By Nikki Babri

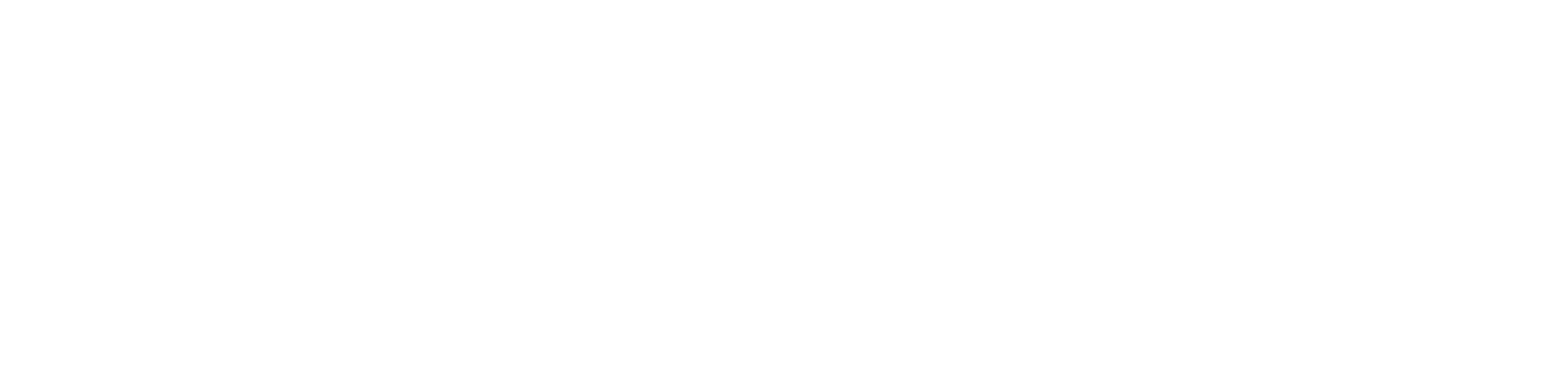

More than frozen moments in time, photographs become a window into memories of the past. Adria L. Imada, UCI history professor and author of An Archive of Skin, An Archive of Kin: Disability and Life-Making During Medical Incarceration (University of California Press, 2022), knows this phenomenon well. Her work not only bridges the gap between medicine and the humanities but also reshapes common understanding of history, one snapshot at a time.

Imada's exploration of Hawaiʻi’s leprosy outbreaks, which caused alarm in the 1860s after smallpox and measles epidemics, has earned her acclaim and prestigious awards, most recently from the Western History Association (WHA) and the Western Association of Women Historians (WAWH). Examining the longest and strictest medical incarceration practice in history that spanned over one hundred years, her research sheds light on the often-forgotten narratives of those affected by medical quarantine and public health racism.

Uncovering forgotten stories

Imada is the 2023 recipient of the Sally and Ken Owens Award, a yearly recognition by the WHA given to the best book on the history of the Pacific West region. For Imada, these accolades symbolize validation for a project that is near to her heart.

A prominent scholar in the field of medical humanities, Imada grew up in Hawaiʻi with only a vague awareness of a village on Molokai set aside for people with the now-curable illness called Hansen’s disease – more commonly known as leprosy. Stumbling onto medical examination records at the Hawaiʻi State Archives, she learned about how generations of individuals with Hansen’s disease were examined not far from her home and later sent away to die. The site of this detention facility is only a few miles away from where her grandparents lived and the elementary school her mother attended. Imada came to understand a hidden history of how Hawaiian and immigrant families in Hawaiʻi were torn apart, but also how they managed to support each other during strict medical incarceration.

Innovating with visual storytelling

Along with its depth of historical research, An Archive of Skin, An Archive of Kin is especially noteworthy for its use of photographs as a primary storytelling medium. Her strategic use of photographs as primary sources to explore the emotional, cultural and social aspects of medical incarceration also earned her the Barbara "Penny" Kanner Award from the WAWH. Examining thousands of images ranging from clinical photographs to informal family snapshots, she interprets the meanings and uses of these photographs.

“Over a period of about five years, I held and touched each of the approximately 1,400 clinical photographs one at a time,” she writes. “My encounters with these images also went beyond the visual to the tactile. Touching each photograph was an encounter with a person. It is hard not to feel moved by the collective weight of these images and the experiences of the people within.”

Imada's approach to these images was guided by ethical considerations. She candidly admits, "I struggled mightily about how I might use, publish and discuss clinical images of men, women and children from medical archives, especially ones revealing disfigurements and disabilities.” Adopting what she calls an “ethics of restraint,” she carefully selected photographs, discussing her choices with individuals close to present-day Molokai settlement residents to ensure sensitivity to survivors within these communities.

Reshaping our perception of medical history

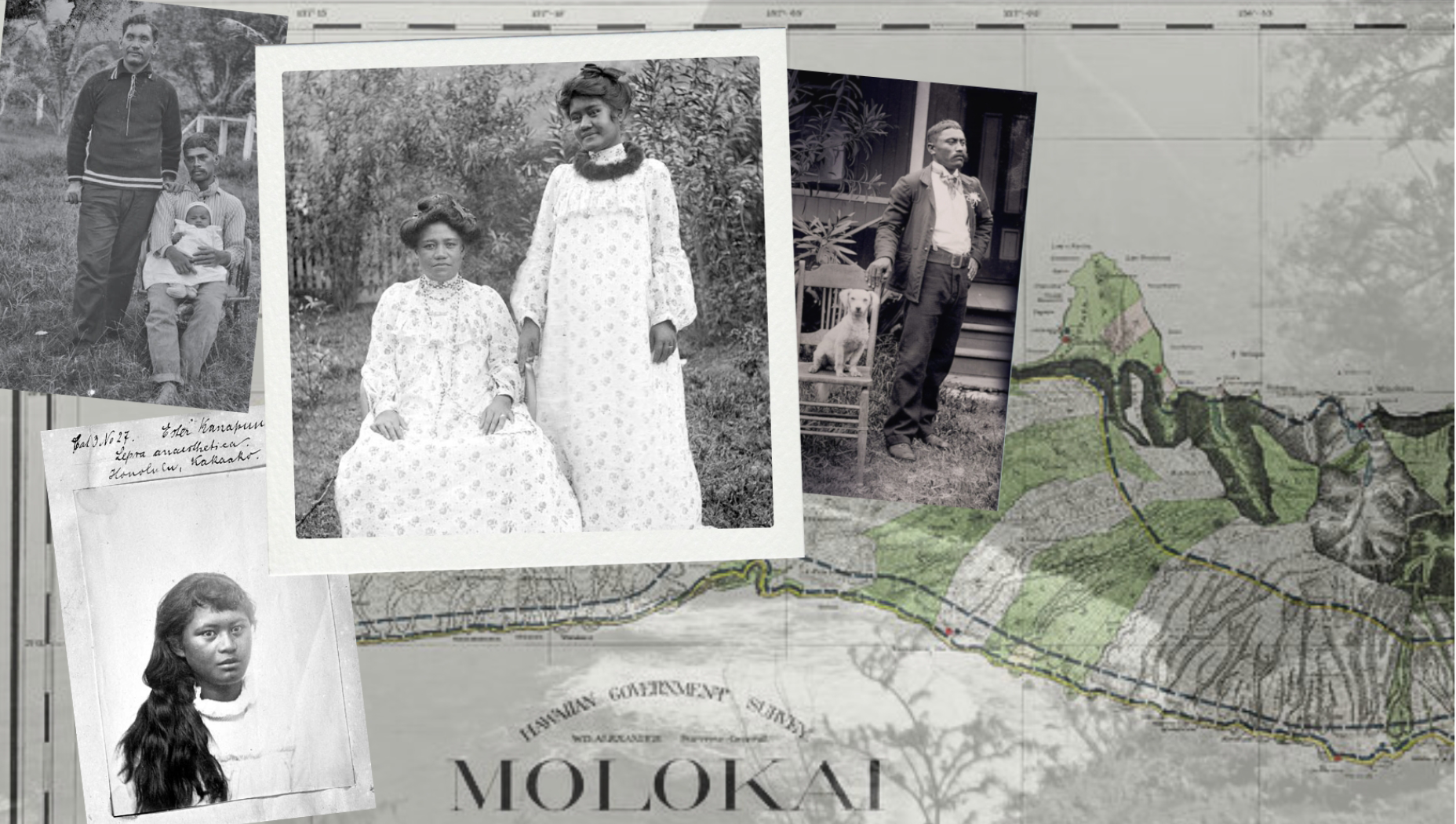

To further challenge the violence of the medical images, she worked to balance them with contrasting photographs, such as those of people posing outside of the clinic. “They dressed themselves meticulously, often presenting new family members and pets. I call these portraits and snapshots an archive of kin,” shares Imada.

She explains the archive of kin as a counter-archive; whereas the archive of skin created medical statistics, the archive of kin reveals individuals reclaiming their personhood and rebuilding communities.

The book thus offers evidence of lives interrupted by medical surveillance and incarceration. One particularly meaningful photograph to Imada, featured on the cover, is that of Naihe Pukai (sometimes called Pukai Naihe), taken in the Kalaupapa settlement around 1910. This image captures a man standing with a dog after the death of his wife and forced separation from his children. Imada reflects on its significance, stating, "The dog became his new family member in the wake of much loss. People have told me this dog reminds me of their own beloved companions, though I’m personally much more of a cat person!"

Imada advocates for recognizing the latent power embedded in these photographs. Leprosy, a disease that can visually deform the face, invited fear and revulsion from Western populations. Yet in what might be considered the greatest act of defiance, Molokai residents refused to hide away as was expected of them, instead posing alongside pets, friends, loved ones and found families in haunting and humorous photographs. A man who lived through decades of exile stands out to Imada, who explains how he joked about his condition, referring to leprosy as “leperoses” or the “handsome disease.”

As babies were born and new connections were made, the photographs became evidence of life, not death. Long after the individuals captured in these photos passed away, the images endured in archives and personal albums.

Humanities and medicine

Since Imada was not trained as a historian of medicine, she explains retooling as slow, challenging and exciting. A multi-year National Institutes of Health biomedicine grant provided her with the time and resources to do so. The grant supported her research and fieldwork at the Kalaupapa National Historical Park, National Library of Medicine and National Hansen’s Disease Museum in Carville, Louisiana, among other archives. It also encouraged collaboration with historians of medicine, physicians, medical students and disability studies scholars.

Her receipt of the WAWH’s Frances Richardson Keller-Sierra Prize, awarded for the best single-authored, original research-based monograph in the field of history, underscores the pivotal contribution of medical humanities in challenging historical narratives, particularly in healthcare practices related to disadvantaged communities.

Furthering her commitment to bridging the gap between medicine and the humanities, Imada’s current project (made possible through an Andrew Carnegie Fellowship) extends beyond Hawaiʻi to explore ordinary people surviving twentieth-century epidemics. Some of these hidden survivors, she recalls, were people with chronic illnesses and psychiatric disabilities in communities between Hawaiʻi, the U.S. South, Indian Country and the western United States. Photography was the foundation of her first two books and will have a place in her new project, but she’s currently focusing on music composed and performed by people with disabilities and chronic illnesses.

Imada’s extensive research has also influenced her teaching of the medical humanities, which are available to students as a minor and graduate emphasis. She stresses, "Clinicians really need more humanistic perspectives so they can treat the person, not just the body. My students are shocked to learn how people their age had experienced such extreme forms of settler colonial quarantine not long ago. I try to connect the dots between mistrust of medical providers and poorer health outcomes."

For those interested in learning more about the intersection of humanities and the medical field, Imada is developing a new medical humanities course for spring 2024 about everyday survivors of twentieth-century epidemics that relies on An Archive of Skin, An Archive of Kin and other communities. “Students are keen eyewitnesses to the COVID-19 pandemic, and they’ll contribute their reflections on how they managed to navigate the past three years,” she explains.

She adds, “I’m excited to teach more students between the humanities and STEM fields, especially those anticipating future work with medically underserved communities.”

This article is part of our series exploring health and medicine through the lens of the humanities. Sign up for our monthly newsletter to read more.