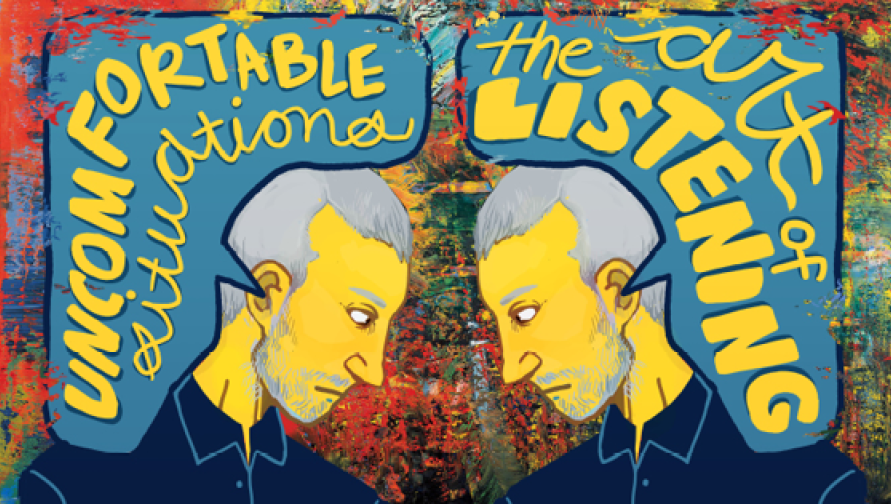

Daniel M. Gross, professor of English and director of composition at the University of California, Irvine, was living in an optimistic California bubble until he discovered a different kind of emotional terrain. During his adolescence, he was fascinated by Berlin painters Gerhard Richter and Rainer Fetting, and devoured literature by Claude Brown and James Carr. He says this sparked “a deep conviction about the variability of emotional life, not just from person to person, but from environment to environment.” The result is his recent book, Uncomfortable Situations: Emotion between Science and the Humanities. Gross is the ideal example of a teacher who challenges his audience with personal questions, connecting the inner monologues of his students to the outside world.

Now, he’s tackling the other side of language – listening. His current book project, Being-Moved: Rhetoric as the Art of Listening (forthcoming from UC Press), explores when and where the art of speaking parted ways with the art of listening – and what happens when they intersect once again. Here, we discuss Gross' research projects.

Danielle McElroy: In your book Uncomfortable Situations you reference Darwin and the limits of science for providing means of understanding human emotion. Do you still feel this is the case?

Daniel Gross: I am more convinced than ever that this is an important project for people to work on, and I'm thinking of it in the following ways. Let's take rhetoric, my home discipline in the humanities, as a kind of field guide to human environments. That gives us in the humanities something to share with folks who work in the social and natural sciences – we all share research interests in "human environments" – what they are, and how they can be lived. To give you an example from my work in emotion studies, the natural sciences, biology, cognitive psychology talk about basic emotions – joy or happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise and disgust – and the way that those emotions are understood in biological terms connecting us to our ancient ancestors. From this perspective the relevant "human environment" is something that we share with our ancient ancestors who had similar brains, going back to the Pleistocene 10,000+ years ago. So fear is understood as a response, let's say to a coiled snake, disgust to a food that is bad for us or poisonous, and joy, let's say to honey, something that tastes good and is highly caloric. That must be right in some basic way, but you'll see they leave off the list of basic emotions something like love, or jealousy, which seems counterintuitive to anyone, and especially for people working in humanities where we have spent so much time writing about and thinking about love, including romantic love. What do we all do with that? How do we understand the human environment if it only, in serious scientific terms, treats a biological environment where survival and adaptation are the factors that produce basic emotions? How do we think about something like romantic love, or jealousy, in a way that takes seriously in this case a human environment that isn't reducible to procreation strategies? It turns out Darwin was really sophisticated in this way.

DM: How can students take inspiration from Darwin's book The Expression of The Emotions in Man and Animals?

DG: His 1872 Expression book is just a pleasure to read; it's beautifully illustrated amongst other things, and it is the first published scientific book that uses photographs that were carefully inserted into the first edition to demonstrate and represent different sorts of emotional expression. Now, Darwin’s book is typically taken up by Paul Ekman and others, recent scientific psychologists, as a kind of confirmation of the basic and universal emotion theory, but in fact Darwin is also doing all sorts of really interesting and humanities-related work on emotional expressions.

He’ll discuss for example, devotion, which doesn't sound like an emotion to us, and he describes how in his context, devotion – namely a kneeled posture and clasped hands – might seem universal. But if you do historical and ethnographic research, he argues, that turns out not to be the case. What he’s doing with an example like that is critiquing the immediate response one has to an expression of emotion, which might seem natural, universal, everyone would understand it, unmediated, right? He’s doing a kind of historical critique, reading literature and doing work that demonstrates that our immediate reaction, our immediate emotional reaction is local, and can’t be extrapolated easily beyond our more local environment, or his, in this case. Darwin does that regularly in the book: his images include photographs that are staged – staged expressions – and etchings, there’s a famous, wonderful etching of a chimpanzee disappointed and sulky when an orange is offered and then taken away, and part of the effect of that illustration is that you respond to it as a reader. You see this illustration and you think, ‘that’s cute!’ Right? It looks cute, there’s this pouty chimpanzee and that is, in itself, a kind of demonstration of his principle, namely that emotions are experienced as immediate reactions, but he’s not giving you what we would call a “face to face experience.” Darwin is giving you an etching that’s drawn from life, that’s in a book – there are many layers of mediation in other words, and he’s interested in how the forms of mediation produce a certain sort of emotional effect, and then he takes a kind of skeptical look at how mediation makes a difference when it comes to understanding our human environments. I think that’s a basic principle that we can take seriously, in the humanities in conversation with the natural sciences, namely, how do we understand local human environments that produce certain sorts of emotion and not others.

DM: What are your hopes for the future of laboratory sciences combined with critical and rhetorical methods from the humanities?

DG: The final chapter of Uncomfortable Situations is co-written with a colleague at the University of Michigan, Stephanie Preston. She is an ecological neuroscientist who does both laboratory work and ethnographic work – field work. It was a challenge and hugely educational to write with her because we’re coming from different worlds when it comes to our shared topic: empathy. The collaboration required that we work out a common language and a common kind of framework. What we wound up doing was working on a key point that she had observed in understanding how hospital patients suffering might elicit more or less empathy from their caretakers. She documented the fact that reticence – the performance or the appearance of reticence in the face of suffering – actually elicited more empathic behaviors from caretakers than the outright expressions of suffering. Part of the consequence as she documents, is that in fact, the unwillingness or the apparent unwillingness to foreground your suffering, turns out to be for us now, a marker that elicits empathy "immediately." When you’re studying in a lab, you're doing work in the field at a hospital, you need to isolate variables so that you can produce differential results – in this case more or less empathic responses given variables that are controlled. The causality, the reasons for the difference, comes in the discussion part of the scientific article.

Now, natural scientists are vary wary of making broad claims for causality in a case like this, but the cat’s out of the bag because these are studies that wind up in the popular press, they get picked up to explain how we are, who we are, in all sorts of ways. Causality is inferred or interpreted by a general public or popular science writers, hinted at in the research reports themselves, but then played out on the public stage, and that's where we need to slow down and be careful about how our interpretations sound – what we’re doing with this information. That's one place where people in the humanities can be deeply helpful. Ultimately our argument in that co-authored piece connects the reticence/empathy dynamic to the research of historian Carolyn J. Dean, who tracks the rise of this same emotional dynamic after a series of false victim scandals in the 1980s. To fully see the connection you have to read the chapter. The larger point is that the reticence/empathy dynamic can be observed and analyzed within a small study frame, but it cannot be understood adequately without a certain history in this case. When it comes to something like empathy, what counts as the relevant "human environment" must be worked out between science and the humanities.

DM: When will your book The Art of Listening be released and what can your readers expect?

DG: Four and a half out of five chapters are written. The connection here to my fundamental research interest is what we call in rhetoric “being moved.” There’s a lot of academic work going back millennia on how things are done from the perspective of the agent in rhetoric, the art of speaking well, writing well, affecting, moving, persuading others. There is also a kind of subterranean history of being moved, and emotion is clearly relevant. Namely, what are the mechanisms by which people are moved? That's the whole emotion studies project. It's also the art of listening project because these are questions about susceptibility, about learning, changing one's mind, vulnerability, the ability to become someone else – issues that are undertheorized in the humanities, especially in my home field of rhetoric. The place where there has been work is around “sacred rhetoric.” So, listening to the Word of God, susceptibility and openness to logos, the “word,” is a deep part of religious traditions. Judeo-Christian, and otherwise – religious traditions are always going to be about subsuming oneself to God’s law, to the will of the gods – there are different ways of thinking about it but it's always from the perspective of susceptibility and making oneself vulnerable, open to transformation. One dramatic form would be Born-Again Christianity, for example – a radical renewing of one’s life, one’s nature: second nature. All of the senses are renewed: taste, touch, smell, sight, hearing. But there are these other moments, let’s say the psychoanalyst is supposed to be a good listener. The art of listening is distributed into popular culture in certain ways. The pop-psychology of “men are from Mars, women are from Venus” has some of that, so it comes out in these reduced forms, but there’s this wonderful story to be told about arts of listening and ways of being moved that I think we could do through the literary humanities, including my own field of rhetoric. That's the project, to focus on what is it to listen differently. The work in Exodus on Moses as a kind of vulnerable character is part of that story; the Parable of the Sower; Psalm 5; and Augustine on sacred rhetoric – these are some of the building blocks for the story, which dissipate in contemporary secular history, without disappearing. I'm doing a kind of archaeological project to rediscover what some of that long history is, and the way in which we are still shaped by it.

DM: Are there any characters in literature that are good listeners and what can we learn from them?

DG: I just mentioned Moses, who is not a good a talker like his brother Aaron, but is a great listener. We will spend some time [in our class] on Donne, Herbert, Milton’s Comus. Of course poets must have wonderful ears, amongst other things, and be sensible at the physiological level to the way in which meter and rhyme work. Also, if Mill was right that “oratory is heard, poetry is overheard," then at least the disposition of listening is distinct when it comes to different modalities of communication. What is it to overhear? Poets, let's say in this case, lyric poets of the 17th century, were absolute masters of working through that problem.

Finally, detective fiction, right? Think about Sherlock Holmes. Part of his art, and this is a very 19th-early-20th century detective fiction forte in a world that was also producing psychoanalysis – the arts of listening have a technological quality, like a phonograph or a recording device. Mechanical, in other words. While at the same time, deeply sensitive to silence. Part of the art that Arthur Conan Doyle produces is about silence and its significance in the domain of activity, right? So how do we listen to nothing significantly – that is part of his art.

DM: I am a student in your class on “The Art of Listening.” Do your students reaffirm things you have learned about the field, do they ever bring up inspiration? Do they ever change what you might want to put in your book?

DG: Absolutely. That’s part of the joy of teaching – it’s really productive for research as well because you just can’t think the same way by yourself. Our class the other day on dactylic tetrameter, right, which runs in this case from the Iliad to Public Enemy, only really became meaningful to me hearing it in class. So there’s a way in which the vocalization and the sound with other people, hearing together, is essential to the experience. One of the students asked "did Chuck D. know he was working in a heroic meter?" In a way, it doesn't matter; it is manifest as a heroic meter but what does that mean? It’s something that’s felt and heard, and it has to be in public, right? Hearing is, amongst other things, not just a personal experience, it's not something that just happens by way of the physiology of the ear. Sacred rhetoricians and preachers in the 17th century were deeply aware of this. There was an injunction in treatises on arts of listening, not just to stay at home and read the bible but to go to church, because the “public ear,” as it was put at the time, hears distinctly. In certain cases you have to hear with others. That’s probably gonna show up in my book, in some form – that kind of performative public quality of, in this case, the sound that’s contrary to all sorts of English usage conventions, but is resonant across, in this case, media and millennia and people. So that would just be one example, there are many many others – it's daily. Every time I go to class, I come out different.

...

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Danielle McElroy is a UCI English major and photographer.

Daniel Gross is a great listener and a professor of English at the University of California, Irvine.

Illustration by Shannon Downer, UCI English major