By Nikki Babri

Words carry immense weight, especially in the narrative of Palestine and Israel, where every word bears the burden of history. In her new book, Conflicts: The Poetics and Politics of Palestine-Israel (Fordham University Press, 2024), Liron Mor, associate professor of comparative literature, discusses the gravity of words, focusing on a term often accepted without scrutiny: “conflict.”

Mor's distinctive approach blends political and rhetorical theory with a comparative study of Hebrew and Arabic literature. This interdisciplinary lens challenges the traditional separation between the conceptual and the poetic, the universal and the local. Mor’s literary archive spans from the 1930s to the present, incorporating works from recognized writers to lesser known contemporary voices in prose, poetry, film and television. Her scholarly background complements this approach. She explores juridical and political mechanisms in Palestine-Israel, Mizrahi Jewish cultures and indigenous forms of knowledge and resistance. At UCI, she teaches seminars on Hebrew and Arabic literature, as well as courses on broader topics like terror, Orientalism, refugees and detention.

Mor challenges the foundational nature of the term “conflict” in this context, recognizing it as neither an objective nor neutral concept: “It is nearly impossible to find an English-language discussion of Palestine-Israel that does not invoke the term ‘conflict.’” Her book Conflicts is dedicated to reexamining this central political paradigm, arguing that what takes place in Palestine-Israel is not a “conflict” and that this context defies conventional definitions.

She begins with three fundamental axioms that challenge the widely conventional construct of the “Israeli-Palestinian conflict”: 1. It does not take place between two parties. 2. It is not separate from its literatures. 3. It is not, in fact, a conflict.

Recognizing the significance of language, Mor deliberately uses “Palestine-Israel” to designate the region discussed, acknowledging its historical and geographical entanglements. However, she shifts the emphasis to the literatures involved and refers to “Arabic” and “Hebrew” whenever possible. Literature and cultural artifacts, she argues, offer local, more nuanced frameworks for understanding the political landscape.

In seeking other political prisms to replace “conflict,” Mor finds existing political terms – such as colonialism, settler colonialism, occupation, apartheid and siege – to be insufficient. While useful in reflecting different Israeli methods of oppression, these mostly imported, partial frames neglect Palestinian experiences and perspectives. Instead, she introduces alternative concepts like levaṭim (disorienting dilemmas), ikhtifāʾ (anti/colonial disappearance), ḥoḳ (mediating law) and inqisām (hostile severance), which are all drawn from the rich literary archive.

A historically neglected narrative

For Mor, the political is personal. “Most of my family originated from the Arab and Muslim world,” she shares. She is the daughter of a Kurdish Iraqi father and a half Algerian mother. Her father’s family, along with nearly all Iraqi Jews, was forcefully removed from Iraq in 1951, a year known as “Sant al-Tasqit.” Upon arrival in Israel, they found themselves living in a “transitional camp” (ma’abara). She recounts that, upon marriage, her mother rushed to relinquish her Algerian maiden name, Ayache, which means “full of life” in Arabic. This small slice of Mor’s family history mirrors the discrimination faced in Israel by Mizrahi (“Eastern” in Hebrew) Jews – those from the Arab and Muslim world – who were met with inequalities in resource allocation and political representation, as well as displacement and dispossession.

“Their cultures, too, have been marginalized – so much so that there was shame in my mother’s Arabic surname,” Mor explains. “Hegemonic Israel thought of itself as saving Mizrahi Jews from ‘primitive’ lives in the Arab world saturated with violence, but often Mizrahi Jews were urban and highly educated. They enjoyed much better, more peaceful relationships with their Muslim and Christian neighbors than Jews in Europe did.”

Growing up Mizrahi in an Israeli border town, Mor experienced the question of violence in the region firsthand. Intermittent rocket fire and stories of guerilla invasions made this question a tangible reality. Her later move to Jerusalem during the Second Intifada intensified this sense of urgency, exposing her to Palestinians, their personal stories and the routine violence inflicted upon them.

“Sensing that there was something embarrassing or ‘less than’ in my heritage raised questions for me. What was it about Mizrahi Jews’ Arab or Middle Eastern background that was so scary, shameful or distasteful that it had to be erased?” she asks. “Was it their ‘Arabness’? Their ‘Easternness’? Was the problem that these made them too similar to the Palestinian ‘enemy’? Or was it rather that these made them too similar to ‘exilic Jews,’ whose perception by Europeans was historically refracted through the antisemitic tropes of the ‘Oriental Jew?'”

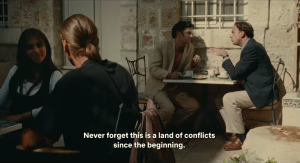

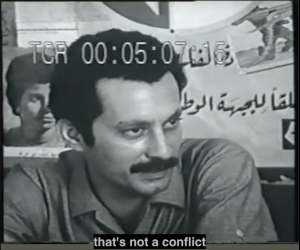

These questions spurred Mor’s curiosity about the assumed age-old animosity between Jews and Arabs. She was encouraged by events and advisors to rethink the seemingly inherent and unquestioned nature of basic political terms. Drawing inspiration from a 1970 interview with Ghassan Kanafani, a Palestinian revolutionary novelist, she decided to focus specifically on conflict. “Conflict is such a central term in politics, and particularly in the Palestinian-Israeli context,” she says, “that I felt compelled to dig deeper into it and try to unearth what it means, how it frames reality, what effects it might have and who it might be serving.”

Challenging symmetry

Emphasizing the figure of the Mizrahi Jew, Mor challenges the duality and presumed symmetry of the “conflict” framework. This framework, she argues, misleadingly implies an equivalent, zero-sum competition between the Israeli colonizers and the Palestinian colonized. She further grapples with the complex status of Mizrahi Jews as both colonizers and victims of displacement.

“My grandfather, like many other Iraqi Jews of his generation, did not want to leave Iraq. In order to push the Jewish community out of Iraq, Israel had to resort to shady deals with the Iraqi government and to heavy pressures to make the city appear unsafe,” she explains. “This is where the symmetry argument crumbles, for it was in fact the same cause, the Zionist regime in then nascent Israel, that was largely responsible for both displacements, of Palestinians from Palestine and of Mizrahi Jews from the Arab world.”

The book calls for a triangulation, considering the involvement not just of Jews and Arabs, but of European and non-European Jews, various Palestinian groups (exiled Palestinians, Palestinians within 1948-borders Israel who are its citizens and those in the Occupied Territories) and, crucially, European imperialism.

Addressing current events

As is often the case in research that addresses the contemporary, Mor faces the challenge of navigating dynamic changes on the ground, particularly with events occurring after the completion of her book. While she was able to touch on the 2023 “judicial reform” (or “judicial coup”) during proofreading, the most recent tragic events involving Hamas’s attack in Southern Israel on October 7th and Israel’s massive military response in Gaza could not be addressed in the book.

Mor reflects on these events, suggesting that, despite their unprecedented, devastating results and scale, they fit with the former conceptual frameworks she traces in the book. “For instance, you could easily see how the false symmetry of the concept of 'conflict’ resonates these days, when we regularly hear about the ‘Israel-Hamas war’ or the ‘Israel-Gaza war,’ as though we are witnessing a military conflict between two equal sides who are fighting on a level playing field and under the same terms,” Mor says. She explains that in this sense, the concept of conflict is deeply misleading. It paints a colonizing people, with huge military and technological might, and a colonized people – suffering from varying degrees of siege, apartheid, war and occupation – as symmetrical parties vying over a single strip of land.

“If I could change the book, I would have likely drawn out these continuities and connections with the present explicitly,” she comments. “Two of my alternative frameworks are especially useful in understanding what is taking place right now. The first is the concept of inqisām (‘split’ or ‘severance’), which conceptualizes the internal splitting of the population as a mode of control. The second is the concept of ikhtifa’ (‘disappearance’), a prism for understanding settler colonialism in Palestine and the Zionist psychology that allows it to continue. It accounts for the erasure of the Palestinian identity and for the blindness of Israelis to the effects of their actions.”

Mor’s hope is that the book brings people the knowledge and understanding they seek, especially in this time of great confusion. “Perhaps more importantly, I hope that it makes people realize that more knowledge and understanding need to be sought,” she says. “That it helps people sense that we all do not know as much as we think we do and that our very conviction that we know, or that we know enough, is central to the problem. Hopefully, some of the alternative frameworks I offer serve as a constructive starting point.”

Interested in reading more from the School of Humanities? Sign up for our monthly newsletter.