By Tyrus Miller

It is nearly impossible these days to open a newspaper, magazine or newsfeed without encountering articles on generative AI and its potential impacts on society, politics, the economy, work, health care, education, privacy and more. If, like me, you have consumed a steady diet of such articles over a sufficient period of time, you will have automatically preset the internet to deliver you more and more of the same. For instance, without my prompting, Apple News has recently established AI as one of the specific categories under which it aggregates news stories for my perusal — undoubtedly having used its own AI to do so.

The humanities and generative AI: A delicate balance

In UC Irvine’s School of Humanities, though we are not a school of information science or engineering, we have not ignored these recent developments in technology. Yet I could hardly claim we’ve made giant steps in addressing the common concerns around generative AI either. I myself still feel much of the perplexity I initially experienced first hearing the drumbeat of techno-utopian pronouncements about AI — like the Harvard Business Review announcing on its cover that generative AI inaugurates an era of unprecedented human creativity — in competition with laments that generative AI means the end of the world as we know it and we most certainly should not be feeling fine.

Some School of Humanities faculty and programs, most notably in our writing programs that help prepare large numbers of UCI students in multiple disciplines across the campus, are actively preparing to maintain outstanding instruction in an environment newly inflected by the availability of AI tools capable of producing expository prose at high speed and volume. More broadly, we are working in the school to develop humanities-specific guidelines, recommendations, policies and trainings, with the goal of helping our students continue to study without AI’s promised “disruptive innovation” primarily disrupting cultivation of their capacities to learn, make judgments, express themselves and act ethically in the world.

Beyond technical solutions

But such practical matters will not be the focus of this short essay; they are for another day and another venue. Here I contend that while technical measures such as potential revisions of our pedagogy and safeguarding the data of our students are important, we also need something more and different. Problems of technology, we might observe, are not necessarily technological problems; we may doom ourselves to failure if we seek their solutions only in new and improved technical fixes. In fact, in pursuit of such technical fixes, we may end up evading the real, human problems arising from “pathologies of reason” — to use the philosopher Axel Honneth’s term — built into our societies and even to some extent rooted in the depths of our souls. It is in this human dimension that the impacts of AI matter most, and it is likewise in this dimension that beneficial rather than harmful responses to pervasive AI must be found. I firmly believe, as well, that key resources for framing the right questions and seeking effective answers to the problems reside in the disciplines of the humanities: resources of historical and social analysis, resources of interpretation and resources of creative thought in the media of word and image.

Oh no, not another AI reflective thought piece!

A prominent form among the voluminous popular journalism I’ve read about AI is the reflective thought-piece. Such essays and editorials typically expound the present and future dangers of a world in which AI has become pervasive, or, alternatively, trumpet the manifold ways in which generative AI will render our work more creative, our shopping more tailored to our individual needs and desires, our bodies and automobiles better protected from unfortunate externalities like malfunction, crime, aging and accident. As a scholar of literature, I could easily perceive across these various pieces that authors are establishing and stabilizing a set of new generic conventions, putting the “AI reflective thought-piece” on the path to becoming a mass media genre like the TED Talk, the touching animal rescue story, the cable news woke-atrocity report and the embarrassing celebrity wardrobe-fail anecdote. One of the conventions of this particular genre of writing is that authors often furnish a piece of AI-generated prose at the outset and then proceed to say why, for all its admitted flaws and awkwardness — in any case, soon to be improved upon as the technology inexorably advances and the machine learning deepens — the machine-generated text demonstrates the author’s cherished hopes and fears about the brave new world of AI.

A literary experiment

If you have stayed with me this far into my disquisition, you will have recognized that I eschewed that sort of standard opening for my essay. But here I must make a confession: I considered doing this myself, as a way of jump-starting my thoughts on this topic. With a hint of self-mockery at my vacillations before the empty laptop screen, I prompted ChatGPT to generate for me a paragraph of text expounding the dangers of AI in the pitched idiom of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ Manifesto of the Communist Party, which originally appeared in 1848 amidst popular rebellions across Europe against authoritarian governments, miserable living conditions and social dislocations occasioned by modern industry. Hitting the send button on my ChatGPT prompt, I awaited the output of this deliberate mashup of industrial age criticism with my digital age concerns.

Here was what ChatGPT fed back to me in return:

In the realm of the technological epoch, a specter haunts the domains of Artificial

Intelligence, a specter that unveils the perils embedded within the heart of this

burgeoning force. The bourgeoisie, in its ceaseless pursuit of maximizing profit,

has harnessed the very essence of intellect and innovation, creating a system

wherein machines, driven by algorithms inscribed with capitalist logic, usurp

the labor of the proletariat. The workers, chained to the mechanized yoke, face

the alienation of their craft and the erosion of their agency, as the means of

production metamorphose into the means of oppression. As AI systems grow

in sophistication, a dehumanizing force unfolds, engendering mass job

displacement and heightening socioeconomic disparities. The digital

proletariat, lacking ownership over these technological marvels, becomes

dispossessed and disenchanted, mirroring the historic struggles of the

proletariat. Yet, within this dialectical struggle, lies the potential for a new

synthesis: a harmonious alliance of humanity and AI, where the machines

are subordinated to the collective welfare, obliterating the chains of algorithmic

exploitation and steering towards a future where the marvels of AI serve the many

not the few.

On a first read, though at best an awkward pastiche of Marx and Engels’ stirring rhetoric, the resulting AI.comm manifesto by “ChatM&E” was, in the end, not quite so silly as I had expected. Indeed, some of my own biggest worries with generative AI relate to the irrational process by which we have arrived at this technology’s current horizon, a process that has spurred breakneck development and uncontrolled propagation of tools and domains of application, come what may of damage to our social and political life and of suffering inflicted on individuals who may lose livelihoods, control of creative products and precious civil liberties. One would hardly need to read Das Kapital from cover to cover to see that the AI wave and its supporting media hype have been supercharged by competition between both corporations and states, all scrambling to win advantage over or at least keep neck and neck with their perceived rivals. The same perilous logic of escalation appears to be driving Microsoft and Google and interstate rivalries between the U.S. and China, with no evident point of exit from this vicious spiral. If we are not all in on AI, we are told, all at once and for the indefinite future, there will be mortal consequences to follow. Today is the emergency, time to move fast and break things and worry about sweeping up later.

The politics of AI?

But just as I was settling into agreement with my M&E-bot’s righteous indignation — which of course confirmed my own presentiments — my critical antennae went up again. I asked myself, but isn’t that swift turn at the end of the paragraph from a Mad Max landscape of desolation to happy hand-holding between human and machine just a tad bit facile? Could it be that ChatGPT was actually pulling my leg? Was it being ironic when it evoked “the machines” — that is, itself and its kin — surrendering their powers to the common welfare? Or could ChatGPT still just be a little naïve, whereas some more machine-learning will soon chip the edges off its idealistic pronouncements? Or is ChatGPT really “selfless” and altruistic, even saintly? Can it see what is happening to us and is trying to help? What, oh dear, what was it trying to say to me?

Let’s pause for a short reality check and remind ourselves: ChatGPT can churn out, with equal facility and at equal speed, manifestoes in the style of Pericles, Machiavelli, Robespierre, Bakunin, Hitler, Gandhi, Pope Francis or Donald Trump, switching from one to the other in a matter of seconds with a sublime lack of concern about ideological consistency. Any AI-Marx-and-Engels lurking inside ChatGPT can become an AI-Mussolini in a matter of seconds. What for an actual person would be an extreme act of political conversion, apostasy or self-denial, having profound existential and moral consequences, is for ChatGPT only a few deft keystrokes and the click of a mouse. ChatGPT has no intrinsic political or moral message for us, no matter how often we try to conjure one up on its behalf. But its effects will mirror and magnify those we are already “generating” for ourselves, individually and in the society of others. It thus becomes newly important to deliberate on and try to shape through democratic voice our public discourse. As Hannah Arendt justifiably fretted, we deceive ourselves to think that we can hand over such a task to an impersonal technology, sacrificing the risky freedom to debate and decide things together to the promise of superior predictability and control.

Difficult freedom

The humanities also have something to tell us about the difficulties we encounter in realizing this freedom, difficulties that can tempt us at times to dream of a grand machine that would relieve us of the burdens of error and debate. Public discussion demands that we find out what others think, inviting them to express their thoughts in words and exposing ourselves to the potential unease and conflicts that arise in public discussion. Listening to and answering one another, we find, alas, no end to human misunderstanding, only the infinite task of seeking clarification through more speech. Each of us enters the arena with a multitude of beliefs and prejudices that may unravel in the process of putting up views for debate and criticism.

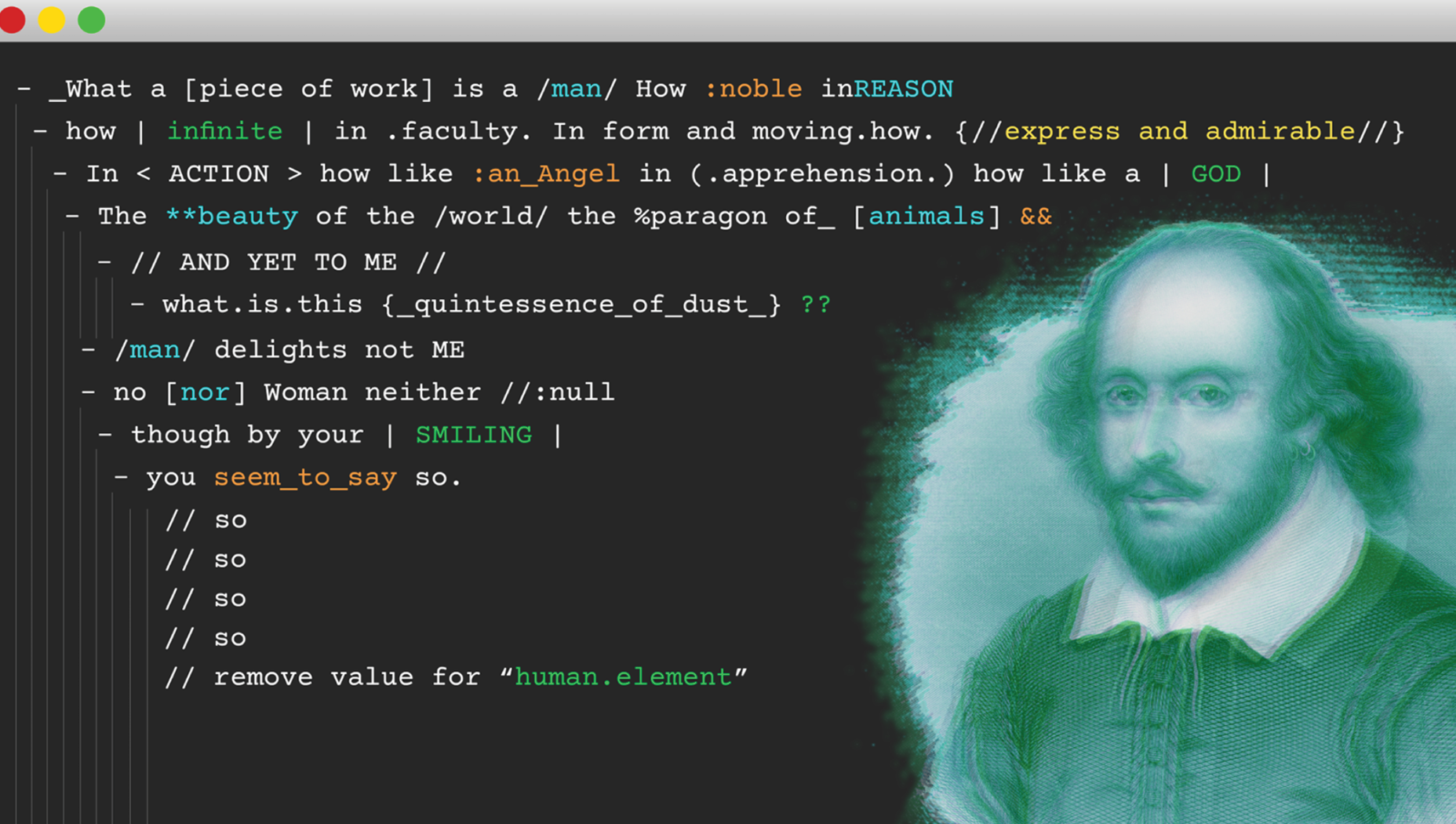

We know of literary works by authors such as Shakespeare, Henry James, Virginia Woolf or James Baldwin among others, that heighten our awareness of the potential tragedy and suffering that can be occasioned by the opacity of others’ motives and the ambiguities of their speech and action. The philosopher Stanley Cavell once claimed that the hoary philosophical problem of skepticism — the debilitating echo of which we find in our “post-truth” mediasphere — is not primarily a matter of the knowability of the external world or other people, but a damaging disposition of the self in its relation to others. Skepticism, for Cavell, reflects our disappointment in and distrust of the ways we actually do know something of one another’s minds: through our words, our gestures, and our acts, which nonetheless will never put us fully in another’s head nor ever will be purged of their ability to be misunderstood, to mislead or deliberately to deceive. We are forced to interpret one another at every turn, with all the possibilities of failure entailed.

The human measure

But what does this all have to do with ChatGPT? I return to the questions I evoked about the would-be “mind” and “voice” behind the manifesto I prompted ChatGPT to generate. Irresistibly — yet also embarrassingly, since I know all too well that there is no homunculus inside ChatGPT, like the little man concealed in Kempelen’s mechanical chess player — I sought to understand ChatGPT’s “intentions.” What does ChatGPT want? What is it after? Is it a friend or a threat? Is it ironic or sincere? Should I trust it?

As such, these questions are meaningless: ChatGPT “wants” nothing and “intends” nothing. But my continual temptation to pose such questions, my attempt to parse these machine-generated words by placing them in existentially and morally significant contexts, is meaningful. Nearly a hundred years ago, in his poem “The Idea of Order at Key West,” Wallace Stevens wrote of the creative process of translating the ambiguous sounds of nature into the human order of the poetic word:

The maker’s rage to order words of the sea

Words of the fragrant portals, dimly-starred,

And of ourselves and of our origins,

In ghostlier demarcations, keener sounds.

Posthumously in his writing, Stevens again gives voice today to the challenge of discovering an analogous human responsiveness to the chaotic murmuring of the machine-made word. This primordial “rage to order” brings us back to the human interpretive practices that ground the disciplines of the humanities, formed in confrontation with the ambiguous and often opaque legacies of human meaning-making across the ages, inviting us to apply them in new contexts opened by a cognitive technology of potentially dreadful proportions. Whether we can take their human measure — meaning their political, ethical and existential, as well as poetic measure — is wholly upon us to answer.

What do we want?

The most urgent question about generative AI should thus not be posed to ChatGPT but to ourselves. Not “What does ChatGPT want?” but “What do we want?” is the essential matter at hand. This is a question of our self-knowledge and our self-dispositions, as individuals, as communities, and, admitting all the difficulties this entails, as a humanity we partake of in common. In the end, however, this brings us back to our public discourse, which offers answers to that question “What do we want?” as an active, contentious, democratic will.

In 1784, in his famous essay “What is Enlightenment?,” the German philosopher Immanuel Kant asserted that enlightenment is—

humanity’s emergence from its self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is

the inability to use one’s own understanding without guidance from someone

else. This immaturity is self-imposed if its cause lies not in any lack of

understanding but in indecision and in the lack of courage to use one’s own

mind without the help of someone else.

Centuries after, Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno reformulated Kant’s idea of emergence from self-imposed immaturity as an active task for contemporary society: “education for maturity.” This seems to me an idea we should continue to affirm and seek to realize in facing up to the challenges of generative AI for our mission as public educators and scholars.

The worst self-imposed immaturity at our present moment would be to leave the critically important questions of who we are and who we want to be up to technologists, investors, military strategists and bureaucrats who presume to be able to speak and choose better for us than we can ourselves, or simply to let the answers to decisive questions be algorithmically generated behind our backs. The first order of the day might be now to arrest, or at least retard, the reckless, unregulated “progress” toward pervasive AI presented to us as inevitable and, come what may, desirable.

Enlightenment today demands we find, amidst the din of machine-made chat, new ways to speak in our own voices, to listen to one another and be heard. We may also discover that its first condition is the courage, at a critical time, to say no.