By Megan Cole

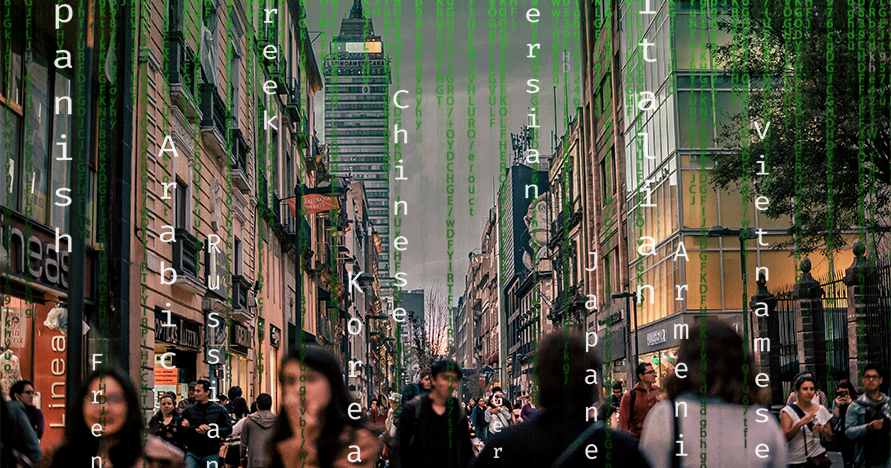

Starting this spring, UCI language students will be able to wander through the streets of Vietnam, practice Tagalog in the Philippines, explore the Arabic-speaking world and more — all from the comfort of a small, unassuming classroom in the Humanities Instructional Building.

UCI’s Program in Global Languages & Communication (GLC) will soon launch the Intercultural Communications Lab, a virtual-reality-enabled classroom wherein students can don headsets to “travel” anywhere in the world. The lab’s cutting-edge software will enable users to virtually navigate foreign cities, converse with native speakers and experience total linguistic and cultural immersion without the costs of studying abroad.

Initially, the lab was conceptualized as a response to the “uncertainty” of COVID-19, according to English Professor and GLC Director Jerry Won Lee. When the pandemic broke out, Lee was working on a book about Korean language and culture in global contexts. He soon realized how difficult it was to conduct internationally focused research without the ability to travel.

“The pandemic disrupted traditional scholarship and learning on every level, and made everyone think more creatively and intentionally about technology,” says Lee. “As academics and as language instructors, my colleagues and I began to wonder: If we can’t travel and convene in person, how do we get students interested in language-learning? If we can’t take our classes on actual field trips to practice reading and interacting in different languages, can we construct a more feasible version of that? We realized that virtual reality is the next best thing.”

Building a lab for language learning, and more

Global Languages & Communication faced some challenges getting the lab off the ground, including the ongoing pandemic and the cost of equipment — the lab comprises two 75-inch monitors connected to Oculus virtual reality (VR) headsets, as well as two interactive, floor-to-ceiling glass whiteboards for collaborative work. However, after its soft launch later this spring quarter, the lab will be available to students in various courses. By fall 2023, GLC expects to open its doors to an even wider array of students.

Though certainly not the first VR lab in the University of California system, UCI’s School of Humanities VR lab is the first in the UC to focus on language instruction, specifically for undergraduate students. On a campus where students can study 14 languages other than English and major or minor in several of these, innovative language instruction is essential. “Fluency in languages other than English has enabled our students and alumni to study and travel abroad, to launch careers overseas and to deepen their connection to their own cultures and to that of others,” explains Dean of Humanities Tyrus Miller.

Though built for language instruction, the lab presents other opportunities for instructors looking to connect students with worldly environments. “While the lab was originally intended solely for students taking language courses offered by the GLC — for instance, Vietnamese, Arabic and Persian — we hope eventually to welcome students in other language courses and perhaps in other disciplines altogether,” says Lee. Beyond language study, he notes, humanistic applications for VR technologies are practically endless. History students might virtually explore ancient ruins; art historians might “visit” museums across the world; and literature students might walk through the real and fictional cities featured in the novels they read.

Due to the myriad possibilities enabled by VR technology, it has recently become “one of the most prominent trends and points of interest in humanities research broadly,” says Lee. Indeed, across UCI Humanities, scholars are currently leveraging the power of VR in their research and pedagogy. Among others, English Ph.D. candidate Dalton Salvo is using virtual reality to revolutionize remote teaching, and Italian Studies Professor Deanna Shemek is using similar technologies to bring a sixteenth-century female ruler’s studio back to life.

"The value of VR for educational purposes extends beyond the Humanities to most if not all fields of study,” Salvo notes. “As it is a virtual world, we are not limited by physical classrooms and traditional linear learning; but rather can build entire environments designed to teach a concept, practical skills or body of knowledge. VR technology allows students to experience the virtual environment through a first-person perspective. Along with interactive elements such as navigating a foreign city to help promote language learning through immersive activities, it provides students with a novel, intimate and more participatory learning experience than a simple lecture.”

For Lee and his colleagues, VR represents much more than a passing fad. It enables the breakdown of material barriers, promotes equity and amplifies student success. “With the Intercultural Communications Lab, our ultimate goal is to bring as many opportunities as we can to humanities students who — for whatever reason — can’t conduct international research or pursue travel opportunities outside of the classroom,” says Lee. “We are invested in digitization because we believe it increases the accessibility of research and learning methods and, most importantly, helps to level the playing field.”