. The most surprising discovery I made was the remarkable depth of the filmmaking in general. I had known about directors like Park Chan-wook, Lee Chang-dong, and Bong Joon-ho because of their international reputations, but I was delighted to discover while I was doing research so many wonderful little films that run the gamut from comedy to art house to action. Films like “Oollala Sisters” (2002), “Foul King” (2000), “Looking for Bruce Lee” (2002), “Helpless” (2012), and there are so many more. Originally, I had conceived of the book as a series of chapters that would each focus on a single film, but as the book developed, I realized that I was also interested in addressing this breadth.

Q. What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

A. Even though the book is about Korean cinema, I think of it very much as an American studies project. The United States has been the dominant global economic power since the end of World War II, and the so-called Washington Consensus has come to define the global economic system since the 1990s. Historically, South Korea is one of the U.S.’s strongest allies; it was, for example, one of the few countries to send troops in the internationally unpopular second gulf war in 2004. But it is also an ally whose economic priorities have shifted toward China, which has become its largest market for exports. So, Korean film and Korea, in general, is a useful site for thinking about the end of the American century and the world system that the U.S. has led for half a century. As I was writing the book, an abiding thought was that, to a certain extent, South Korea is to the U.S. what India was to the British Empire, especially as the empire was coming to an end. Both serve as reflective surfaces for the contradictions that erode global power. My title, Vicious Circuits, refers thus to the imbalances and incongruities that create the momentum for such declines.

Photo credit: Steve Zylius / UCI