By Lilibeth Garcia

As fascism and antisemitism violently transformed the early and mid-20th century, two key figures sought to understand the divided world they lived in. In doing so, they developed novel concepts not just to criticize – but also to help resist – the authoritarian regimes of modern Europe. Almost 100 years later, their work continues to resonate with activists and scholars worldwide.

The insights of George Lukács and Theodor W. Adorno set the foundations for the philosophical approach and school of thought known as “critical theory,” sometimes also referred to as Frankfurt School theory because of its association with the German city’s radical intellectual traditions.

Critical theory has since been immensely influential in the study of history, literature, culture, law and the social sciences. In fact, at UCI, critical theory has for decades been one of the most distinctive and recognized features of humanities scholarship.

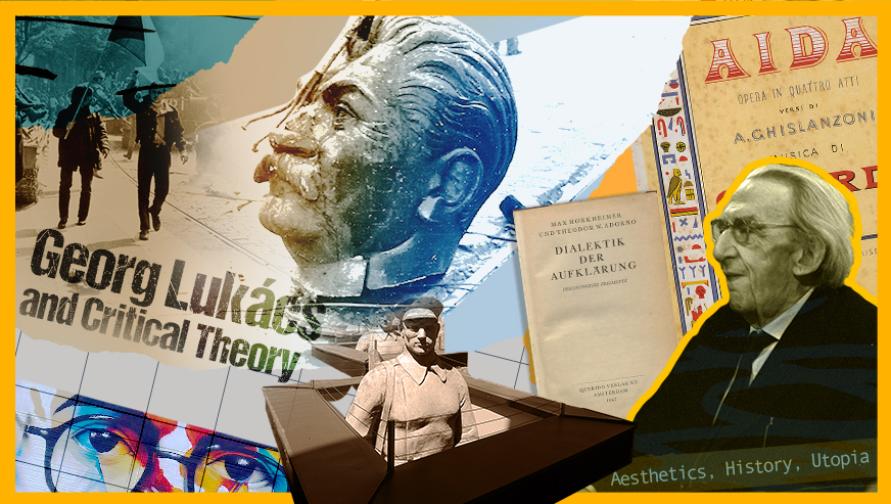

Although Lukács and Adorno came from privileged backgrounds that in certain respects mirrored one another, these two philosophers approached their increasingly polarized societies with diverging approaches and perspectives. Their stories and theoretical outlooks are documented in the new book by School of Humanities Dean and Professor of Art History and English Tyrus Miller, Georg Lukács and Critical Theory: Aesthetics, History, Utopia (Edinburgh University Press, 2022), which is being published in both a print and a free open access e-book edition.

“We can think about these two Central European Jewish thinkers and their response to modern culture as very sensitive antennae picking up on the various forces of the modern world and formulating them into a criticism of contemporary culture, a critical theory of society and a set of radical political views,” Miller says.

The culmination of two decades of research and previous translation of Lukács’s work, Georg Lukács and Critical Theory examines the theories of Lukács and Adorno as windows into understanding the 20th century and, by extension, the world we live in now. Through discussions of utopian thought, drama, visual arts, music, film and media, avant-garde, kitsch, post-socialist museums, show trials and more, the book focuses in on a broad range of interdisciplinary subjects studied by Lukács and the Frankfurt School.

Parallel lives for a polarized world

Despite being born two decades apart, Lukács and Adorno had analogous upbringings. Lukács came from a wealthy Hungarian-Jewish, aristocratic background, but amid the political uprisings in Hungary in 1918-1919, he suddenly became a committed communist revolutionary and activist thinker. Adorno similarly came from a privileged, deeply cultured German-Jewish background, and like Lukács, came under the influence of Marxism and developed into a critic of capitalist society and its culture – though one far more pessimistic than Lukács about the possibilities for active political change.

Lukács was especially immersed in European literature as a literary critic. As a teenager, he even convinced his banker father to pay for him travel to Norway to meet his early literary hero, the playwright Henrik Ibsen. Adorno was, in contrast, a trained composer, who studied in Vienna with the modernist composer Alban Berg.

Throughout his life, Adorno wrote penetratingly about music alongside philosophy and social theory, whereas Lukács admitted he had no understanding of music at all (even though his sister’s piano teacher was the composer Béla Bartók). Lukács’ artistic tastes were conservative, favoring the writings of classic European writers such as Dante, Cervantes, Balzac, Goethe, Tolstoy and Thomas Mann. Adorno, for his part, was a militant artistic modernist, celebrating the writings of Kafka and Beckett and the dissonant music of Schoenberg, Webern and Berg.

When the Nazis came to power, Lukács fled East into exile in Moscow, while Adorno emigrated West, going to London, New York and eventually Los Angeles. After World War II ended, Lukács returned to Hungary and stayed until his death, despite living for decades in personal danger from the communist authorities there, while Adorno came back to Frankfurt, in what had recently become “West” Germany. They spent the rest of their lives, thus, on opposite sides of the Iron Curtain. Their parallel lives and the impact of their antithetical choices on their thought offer a template for understanding the deeply politically polarized early 20th century, claims Miller.

“Lukács and Adorno are very sensitive and deep diagnosticians of the modern condition. They are among the most profound, and yet they ended up with very different views, and, in fact, clashed with one another very sharply in a few cases,” says Miller. “In certain respects, their intellectual relationship embodied a metaphor that Adorno once used in another context: ‘Torn halves that do not add up into a whole.’ They took up strong – and notably ungenerous, even willfully blinded – positions against one another, whereas neither really managed to get to the true root of their controversy, which was the devastation of the ideal of socialism at the hands of Joseph Stalin.”

Miller started reading Lukács, Adorno and the Frankfurt School as an undergraduate student – an interest that led him to study not only German but also, later, Hungarian. His long-lasting interest in the 20th century was born out of his own experience of growing up in what turned out to be the late phases of the Cold War, when it nevertheless seemed like the world would always be divided between the communist countries and the capitalist countries – the East and the West.

“The 20th century – for me – was those two worlds and the complex metabolism between them,” Miller says. “Thinking about Lukács in Hungary and Adorno in West Germany allows me to focus on that kind of ideologically shaped world, on how the ‘divided’ mindset of that time was a powerful fact of life affecting millions of people in its social, physical, cultural and existential dimensions.”

Predicting 21st century social trends

Some of Lukács theories were ahead of their time. He developed the concept of reification, the “turning of processes and activities into a thing,” as he observed how social relations under capitalism were transformed into quantifiable and exchangeable commodities.

In the early 20th century, Lukács suggested, social relations were increasingly losing their connection to values such as community, love, empathy and respect, and instead were being translated into economic terms of profit and loss.

A striking example of how reification has manifested in current society, for example, is how social media interactions – say, a Facebook exchange of messages and photos between family and friends – are converted into data that are sold to companies who then use those exchanges to market products to users. Though, of course, they could not have anticipated this precise form of reification, Lukács and the Frankfurt School theoreticians foresaw the general trend in which social interactions may be manipulated by an algorithm designed to maximize consumer spending.

Likewise, the very existence of now-commonplace concepts like “human capital” and “human relations” (typically abbreviated to “HR”) suggest how individuals’ lived experiences are regularly abstracted into calculable economic values. Already in the 1920s and 30s, Lukács and the Frankfurt School were identifying the early form of tendencies that almost a century later would come to define the world of work as millions of people now know it.

“Lukács was looking at how a whole range of social relations and activities are seen in terms of objects that we can calculate, buy and sell,” Miller explains. “Social relations that we may experience as warm and intimate are actually being made into a ‘thing’ that circulates on the market with a monetary value attached.”

The future of critical theory

Critical theory has continued to expand and diversify since the days of Lukács and the early Frankfurt School. At the UCI School of Humanities, for example, the Culture and Theory Ph.D. Program is home to leading scholars of Africana thought, postcolonial theories from all geopolitical regions, Marxist and psychoanalytic criticism, and continental philosophy – all newer branches of the critical tradition.

Many other departments and programs in the humanities have a similar breadth and depth of engagement with critical theory for research in gender and sexuality, literature, visual culture, media, race and ethnicity, history, and philosophy.

Yet despite many innovations in critical theory since Lukács and the Frankfurt School, their writings remain relevant to read today in new contexts.

“In recent years, sadly, we have seen a reemergence of the authoritarianism that shaped Lukács’s and Adorno’s world in such violent and terrible ways,” Miller says. “Both were thinkers who were highly motivated by fear of and resistance to fascism. Both wrote under the shadow of exile and repression by fascist and Stalinist political regimes. Along with new applications of critical concepts, such as reification by contemporary critics, their work has again become topical precisely because the dangers of fascism, antisemitism and other forms of race-hatred, and authoritarian politics are still highly relevant.”