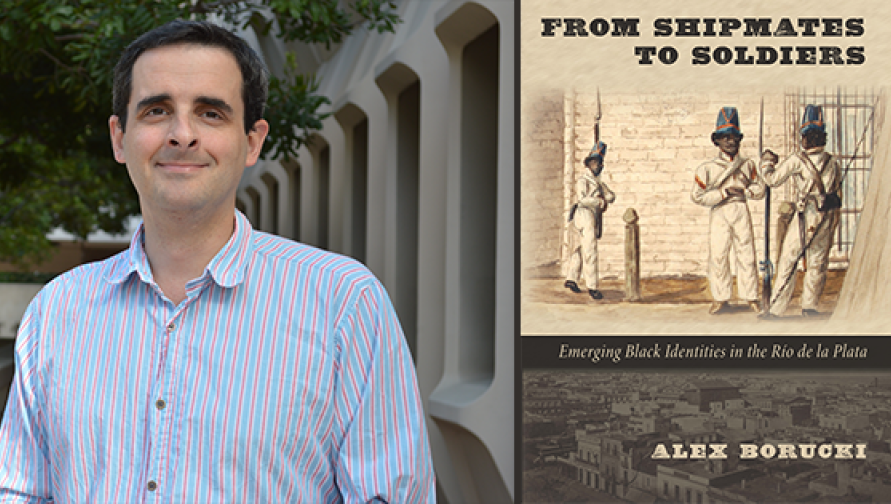

From Shipmates to Soldiers, Emerging Black Identities in the Rio De La Plata (University of New Mexico Press, 2015) by Alex Borucki, assistant professor of history, published this fall. The book analyzes the lives of Africans and their descendants in Montevideo and Buenos Aires from the late colonial era to the first decades of independence. In the Q&A below, we discuss the writing process, the book itself and what’s next for Borucki.

1. You have written four books before this one. How was researching and writing this book different from your other book projects?

My first two books in Spanish were socio-economic studies of slavery and abolition in Uruguay. From Shipmates to Soldiers is much more expansive as it focuses on black populations in Montevideo and Buenos Aires, and their connections with both Brazil and Africa. For this project, I had to conduct archival research in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Spain, and England. I lived with two pieces of luggage for eighteen months while I was in these sites. Writing also began at this stage, as I first tried to systematize information, for instance, by entering data on slave voyages into databases. But the most demanding part of writing was going through the several rounds of revisions with the team of editors at University of New Mexico Press, a great group of professionals.

2. What led you to this area research?

As was the case for other Latin American countries, with the exception of Cuba and Brazil, scant recent research existed on the local history of slavery when I began to conduct historical research in the early 2000s. While black populations were very large in the colonial era in countries such as Colombia, Peru, and Uruguay, they now constitute much smaller minorities, which contributed to making slavery “tangential” for national histories. This systematic lack of knowledge and interest has sparked my curiosity. In addition, Argentina and Uruguay are nations long constructed as ‘white’ in the context of Latin America, because the majority of the populations are descendants of Europeans who migrated from the late 19th century to the mid 20th century. Writing about the people of African ancestry in these countries is not only innovative but also necessary in order to conceive more inclusive national narratives.

3. How does your book complicate—or add depth to—our understanding of the histories of the African Diaspora?

For Latin America, I argue that black social identities emerged from shared slave routes, the reshaping of ethnic boundaries, and black participation in social organizations including black Catholic confraternities, free black colonial militias, African-based associations (such as the group of the “Congo”), and later, black participation in the national armies in the nineteenth century. Moving beyond the existing historiography that has focused only on particular aspects of this story, I show the interconnectedness of these arenas and how individuals operated across these contexts. For instance, black confraternity leaders influenced the command structure and style of free black colonial militias in late eighteenth-century Montevideo and Buenos Aires. Also, continuous recruitment of slaves into the independence-era armies shaped aspects of mid-nineteenth century African-based celebrations. These types of organizations are central to our understanding of slave and free black life as they were the carriers of black cultures in Latin America, and also the organizational defense of people subjugated by slavery, or in the case of the free black population, by its proximity.

4. Your book spotlights Jacinto Ventura de Molina. What should we know about him?

Molina was a black writer who lived between 1766 and 1841, first in the borderlands of the Spanish and Portuguese empires in South America, then in Buenos Aires, and, much of his life, in Montevideo. His case is exceptional as very, very, few writings produced by authors of African ancestry survived for nineteenth-century Latin America (you can count them with your hands). While his parents were Africans, he lived very close to Spanish military officers, who taught him literacy. He wrote profusely about the Spanish monarchy, Catholicism, the African-based organizations, and his desire to be able to litigate in court. He was an urban legend in 1830s Montevideo, but after his death he fell into oblivion. Few local intellectuals were likely to have had much sympathy for Molina in most of the twentieth century. While the Uruguayan literary canon depicted the country as a white nation against the backdrop of mixed-raced Latin America, Afro-Uruguayan writers portrayed the contributions of slaves and freedmen as essential to the emergence of the nation. According to nationalists, Molina supported the wrong side when Uruguay became independent, as he remained loyal first to Spain and then to Brazil. In sum, Molina defies easy explanations.

5. What’s next for your research?

In my current book project, entitled Slaves, Silver, and Atlantic Empires: The Slave Trade to Spanish South America, 1660-1810, I plan to study the connections between slave arrivals in Colombia, Venezuela, Argentina and Uruguay in the eighteenth century and the remittances from these colonies of the silver that came to link trading circuits in the larger Atlantic world, as Spanish American silver was the bloodline of the Atlantic economy. I will analyze how Spanish colonial expansion, as well as Portuguese and English imperial and trading designs on Spanish South America, were entangled with the slave trade. I will look at how Spanish imperial policies had different effects in each of these colonies depending on the tactics of the local elites, their connections with non-Spanish traders, and the patterns of Atlantic trade. In sum, I will examine the European empires in the era of Atlantic slaving and the people caught up in the slave trade by focusing on the colonial politics, the interconnected economies of slave trading and silver circulation, and the stories of Africans arriving in Spanish colonies.