By Nikki Babri

In an era where digital simulations shape everything from weather forecasts to pandemic responses, UC Irvine Professor of Film and Media Studies Peter Krapp exposes a central paradox: the very technologies that shape our future are essential for maintaining access to our vanishing digital past.

Since joining UCI’s Department of Film and Media Studies in 2004, Krapp has investigated how digital technology shapes our understanding of memory and knowledge. His latest book, Computing Legacies: Digital Cultures of Simulation (MIT Press, 2024), examines simulation as more than a technological tool. Rather, it’s a fundamental way we preserve and make sense of our digital heritage.

The research for Computing Legacies emerged from Krapp’s extensive international collaborations between 2018 and 2022. As a visiting professor at Brazil’s UNISINOS São Leopoldo and senior fellow at both Germany’s Institute for Advanced Study on Media Cultures of Computer Simulation and Konstanz University, Krapp engaged in workshops and conversations that shaped the project’s interdisciplinary approach. These international partnerships, he notes, continue to influence his ongoing research into digital culture and preservation.

The evolution of simulation

The meaning of simulation has evolved significantly. Before World War II, “simulation” was associated with deception and false pretense. After the war, it became a way to copy or recreate real-world situations in controlled environments for study and training purposes. Today, it’s essential to fields ranging from pilot training to pandemic response, weather forecasting to political predictions, nuclear physics to traffic management.

As the world is increasingly mediated through digital interfaces, Krapp argues that understanding simulation has become as crucial as traditional literacy. “Simulation is a great topic for media studies. When we study the connection of knowledge and media historically, we look at symbolic systems, machines, institutions and practices that contribute to how knowledge is formed, disseminated and maintained,” says Krapp.

Today’s simulations serve three key roles in preserving and understanding digital culture: they make complex ideas clearer through vivid models; they enable new approaches to problem-solving; and they serve as archives for retaining knowledge that might otherwise be lost.

The book sets simulation alongside other essential human practices such as reading, writing and speaking – referred to by Krapp as “cultural techniques.” “Cultural techniques are symbolic practices that frame cultures and collectives through media,” he explains. Unlike basic survival activities like hunting, cooking or building shelter, these practices help societies develop forms of “hypothetical literacy,” which allow us to critically examine and preserve our understanding of the world.

Preserving our digital past

Think back to the CD-ROM, once heralded as the perfect solution for storing digital information. Protected from water damage and sunlight, these iridescent discs seemed indestructible. Yet today, many computers no longer include CD drives, which has made these so-called “permanent” archives largely unreadable. The distinctive sounds of 8-bit retro-gaming faced a similar fate – once inescapable in arcades and home consoles, they now survive primarily as nostalgic recreations and imitations.

A computer’s ability to “impersonate” another has transformed cultural preservation. Paradoxically, each new technology that promises to improve our ability to save information often accelerates its eventual obsolescence. This is where simulation and emulation become essential, offering ways to preserve not just the data, but the entire experience of using these historical technologies.

“We underestimate how quickly computing changes, which challenges our continued access to important information,” Krapp explains. “The same holds true for the history of cinema and television, of games and online interactions.”

Where simulation explores future possibilities, emulation software serves as a digital translator, allowing old programs to run on new systems. In Computing Legacies, Krapp points to a 1978 study of a U.S. insurance company that had to run seven different levels of computer emulation simultaneously just to access their data from the 1950s as they upgraded their technology. This complex workaround illustrates a fundamental challenge: while text documents and static images can be transferred between formats relatively easily, interactive media – from operating systems to video games – require more sophisticated preservation approaches.

“We see that our digital heritage is in peril of disappearing fast,” says Krapp. “Whether in education, museums, hobby preservation or professional historical scholarship, emulation can help preserve the look and feel of interactive environments even as their original hardware and software become obsolete.”

Vanishing digital records

Cultural institutions like libraries, museums and universities work to preserve knowledge and to offer means to access it. Their task has grown increasingly complex, however, as the historical record moves online through emails, texts, social media and digital archives. “A quarter of all web pages that existed at one point between 2013 and 2023 are no longer accessible,” Krapp reveals, “and over half of all Wikipedia pages have at least one link in their ‘References’ section pointing to a page that no longer exists.” Similarly, according to Krapp, 90% of tweets are unavailable within six weeks.

Though some digital loss is to be expected, the challenge to preserve these histories is compounded by two factors: widespread defunding of cultural institutions and a deceptive sense of digital permanence. The apparent ease of copying and storing digital information creates an illusion of abundance, while important data continues to slip through the cracks.

The recent “banning” of TikTok, which resulted in the site becoming unavailable for its 170 million American users for 12 hours, is a particularly stark example of how quickly a segment of our digital history might disappear.

The future of digital interaction

Drawing on centuries of educational history, from Francis Bacon’s 17th-century model of college education to contemporary online learning platforms, Krapp challenges popular narratives about technological solutions in education, particularly those promoting massive online classes as replacements for traditional learning environments.

Unlike real estate, where a decade-old house might maintain its relative value, a ten-year-old computer quickly becomes out-of-date. In education, this rapid evolution demands constant updates and innovations in curriculum development, making quality education an ongoing investment rather than a one-time solution.

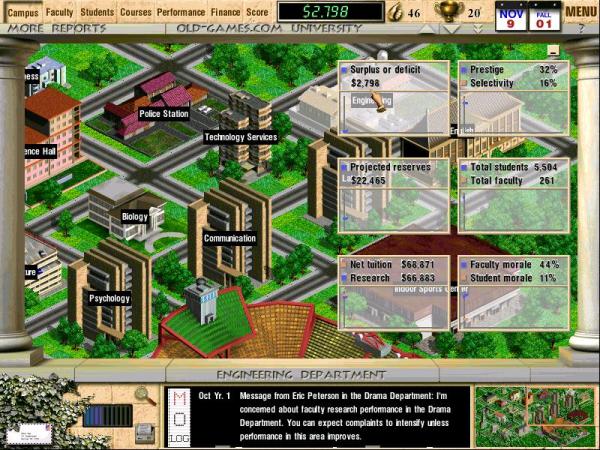

Early educational simulations like Owen Gaede’s 1975 program Tenure, which simulated a teacher’s first year, and the simulation Virtual U in 1999, which let players manage a university, promised to revolutionize higher education through gamification. However, Krapp points out that despite the allure of these interactive tools, they often follow a familiar pattern of declining quality that prioritize scale over substance – a phenomenon one colleague colorfully calls the “enshittification” of online interactions.

While Krapp’s work engages with rapidly evolving technology, he maintains a measured perspective on technological progress. “Contrary to the dubious consolations of simple timelines, media culture is recursive and self-reflexive,” he asserts. He pushes back against sensationalized views promoted by prominent figures like Jean Baudrillard, Neil deGrasse Tyson and Elon Musk, cautioning against oversimplified arguments that suggest we’re already living in a computer simulation simply because of advances in graphics technology.

Ultimately, Krapp argues, successful digital preservation requires more than just technical expertise. “Simulations would be incomprehensible if they were just restricted to symbols or numbers – so they are still about storytelling, which is, of course, the humanities’ domain,” he writes. By bringing together technical innovation and humanistic interpretation, Krapp offers a framework for understanding and preserving our increasingly complex digital heritage.

Follow Krapp's Instagram @secretcommunications for exclusive photos and commentary related to Computing Legacies.

Interested in reading more from the School of Humanities? Sign up for our monthly newsletter.