Part I, Pledging Allegiance - 00:37; Part II, The Cold War Comes to UC - 15:39; Part III, The California Loyalty Oath Crisis in Three Acts - 25:12; Part IV, Lessons from the History of Academic Freedom - 44:47

[Though lengthier than a newsletter article, what follows is not a scholarly study but a personal reflective essay I am sharing to inform my readers about an historical episode in the life of the University of California and to occasion further reflection on the issues this episode raises. And though I am indebted to a number of primary and secondary sources in what I have written, I have foregone any formal apparatus of footnotes and citations. I have tried, where possible, to indicate my derivations in the body of the text, and I provide at the end, not anything like a comprehensive bibliography, but a list of selected works from among those that I consulted in writing this piece and that may be of interest to some readers for further investigation of the topics discussed here. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not represent those of the Regents of the University of California, the UC Irvine campus, or the UC Irvine School of Humanities.—TM]

I. Pledging Allegiance

When I became an employee of the University of California as a new associate professor at UC Santa Cruz in 1999, I, like all public employees of the state except for those who are non-U.S. citizens, was required to sign the “state oath of allegiance.” Stipulated in the California Constitution, this oath reads in full:

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of

the United States States and the Constitution of the State of California against all

enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the

Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the State of California;

that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of

evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties upon which I am

about to enter.

The signed affirmation of this oath, to be taken before an employee authorized to witness it, is part of the regular “on-boarding” process for new university employees. I would venture that in its current mode of delivery, this oath-taking leaves little impression on most signers, who after a short time, I suspect, don’t even recall that any such thing has been required of them. Just one more form in a thick stack to sign before the first day of work, from benefits designations to payroll information to direct deposit account numbers, our solemnly sworn oath languishes until further notice in a digital file in university Human Resources. On several campuses—including at UC Berkeley and UCLA, which figure prominently in the historical oath controversy I will discuss—the state oath of allegiance is conveniently combined with the longer, more detailed acknowledgement of the University of California’s property rights when patents and licenses arise from an employee’s work using the university’s resources and facilities.

If today the taking of the state oath of allegiance has been routinized and streamlined to the point of near-oblivion, this was emphatically not the case seventy-five years ago, in the early years of the Cold War. During the so-called “Year of the Oath” and its aftermath, in the period from March 1949, when an extended, explicitly anti-communist “loyalty oath” was proposed by UC President Robert W. Sproul and adopted by the UC Regents, to August of the following year, when the Regents of the UC dismissed thirty-one Senate faculty members for their refusal to sign it, the loyalty oath was a matter of fiery university debate and public uproar. It had profound consequences for the individuals involved, along with the reputation of the University of California. During several intense months of conflict, key matters of academic freedom, faculty tenure, and the governance of the university (with several sensitive questions of civil liberties as well) were put to the test and heatedly discussed by the Regents, Academic Senate leadership, faculty and students, alumni, and the press.

It is worth recalling here that in the days of the oath crisis, the University of California looked quite different from how it does today. Rather than today’s relatively autonomous individual campuses, each with their chancellors and provosts, the system still had no chancellors and was more directly led by its President. There were Provosts on the Berkeley and Los Angeles campuses who reported to the President, and the Academic Senate was divided into just two branches, a northern and southern section. Also, although in various official and customary ways the University of California had for a long time recognized the basic principles of academic tenure—the offer of continuous appointment after a lengthy provisional term in which a professor’s teaching and research has been judged worthy of such high recognition—in fact, as the situation of the oath revealed, the Senate faculty’s right to tenure was weakly codified and hence vulnerable to public pressure and to the political maneuvers of trustees such as Regent John Francis Neylan and his allies on the governing board. Though typically the UC Senate faculty had received an annual letter stating that they would receive such-and-such salary for their appointment in the coming year, without mention that this was a “renewal” of their appointment, the requirement of the loyalty oath revealed that the Regents could effectively consider even the tenured faculty of the university annually appointed employees, subject to termination or non-renewal.

The institution of tenure, thus, heralded as one of the strongest protections for the faculty’s academic freedom of research and instruction, was thrown in serious doubt by the seemingly trivial introduction of a new paragraph in the constitutional oath disavowing communism, a political ideology which, despite the suspicions of a few Regents, had virtually no support from the UC faculty in the first place. Indeed, as would be highlighted during the oath year, the UC had already for years by policy forbidden the appointment of communists in 1940, on the grounds that membership in the Community Party contradicted, by definition, the objective teaching and pursuit of truth expected of UC professors. (Notably, decades later, the UC Regents were still appealing to this policy in the first firing of Angela Davis, an acknowledged member of the Communist Party, from her acting appointment in philosophy at UCLA in 1969, a dismissal which was overruled in California Superior Court as unconstitutional.) Most professors at the time of the loyalty oath crisis, in fact, accepted the anti-communist premise of the policy, while a minority, who believed that a communist might still be an objective teacher and researcher, had quietly acquiesced in it. It is worth underscoring too that throughout the crisis, which culminated in the firing of the remaining thirty-one faculty non-signers, never was there any evidence that the University’s faculty were members of the Communist Party, supporters of it, or advocates of the violent overthrow of the government. In fact, as Bob Blauner notes in his book on the crisis, “The University of California… was a conservative institution, despite its façade of enlightened liberalism.” But it had a strong tradition of faculty Senate co-governance, which set up the loyalty oath to become a flashpoint of contention, a matter in which questions of faculty voice in governance, academic freedom, and related responsibilities in appointment, tenure, evaluation, and administration of due process for faculty were acutely raised.

Former UC President Clark Kerr writes in his memoir The Blue and the Gold, that “The issue was never only communism…. What was really at issue was that the regents seemed to identify the members of the faculty as particularly suspect among all citizens of the state.” Yet it is not clear how genuine that suspicion even was, or whether, at least in the course of events, an originally ideological premise had not evaporated into a sheer power struggle over the governance of the university itself, with some Regents wanting to make an example of a group of faculty who persisted in challenging their authority over what the faculty saw as their rightful purview. In the Regents meeting of July 21, 1950 that led to a slim majority vote to dismiss, Regent Cornelius Haggerty, arguing for retention, said with exasperation, “Now I learn we aren’t talking about Communism…. There is no longer an impugning of those individuals as Communists. It is now a matter of demanding obedience to the law of the Regents.” His fellow Regent Arthur McFadden, on the other side of the vote, admitted, “No Regent has ever accused a member of the faculty of being a Communist.” The presiding judge, Annette Adams, in the 1951 court case challenging the dismissals was even more pointed in stating the stakes of the Regents’ action. When the Regents’ counsel Eugene Prince stated explicitly that there was no question of the dismissed faculty’s individual loyalty, she responded: “The issue, then, is that they were naughty boys and girls because they didn’t obey the teacher and sign.”

It is notable that the loyalty oath crisis in various ways engaged several key leaders in the University of California in its wake. Clark Kerr, unquestionably the best-known UC President of any, was not himself a non-signer at the Berkeley campus. During the Year of the Oath, however, he was supportive of the non-signers and served on the northern Academic Senate’s Committee on Privilege and Tenure, which sought, unsuccessfully, to intervene at a decisive moment in the crisis. In the immediate wake of the firings, Kerr became the first Chancellor of UC Berkeley and eventually the UC President, and presided over various measures that more firmly codified tenure rights and helped repair the damage that the loyalty oath affair had wrought on the university’s reputation nationally. David Saxon, a professor of physics at UCLA who was fired for his refusal to sign and reinstated after court action in 1952, went on to become President of the UC from 1975 to 1983. David Gardner, who as a young professor at UC Santa Barbara wrote the first history of the loyalty oath crisis, followed Saxon as UC President, serving from 1983 to 1991. Though subsequent presidents have not been as directly connected with the specific history of the loyalty oath, it remains notable that academic freedom has been an important question for more recent presidents as well. President Richard Atkinson (1995-2003), for example, oversaw a major overhaul of the UC’s policies on academic freedom, while President Mark Yudof (2008-2013), a scholar of law, has authored widely-referenced studies of constitutional and other legal aspects of academic freedom.

The matter of the Cold War loyalty oath has, by now, been consigned to ancient history in the University of California, a matter of interest primarily for archivists and specialized historians. I am no longer surprised that very few of the colleagues to whom I mentioned the topic of my summer reading are even aware that this episode took place in our institution. In 1999, right before the 20th century disappeared definitively from our calendars and from the day-to-day parts of our minds, the Berkeley campus hosted a symposium on the 50th anniversary of the oath controversy. Kicked off by Chancellor Robert Berdahl with a panel discussion of the former UC Presidents Clark Kerr, David Saxon, and David Gardner, it also included presentations by several other surviving participants of the events of 1949-50, and an exhibition in the lobby of the campus’s signature campanile tower. This is how universities typically lay painful matters of the past to rest: with sober, measured rituals of remembrance, laced, perhaps, with judicious doses of wisdom to put in store against an uncertain future.

Recent events in the university and nationally, however, may make us wonder how peacefully the ghost of UCs-past may be sleeping. Signs and prodigies emanating from state houses around the country and from Washington might indicate otherwise. For example, the Presidential Executive Order of August 7, 2025, “Improving Federal Oversight of Grantmaking,” stipulates that the award “must, where applicable, demonstrably advance the President’s policy priorities,” blurring the line between national scientific priorities and personal, partisan ones of the chief executive. It disallows discretionary awards—i.e. grants—"to fund, promote, encourage, subsidize, or facilitate” not only racial preferences or illegal immigration, but also scientifically well-founded questioning of “the sex binary in humans,” and warns against “any other initiatives that compromise public safety or promote anti-American values.” This last undefined and indefinitely expandable bag of “bads”—we can only guess what might ultimately come to be included in it—brings us only one short step away from the return of obligatory professions of loyalty, the sworn disavowal of any intention to promote anti-American values, that once pervaded the American professions in the 1950s.

II. The Cold War Comes to UC

The California Loyalty Oath controversy is often seen as an exemplary episode in the nationwide history of “McCarthyism,” though in many ways it was in the advance-guard of the wave of anti-communist hysteria and attacks on civil liberties that has come to be associated with the name of Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin. Well before McCarthy became a U.S. Senator in 1947, the U.S. House of Representatives in 1938—in a different wing of the Capitol—had constituted the House Committee on Un-American Activities, which in 1946 became a standing committee. California State Senator Jack Tenney followed suit at the state level, heading the notorious Tenney Committee, a "little HUAC,” from 1941 to 1949. Originally founded with the intention to combat communism, the Tenney Committee took up a side project and helped institute the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II before turning its attention back to rooting out communist subversion following the end of hostilities. It is generally known that Jim Corley, the University Comptroller and authorized representative of the University, periodically consulted with Tenney about the UC and the putative dangers of communist subversion within it, and that UC President Sproul’s proposed loyalty oath may have been spurred by Corley’s advice to try to stave off more direct legislative intervention into the affairs of the university.

We should recall the pervasive atmosphere of fear that current events had aroused during the years leading up to and continuing into the loyalty oath affair in California. In March 1946, Winston Churchill delivered his famous “Iron Curtain” speech, often seen as the inaugural address of the Cold War. Less well-known, though perhaps of symbolic importance for later events, is that this speech took place at Westminster College, a small institution of higher education in Fulton, Missouri, where Churchill was accompanied by President Harry S. Truman. After World War II, communist insurgencies and communist-supported national liberation struggles had in fact arisen in many countries throughout the world, while in Eastern Europe the consolidation of Stalinist dictatorships was advancing under the watchful eyes of the occupying Soviet army. Most distressingly, in 1949 Mao Zedong’s Chinese Red Army achieved victory over the nationalist forces on the Chinese mainland, who fled to the island of Taiwan. Soon after (and nearly at the peak of the California loyalty oath controversy), South Korea was invaded by the North Korean army, leading the United States to send ground troops to the Korean peninsula in support of the South. High-profile trials of accused communist spies such as Alger Hiss in 1949-50 and Klaus Fuchs in 1950 (in Great Britain, though he had worked in the United States) and the arrest of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in 1950 (executed in 1953) contributed to fears that communists had deeply infiltrated into government and scientific institutions and were set to betray atomic and other dangerous secrets to the Soviets.

This anxious climate encouraged the widespread imposition of loyalty oaths on as many as one in five employees during the 1950s, and led to purges of leftists from unions and other organizations, surveillance of activists, and blacklisting. Though it was fortunately never implemented, in a letter from F.B.I. director J. Edgar Hoover to a presidential consultant for Truman, a plan was outlined to be referred to the President in the case of an emergency such as an attack, invasion, or rebellion. Hoover went on to note that a master list of “potentially dangerous” individuals had already been registered in an index that included about twelve thousand names, ninety-three percent of whom were U.S. citizens and the rest “aliens.” A master warrant for their detention was included in the plan, which could be rapidly activated upon declaration of an emergency. Although the proclamation, Hoover notes, would have to be approved by Congress, he seems to have felt that was a mere formality and would readily be granted. The proclamation “suspends the Writ of Habeas Corpus for apprehensions made pursuant to it”—Habeas Corpus being the constitutionally guaranteed right to appear in court and challenge the grounds of one’s incarceration—and “the plan does not distinguish between aliens and citizens and both are included in its purview.”

The terms “witch hunt” and “heresy” were never far from the debate about the loyalty oath, whether explicitly, as in California historian and editor of The Nation Carey McWilliams’ 1950 book Witch Hunt: The Revival of Heresy or more tacitly, as in non-signer Erik Erikson’s letter to the American Psychoanalytic Association, disseminated in 1951 by the journal Psychiatry:

My field includes the study of “hysteria,” private and public, in “personality” and

“culture.” It includes the study of the tremendous waste in human energy which

proceeds from irrational fear and from the irrational gestures which are part of what

we call “history.” I would find it difficult to ask my subject of investigation (people)

and my students to work with me, if I were to participate without protest in a vague,

fearful, and somewhat vindictive gesture devised to ban an evil in some magic way.

Even during the oath controversy, faculty and graduate students were quietly leaving or accepting appointments elsewhere, and the dismissals and departures led to cancellations of classes and the weakening of curricula in disciplines where non-signers were concentrated.

Even more damaging was the loss in stature and reputation of the university. Prominent faculty fired in 1950 included the medieval historian Ernst Kantorowicz, who was eagerly snatched up by Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Studies, through the initiative of the historian Theodor Mommsen and art historian Erwin Panofsky and with the support of the Institute’s director Robert Oppenheimer; the psychologists Edward Tolman, who was reinstated only after a successful suit against the Regents, and Erik Erikson, who left for the Austin Riggs Center in Massachusetts and eventually to Harvard; and physicists Wolfgang Panofsky and Gian Carlo Wick, who took up professorships at Stanford and Carnegie Mellon respectively. Internationally renowned faculty who had been offered positions or invited to visit or speak at Berkeley and UCLA turned them down in the wake of the firings. These included, for example, the writer and literary critic Robert Penn Warren from Yale University, physicist Edward Teller and philosopher Rudolf Carnap from the University of Chicago, the sociologists Robert Merton and Paul Lazarsfeld from Columbia University, and the landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, among others.

The UC earned widespread condemnation from professional organizations and from leaders of other universities, as well as formal censure from the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), which for decades had striven to establish and protect academic freedom in American universities. As the Chancellor of UC Berkeley and future UC President Clark Kerr later wrote, a serious question among the leaders of the top research universities in the United States was “Who Will Take Berkeley’s Place in the Academic Big Six?” after the loyalty oath crisis. Kerr’s most urgent task as Chancellor, he acknowledged, was to ensure that the answer would be “No one.”

III. The California Loyalty Oath Crisis in Three Acts

The California loyalty oath, which occasioned so much mischief, was, in fact, not just one thing, but a series of successive revisions and reconfigurations. That is because a flawed proposal was introduced at the very beginning over the misgivings and objections of several Regents and was reworked or recontextualized several times to reflect the tactical twists and turns of the affair. Shortly after the oath’s adoption in its original form, for example, it was tweaked to refocus it more explicitly and more narrowly on membership in or support for the Communist Party (which throughout the controversy, it bears noting, remained a legal political party in the United States).

One part of the oath was not, in fact, new at all. The draft loyalty oath incorporated the already existing constitutional oath—pledging fidelity to the Constitutions of the United States and the State of California—that was stipulated by the California Constitution for all holders of public office. A side controversy arose among the Regents about whether professors of the UC were, in fact, to be understood as custodians of public office like legislators or judges, or whether they were merely “employees,” like janitors and gardeners, and hence whether the state’s constitutional requirements referred to them. In any case, the original version of the new oath adopted by the Regents on March 25, 1949, at the outset of a year of tumultuous events, read (with the new addition to the constitutional oath highlighted):

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support the Constitution of the United

States and the Constitution of the State of California, and that I will faithfully

discharge the duties of my office according to the best of my ability; that I do

not believe in, and I am not a member of, nor do I support any party or organization

that believes in, advocates, or teaches the overthrow of the United States Government,

by force or by any illegal or unconstitutional methods.

The oath, the Regents affirmed, would have to be signed before the new annual contract could be approved and the appointment renewed. A few months later, on June 25, 1949, the Regents tied the oath to an appointment policy already on the UC books since 1940, that communists could not be employed by the university. They now emended the part of the oath that followed the constitutional oath to read: “I am not a member of the Communist Party or under any oath, or a party to any agreement, or under any commitment that is in conflict with my obligation under this oath.”

President Sproul introduced the original expanded oath without prior consultation with the UC faculty. He also offered explicit assurance to skeptical Regents—which initially included even Regent John Francis Neylan, who would become the hardest-core advocate of forcing it upon the faculty—that the faculty would accept it. He also, in June, assured the Regents that the faculty would accept the freshly emended oath that explicitly calls out membership in the Communist Party, despite the lack of any evidence that his own faculty advisory committee had in fact so advised him. Sproul, who was not himself an academic but was generally held in high regard by the faculty, in this instance badly misjudged faculty ethos. When later asked by Regent Neylan why “in the name of God” the President hadn’t spoken to the faculty before introducing the offensive oath, Sproul responded candidly that he didn’t think they would have any objections. Further compounding matters by raising suspicions of surreptitious maneuvers, Sproul failed to inform the faculty of its adoption for several weeks, so that the summer recess was nearing and the Academic Senate had little time to respond. Evidence suggests this may have been an unfortunate bureaucratic lapse rather than an ill-intentioned tactic to hoodwink the faculty, but no matter, further damage had been done. When news of the oath began to trickle out over several weeks, and eventually the text to be signed by faculty before their contract could be renewed was known to all, faculty responded with perplexity, distrust, and outrage, which would only intensify with subsequent events. The controversy started to air in public as well in June 1949, when the San Francisco Chronicle first put the oath in print.

The subsequent unfolding of the loyalty oath controversy is multifaceted, and full of dubious tactics and unfortunate reactions among the principals, which made it nearly impossible for them to reach any less damaging outcome in the end, despite various attempts by faculty, dissenting Regents, and alumni to offer honorable off-ramps that would have preserved the integrity of the university. I can recount here only the barest outline of the controversy, to which its two main historians, David Gardner and Bob Blauner, have each devoted richly documented books, while, at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft library, the primary documents and oral histories related to the events span thousands of pages. I will highlight just three key turning-points around which events pivoted, leading eventually to the dismissal of the last non-signers. In his book, Blauner, taking a more emphatically faculty-centered perspective than the even-handed “inside baseball” account of Gardner, characterizes these turning points, in chapter headings, as “The Faculty Resists Sproul’s Oath,” “The ‘Sign or Get Out’ Ultimatum,” and “From the Great Double Cross to the Alumni Compromise.”

The first of these was the immediate response to the new oath in June 1949, when it was discussed both in the Academic Senate and in broader forums of students, non-Senate employees, and the public. The response was quieter and less organized at UCLA, but at Berkeley more than half of the professoriate showed up for an Academic Senate meeting on June 14, where the oath was debated and a motion was put forth for its deletion. The most spectacular and unexpected event of the meeting was the passionately oppositional address by the medieval historian Ernst Kantorowicz, whose political background in pre-Nazi Germany was in fact on the far right, as a member of the anti-socialist Freikorps militia and as part of poet Stefan George’s intellectual circle advocating for an esoteric, mythic “Secret Germany.” Very much the type of professor that historian Fritz Ringer described as the “German mandarin,” aloofly elitist, formidably erudite, and a dandyish bisexual to boot, Kantorowicz had refused to take the Nazi loyalty oath and lost his appointment at the University of Frankfurt. A Jew with a complicated identity, he fled Hitler’s Germany after Kristallnacht to escape persecution.

Kantorowicz published an account of the controversy called The Fundamental Issue following his dismissal in 1950, including key documents and notes, which earned him the rage of Regent Neylan, who accused him and other intransigents of conducting a “campaign of terror” against him and his Regent allies. Kantorowicz’s address to the Senate, which makes four basic points, was reprinted in his pamphlet. First, he argued, history demonstrates that oaths rarely remain fixed, but instead predictably accrete new clauses carrying new obligations—a point that would patently be borne out only a few days later by the revisions the Regents would soon make to Sproul’s original proposal. “A new word will be added,” Kantorowicz noted, “A short phrase, seemingly insignificant, will be smuggled in. The next step may be an inconspicuous change in the tense, from present to past, or from past to future. The consequences of a new oath are unpredictable.” Second, he argued that a seemingly harmless and uncontroversial oath is bait for additional conditions and concerns that are hard to resist or reverse once an oath is pronounced. Third, he argued that an oath that tyrannically presents the faculty with an either-or, ultimately reduced to “sign or lose your livelihood,” offends the scholarly conscience. And lastly—the most intellectually interesting of Kantorowicz’s points, since it derives explicitly from his study of medieval society—the oath offends against the very dignity of the office of the scholar, which he stresses is not a matter of “political expediency or academic freedom,” nor even about the economic coercion involved, but an even more fundamental failure to recognize the “inner sovereignty” of the “three professions which are entitled to wear a gown: the judge, the priest, the scholar.” Kantorowicz himself took the position of firm resistance to the oath and never wavered, up to his dismissal. Interestingly, a short time later, he published a scholarly article on the oaths that new medieval bishops and kings swore to the inalienable unity of the papacy and “Crown,” recognizing an obligation to an impersonal “office” rather than personal loyalty to a lord as had been the case under feudalism. There is little question that Kantorowicz viewed the California loyalty oath through the anachronistic lens of medieval thought about responsibilities of office. But might it be, as well, that his erudite scholarship in medieval history took on new acuity from his experience of the harms a badly conceived, latter-day oath could inflict?

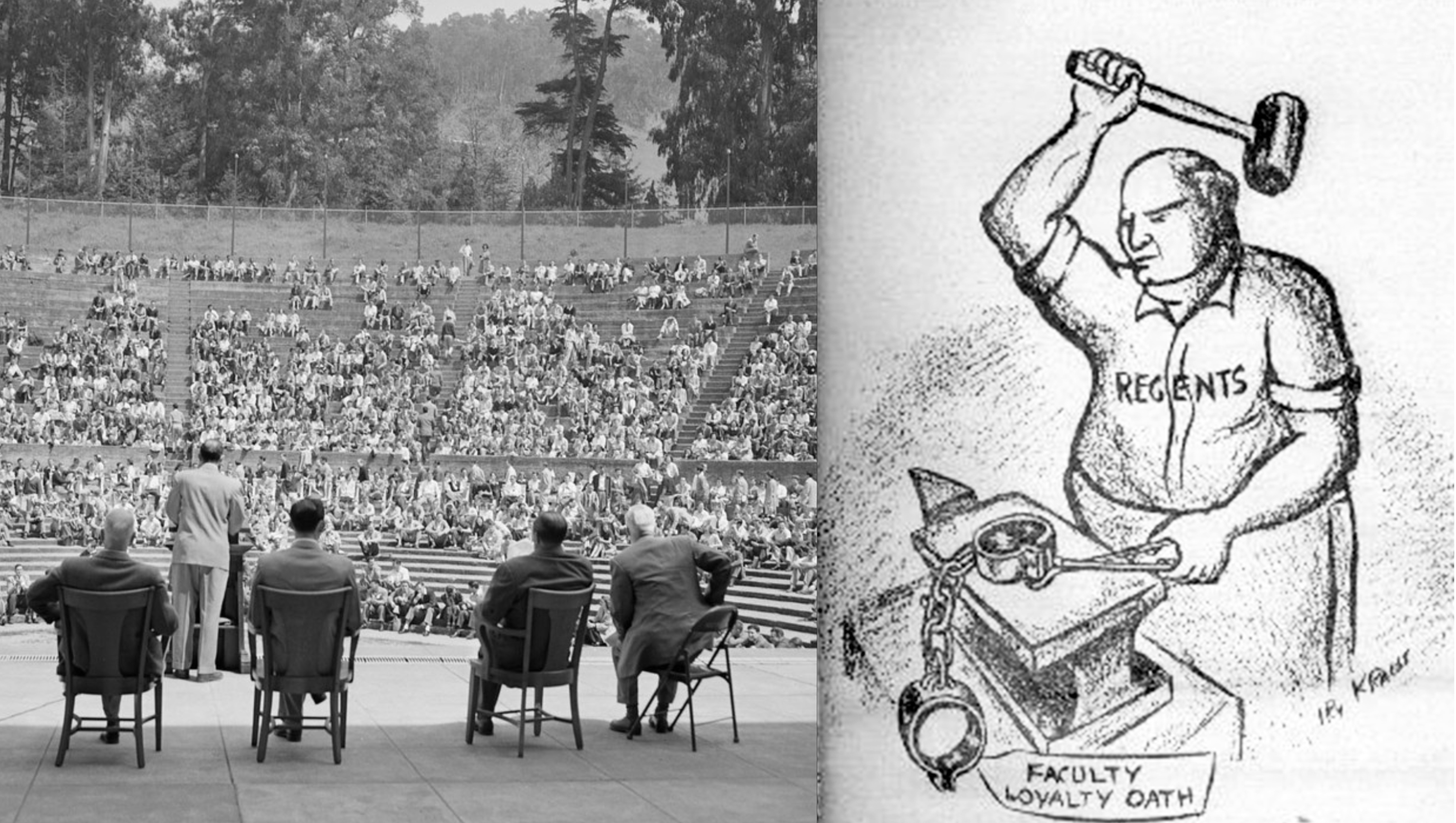

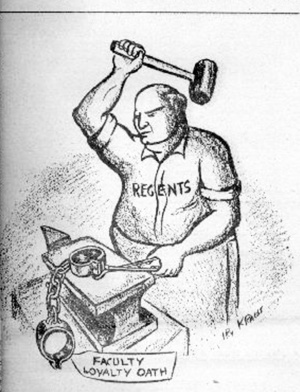

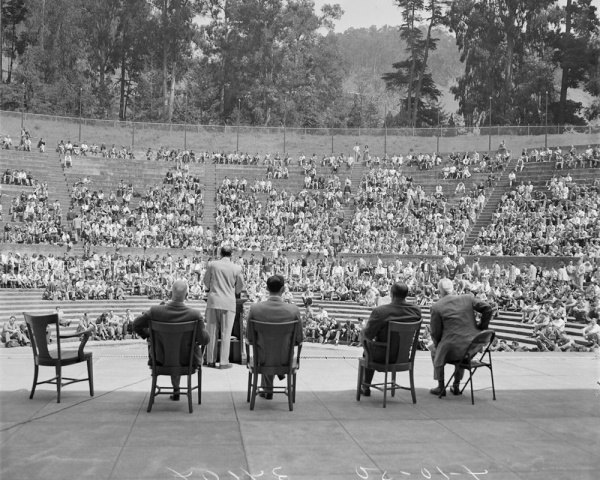

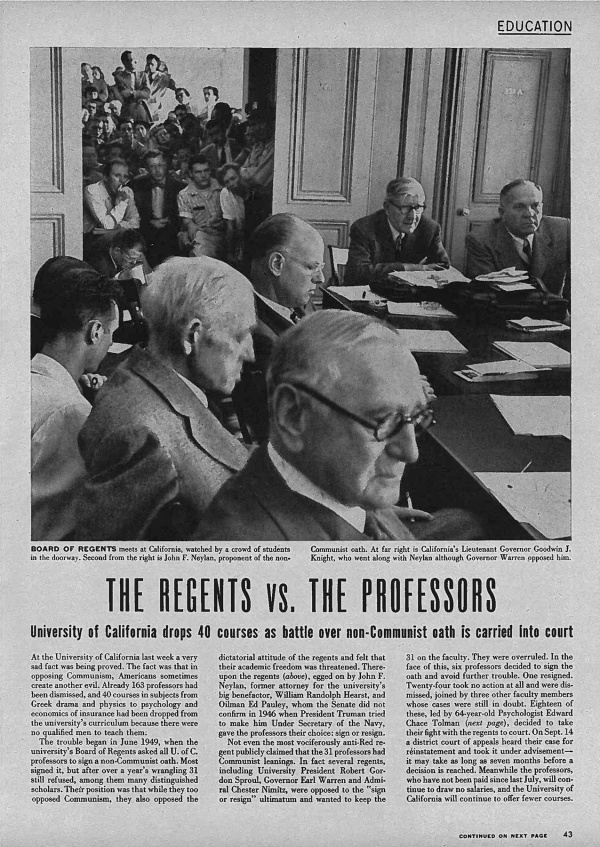

After various failed attempts to mediate, compromise or walk-back the oath in the face of widespread opposition from the UC faculty, the next major turning-point occurred at the February 24, 1950 Regents’ meeting. By a vote of 12 to 6, led by Regent Neylan, who was angry at Sproul for having subjected the Regents to the blowback against the oath and ready to embark on a power struggle with the faculty over governing authority in the university, the Regents passed the so-called “Sign or Get Out Ultimatum,” the name of which is fairly self-explanatory: any faculty member’s failure to sign the oath would be interpreted as severance of employment with the university. Not only did this rouse the faculty to new heights of indignation, but it also led to increased activism among students and non-Senate employees. In a spectacular show of concern for the events transpiring at the university, between eight and ten thousand students, or nearly half the Berkeley student body, gathered at the Greek Theater on March 6, 1950 for discussion and protest of the loyalty oath.

The final decisive turning point came shortly after, when Governor Earl Warren, who was by office the head of the Regents and who personally opposed the loyalty oath, was able to appoint two new Regents and reappoint another (though this reappointment was of the Bank of America scion L. Mario Giannini, who politically was even more reactionary than John Francis Neylan). The appointment of two, more liberal Regents raised hopes that a compromise might still be reached to resolve the crisis. Yet at the March 31, 1950 meeting, Regent Neylan insisted on pressing ahead with an April 30 dismissal deadline and managed to wrangle a deadlocked 10-10 vote, meaning the deadline still stood. Even Berkeley’s Dean of the College of Chemistry Joel Hilderbrand, who up to that point had played a conciliatory or even conservative role during the crisis, reached his wit’s end with the Regents. As Blauner reports, at a mass meeting at the Greek Theater on April 10, 1950, Hilderbrand expressed his exasperation in a speech: “He… pointed out originally a UC professor had only one offense to be concerned about, that of being a communist. Then came a second offense: failure to sign the oath. And now a third had been added, opposing the regents. ‘Is docility necessary for a professor?’ he asked in conclusion.” At this point, a group of concerned and influential alumni attempted a last-ditch effort to save the day, which came to be known as the “Alumni Compromise.” This compromise was adopted by the Regents 21-1 at their April 21, 1950 meeting (the one opposing vote was Regent Giannini, who predicted celebrations in the Kremlin if the measure passed; Stalin’s reaction, however, was unremarked in the official minutes.).

The compromise was to include three measures: the loyalty oath requirement would be rescinded; it would, however, appear in identical wording on the contract that had to be signed, which hardly satisfied those who objected to the oath as such. Lastly, and importantly, refusal to sign would not entail automatic dismissal, but the Academic Senate’s Committees on Privilege and Tenure would hold hearings for non-signers, giving them the opportunity of alternative means of attesting their loyalty (for example, presenting previous U.S. government security clearance) and the chance to explain their reasons for refusal of the oath. Still, in a final step that would prove fatal for the compromise, the Regents would retain ultimate authority over the non-signers’ reappointment or dismissal.

In the months following the April acceptance of the Alumni Compromise, the Committees on Privilege and Tenure conducted hearings, recommending for reappointment sixty-one Senate faculty who had not signed (six were not recommended). By the July Regents meeting, the number of non-signers had further dwindled as additional faculty members, who had until then held out, finally signed. In a cliff-hanging vote, the recommendation by President Sproul to accept P&T’s recommendation of reappointment for the remaining non-signers was passed 10 to 9. However, in a questionable parliamentary maneuver, Regent Neylan changed his no vote to yes, which allowed him to request that the whole matter be revisited at the next Regents meeting in July. The Regents’ majority vote was left in suspension and the deadline to dismiss remained in place. The Neylan faction by this point wanted heads on pikes, and objected to the high number of non-signers that the Committees on Privilege and Tenure, through its hearings, had cleared. At the August 25, 1950 meeting, by a 12-10 vote, the Regents overturned the July vote to reappoint the recommended non-signers, and non-signers were now given ten days to complete the oath or be dismissed. Thirty-one were fired in the coming weeks.

In the aftermath of the firings, the University of California was subject to widespread boycott, censure, and other reputational harm. Within the university and across the country, professors donated money to support the faculty who had been fired and help them in their searches for new positions elsewhere. At the same time, a suit was launched by Edward Tolman and nineteen other fired faculty against the Regents, Tolman vs. Underhill, which was ultimately decided in favor of the dismissed professors on April 6, 1951. Although the decision made passing reference to the issues of academic freedom the case raised, it mostly sidestepped these in favor of a narrower ground for its ruling: that the University of California’s oath had exceeded the constitutional oath stipulated by the California Constitution and illegitimately supplanted it. The plaintiffs had, in any case, won the right to be reinstated in their positions. The Regents, for their part, were indecisive as to whether to appeal the decision, but as the rules allowed, one Regent could file the appeal individually and Regent Sidney Ehrman did so. It was thus not until October 17, 1952 that the lower court’s decision was definitively upheld in the state’s Supreme Court and non-signers received the backpay owed them and could be reinstated, if they wished, to their positions. The higher court’s decision was based on grounds as narrow as those of the preceding decision, leaving the academic freedom issues undiscussed. By the time the Supreme Court was hearing the case, the Levering Act, which instituted an even more onerous anti-communist oath for all California public employees, had been passed by the legislature and thus superseded the Regent’s oath.

IV. Lessons from the History of Academic Freedom

Why should we occupy ourselves with this episode from the by-gone history of the University of California? The events, to be sure, have intrinsic interest for some, for California history buffs, for education wonks, or perhaps for those who discern dramatic lineaments among its cast of Machiavellian Regents, vacillating administrators, heroically perorating faculty, and acerbically irreverent students. But it may also prove instructive in other ways in what looks to be a coming time of trouble ahead for the university. I will mention in brief three such lessons, with more detailed explanation to be deferred, necessarily, for another occasion.

The first is the sheer fact that the University of California has been around this perilous block before. One of the most prominent clichés today, to be found everywhere in our journalism and public commentary, is that the distressing phenomena of our time are “unprecedented.” They are not. Looking back on the California loyalty oath crisis, we learn the hard lesson that the politics of fear, worked by ambitious powerbrokers and ineffectually parried by university leaders, could in fact wreak enormous damage on our university, on individual lives and careers, and on the integrity and reputation of the institution. Some losses, such as the potential contributions of those faculty and students who left or never came in the first place, remain incalculable. The means and will of the university to defend academic freedom against political interference proved weaker than expected, and such victories that were won were only partial and often Pyrrhic. In the long run, however, we also see that within the framework of a stressed but not broken American democracy, the political fortunes of the university’s most dangerous opponents declined with time and growing resistance, while the University of California’s community of researchers, instructors, and learners endured. There are plenty of conjunctural social and political reasons for this outcome, but there are also consistent ethical reasons, and it is these latter I want to underscore. The university community’s commitment to the mission of public education, to the value of excellence in research and instruction, and to the free pursuit of truth and knowledge among peers and students may have been weak as short-term instruments against political or legal attack, but they remain strong long-term pillars of an enduring, resilient university. There is still strength today to be gained from knowing that these pillars have withstood past trials, and they may do so in the future as well.

The second, and more controversial, lesson is that already in 1950 the conception of academic freedom expressed in declarations such as the American Association of University Professors’ 1915 “Declaration of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure” and the 1940 “Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure” had begun to show its limitations. I can only briefly say why I think this is so. As the historian Walter Metzger has suggested, the framers of the AAUP principles saw the primary danger to academic freedom to be the representatives of values “external” to academic ones who are nevertheless “inside” the university and capable of exercising their influence there. Above all, this meant trustee boards and those administrators that they directly selected, along with overreaching donors, against whose direct and excessive influence in university affairs the faculty of the university sought to protect themselves. (This view was clearly reflected in the subtitle of Thorstein Veblen’s spirited polemic of 1918, The Higher Learning in America—A Memorandum on the Conduct of Universities by Business Men.) While this was by no means an unfounded concern, as the role of certain Regents in the loyalty oath crisis indeed suggests, overall it led the framers of the AAUP principles to a very partial and parochial view of academic freedom.

“In their preoccupation with this problem,” Metzger suggests, “American academics came firmly to believe that the primary concern of academic freedom was with what happened in a university, not with what happened to a university—that an offense against academic freedom was essentially an inside job.” In other words, there was far less attention paid to the definition of academic freedom derived from and protected by the social, political, and legal status of the university and college institution. To be sure, the rights of individual faculty to freedom in their research and teaching are essential, but it is also useful to highlight what is downplayed or even excluded in this conception of academic freedom essentially centered on individual faculty rights and interests.

One thing downplayed in the AAUP principles, for instance, was academic freedom as it pertains to students, other than as benefits they derive from being taught by professors free to pursue research and instruction as they see fit. This limited sense of student academic freedom—in stark contrast to the near-anarchic “Lernfreiheit” (freedom in learning) of students in the 19th-century German universities—was also consistent with the peculiarly strong focus on undergraduate education in American colleges and universities and the overarching in loco parentis guidance that undergraduates continue even today to receive from professors, curricular programs, advisors, tutors, and student affairs professionals.

In fact, academic freedom as applicable to learners has typically been given more serious attention by conservatives wary of the climate of ideas and instruction in the post-war university than by its liberal defenders. William F. Buckley’s famous conservative manifesto God and Man at Yale, subtitled The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom,” was published in 1951 and thus appeared just in the aftermath of the California loyalty oath crisis. In it, the recently graduated Buckley accused Yale’s liberal professoriate of forcing collectivist social and economic ideas and secularism on its impressionable young undergraduate men (they were all men until 1969), at the expense of the intellectual foundations of individualism and Christianity that Yale’s supporting patrons—its trustees, donors, parents, and alumni—expected students to learn in “their” university. Buckley argued that given the failure to attend to the freedom of learning of Yale undergraduates against liberal indoctrination, these patrons should rise up and intervene to realign the institution’s teaching with their values, even if this might mean purging the ranks of offending professors and hiring new, more appropriately oriented ones. Buckley’s argument has become a staple for subsequent conservative critics of the university—essentially the same argument, warmed over without its originator’s rhetorical vim, is still being made three-quarters of a century later. But however one might consider the substance of Buckley’s view (which, it should be clear, I am far from endorsing), it is hard to deny that he identified a very wide strategic gap in the AAUP position that at least partially justifies the ironic scare quotes he puts around “academic freedom” in his title. How real is “academic freedom,” Buckley was in essence asking, if students can only be the accidental and occasional beneficiaries of their professors’ individual freedoms? Buckley’s challenge was to expand the question of academic freedom to full institutional scale, where students also have distinct stakes and interests in academic freedom that should not be reduced to just an afterthought or an epiphenomenon of a free faculty. We need not accept Buckley’s particular answers to acknowledge that he posed a legitimate, sharply aimed question to which the reigning doctrine of academic freedom was ill-prepared to respond.

Also largely excluded from the AAUP principles were bolder social and political means for securing academic freedom at collective and institutional levels, for instance, “syndicalist” attempts to unionize faculty to enforce their collective will; direct legislative regulatory protections of collective academic freedom; or other political means to limit extra-academic influences on universities, such as legal checks on the practice of governors’ appointing political allies to trustee roles. Ironically, it was the old conservative Kantorowicz, in arguing for a strongly self-governing faculty akin to that of late-19th-century German universities, who bluntly spelled out the alternatives that the loyalty oath affair had set into relief. Not without an element of implicit threat, Kantorowicz wrote:

Only as long as certain vested and autonomous rights of the body of teachers and

students are respected can the professors refrain from forming a “union”…. If really

they are hired on a business basis, then they will have to organize in a business

fashion and establish their union. Actually, the present intransigent and shortsighted

policy of the anything but conservative radicals among the Regents of the

University of California might very easily touch off a general movement aiming

at unionizing the American university professors.

It is all the more striking that Kantorowicz brings up faculty unionization so forthrightly, given his evident indignation at being lumped in by the Regents with the university’s janitors and gardeners as an “employee” and the anger with which he greeted the Regents’ “inconsiderate experiment,” to “uproot one of the few relatively conservative sectors of modern society, that of university professors.”

The last point follows closely from the previous. There has been a great deal of attention recently paid to the so-called “politicization of the university,” both from those who would seek to conduct partisan politics within the university and from those who hope that such inner-institutional politicization might be “neutralized” (or, as is perhaps often the case, those who would prefer that their own partisan politics commanded more university real estate). Paradoxically, such “hyper-politicization” within the institution may have left the university increasingly disarmed against a hostile politics writ broadly, a politics of the university that is being fought out, with dangerous implications, outside its gates.

It has become a commonplace of current writing on academic freedom that hyper-politicization within the university, the emergence of what political scientist Gregory Conti calls “the rise of the sectarian university,” is threatening academic freedom by undermining its principles from within. Such internal threats to academic freedom, it is furthermore claimed, invite external interventions that are becoming more common as university politicization intensifies, such as legislative programs to curb supposedly compromised instruction and to impose, under threat of sanctions, “viewpoint diversity” among the faculty and in the classroom. I would suggest that such analyses get things wrong, above all by suggesting that inner-institutional politicization is the cause of the external attacks. We should be abundantly clear that such attacks on universities do and will continue to exist independently of the specifics of what goes on in university lecture halls and seminar rooms, for they have become a strategic mainstay in the general political environment of our day. These attacks are motivated not out of well-meaning desire for the reform of universities, but rather with the avowed aim of subjugating an important institution that remains, in the eyes of some political actors, too independent from their own political ideology. There are, to be sure, plenty of things deserving of criticism and change in today’s universities, but this is no reason for universities to accept the blame for political attacks that have very little to do, in the end, with what actually goes on within our walls. Today’s university suffers less from a direct weakening of academic freedom through internal politicization, as from the debilitating persistence, even under the contemporary alibi of hyper-politicization, of what Metzger called academia’s “inward-turning moral sociology”: its myopic focus on moralized, inner-institutional “goods” and “bads,” which renders its defense of academic freedom feeble in moments of genuine political challenge like during California’s loyalty oath crisis or, I would dare say, in the situation in which we find ourselves today.

In my view, we should think of academic freedom not, as we are often invited, as a matter of finding our way back to some neutral and depoliticized place, but on the contrary as a profoundly political issue—an issue that calls for engaged advocacy in the public and legislative domain in which its fate is actually being decided, not the inner-institutional space where so much passion and energy have been expended over so many decades. What might constitute the basis of a more adequate politics of the university to protect the public good that they may continue to do in the 21st century? The question goes beyond the span of this essay and, as well, to some extent beyond my ken as a non-expert in relevant areas of politics, law, and educational policy. What can be said is that our current political horizon is posing acute existential questions to universities. In response, we need to start devising new, better answers than in the past about the university’s essential bases and purposes, and our responsibilities and rights in executing them. For those of us who work in universities, these have become questions of pressing urgency, questions that are anything but “just academic” and towards which the stance of so-called “neutrality” might prove fatal.

Selected Reading

Giorgio Agamben, The Sacrament of Language: An Archaeology of the Oath (Stanford University Press, 2011).

AAUP, “General Report on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure,” December 15, 1915.

AAUP, “Statement on Academic Freedom and Tenure,” 1940.

Bob Blauner, Resisting McCarthyism: To Sign or Not to Sign California’s Loyalty Oath (Stanford University Press, 2009).

William F. Buckley, Jr., God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom” (Henry Regnery, 1951).

Erwin Chemerinsky and Howard Gillman, Free Speech on Campus (Yale University Press, 2017).

Gregory Conti, “The Rise of the Sectarian University,” Compact, December 28, 2023.

Simon During, “The Right-Wing Medievalist Who Refused the Loyalty Oath: Ernst Kantorowicz, Academic Freedom, and the “Secret University,” Chronicle of Higher Education, November 20, 2020.

Erik Erikson and editors, “Editorial Notes: The California Loyalty Oath,” Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes 14/2 (1951).

Stanley Fish, Versions of Academic Freedom: From Professionalism to Revolution (University of Chicago Press, 2014).

David P. Gardner, The California Oath Controversy (University of California Press, 1967).

Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States (Harvard University Press, 1970).

Richard Hofstadter and Walter P. Metzger, The Development of Academic Freedom in the United States (Columbia University Press, 1955).

J. Edgar Hoover, Letter from the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation to the President’s Special Consultant, July 7, 1950. National Archives, RG 273, Files of the National Security Council Representative for Internal Security 1947–69, Box 36, Problem 11.

Harold M. Hyman, To Try Men’s Souls: Loyalty Tests in American History (University of California Press, 1960).

Ernst Kantorowicz, “Inalienability: A Note on Canonical Practice and the English Coronation Oath in the Thirteenth Century,” in Selected Studies (J.J. Augustin, 1965).

Ernst Kantorowicz, The Fundamental Issue: Documents and Marginal Notes on the University of California Loyalty Oath (Parker Printing, 1950).

Clark Kerr, The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949-1967, volume 1: Academic Triumphs (University of California Press, 2001).

Robert Lerner, Ernst Kantorowicz: A Life (Princeton University Press, 2017).

Robert P. Ludlum, “Academic Freedom and Tenure: A History,” The Antioch Review 10/1 (1950).

Carey McWilliams, Witch Hunt: The Revival of Heresy (Little, Brown & Co., 1950).

Walter P. Metzger, “Academic Freedom and Scientific Freedom,” Daedalus 107/2 (1978).

Franz L. Neumann and Otto Kirchheimer, The Rule of Law Under Siege, ed. William E. Scheuerman (University of California Press, 1996).

Jacob Hale Russell and Dennis Patterson, “How to Save the American University,” The Guardian, August 24, 2025.

Ellen W. Schrecker, “McCarthyism: Political Repression and the Fear of Communism,“ Social Research 71/4 (2004).

Ellen W. Schrecker, No Ivory Tower: McCarthyism and the Universities (Oxford University Press, 1986).

Adam Sitze, “We Need a New Theory of Academic Freedom,” Inside Higher Education, July 22, 2025.

George R. Stewart, The Year of the Oath: The Fight for Academic Freedom at the University of California (Doubleday, 1950).

Thorstein Veblen, The Higher Learning in America: A Memorandum on the Conduct of Universities by Business Men (B.W. Huebsch, 1918).

Max Weber, “Science as Vocation.” In Max Weber’s Complete Writings on Academic and Political Vocations, ed. John Dreijmanis (Algora Press, 2008).

Keith E. Whittington, You Can’t Teach That! The Battle Over University Classrooms (Polity, 2024).

Mark G. Yudof, “Intramural Musings on Academic Freedom,” Texas Law Review 66/7 (1988).

Mark G. Yudof, “Three Faces of Academic Freedom,” Loyola Law Review 32/4 (1987).