In Summer 2023, School of Humanities first-generation students interviewed first-generation humanities faculty to learn about their experiences and the different professional and personal paths they traveled on their way to UCI.

Pasadena > Palo Alto > Massachusetts > Palo Alto > Los Angeles > Michigan > Arizona > Irvine

In this interview, Chloe Vo (B.A. Asian American studies ‘26) speaks with Professor Bambi Haggins (Film and Media Studies) about her time as an undergraduate and M.A. student at Stanford University, her commitment to public education, having a “ride or die” family and her willingness to see the advantages in the disadvantages. What follows is an edited version of the transcript from their in-person conversation.

Chloe: When did you first recognize that you were a first-gen student? And how did that change your perspective?

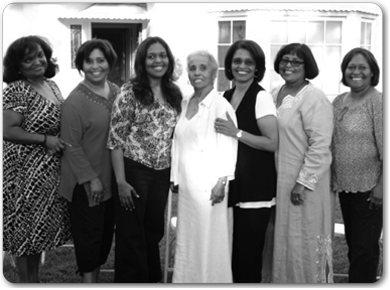

Bambi: I had no doubt that I was a first-gen student. I was fortunate enough to go to Stanford for undergrad. And at the time – well, they still do have this policy of blind admissions – so they let you in and then help you figure out how to pay. Of course I had some loans. I am from a working class family. Five sisters. My pop was a construction foreman, and my mom did some work out of the house but mostly she was trying to take care of six kids. And she was also absolutely brilliant. Because she managed to give us all the extra things, like the lessons and all of that, but on a construction foreman’s salary. Because of the way she did it we didn’t necessarily feel like they were sacrificing. We were raised pretty much like middle class kids, but not on a middle class income.

But at orientation at Stanford I learned about generational wealth, and about legacy admissions and all of that. Because there were people who were just rich. They were stupid rich. And I equate that with first-generation because I mean, honestly, a lot of us are first-gen, have parents who were more than capable of being able to go onto higher education. But that just wasn't possible – fiscally, socially, culturally – at the time. And that went along with the adage that you can't be as good, you got to be twice as good to get half as far. And that was rooted not only in class, but in race. And in gender. You know, I'm old. I was in college in the 1980s. And that was the “greed is good” era. And so I'm glad that at least the way the university was built was very much trying to be of aid to the students who were there. But you know the difference. You didn't summer on the Cape. You didn't go to Cozumel for spring break. And you weren't already world traveled before you got to school. And rather than having that make me feel less than, I think it put more fight in me. That I can do this.

The Power of a “Ride or Die” Family

C: In terms of that feeling of determination that you had, was any of that from your parents (within your family)?

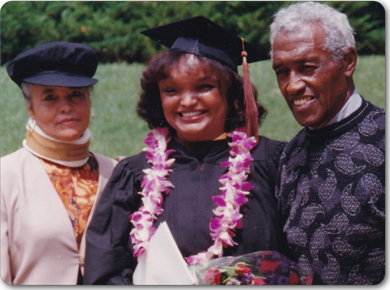

B: Absolutely. School was our job. They truly bought into the idea that education is the only way to have actual mobility. And that's the case. There's six of us, and neither mom nor dad had a college degree. And all six of us went to college. I have a Ph.D. and my youngest sister has an M.A. We are professionals, teachers, working for Jet Propulsion Laboratory, etc. There was an expectation that because you got to do school and get the extracurricular activities that enabled you to get into a good school, that all that effort wasn't going to be wasted. And yeah, there was pressure, but there was always also presence, being there to be supportive. And I was kind of an extra challenge, because I was the sick kid, basically from four to 17. Strangely enough, again, from 58 to the present. And so there were a lot of other challenges. But personal responsibility was also good. Having a family that understands what you're trying to do and encourages it is everything. I wouldn't be here without them. I like to refer to them as my ride or die fam.

But we're all experiential learners to some extent. And it didn't help coming from public high school and then going to Stanford. Like, I had never gotten a B on an English paper. Ever. And I just went into office hours to talk to the professor. I think about this now and the hubris. But he says, "Ah, your first B," but that also has a lot to do with the school population. I think my challenge was always to do my best and respect that my best was my best.

C: That's what you can do, right? With the resources that you have. In terms of the support that your family was able to give you, do you think that being a first-gen student, with them not going to college, was there any disconnect when you tried to talk to them about higher education? Were there any miscommunications along the way?

B: Of course there were. But I was lucky in the fact that I have five sisters. A big Catholic family. And so my older sisters took different routes to higher education, sometimes through JCs, sometimes through work, and then going back to school, so there wasn't the “usual” path. But because my older sisters are, you know, eight to 14 years older than I am, there were other translators who could understand the process.

I think my mom would have preferred me to be a lawyer, rather than first a teacher, and then a professor. I don't know if it was preferred, but she always used to say (she passed away this summer) "Always thought you'd be a lawyer." But I think that's also about an understanding of what's valued for education. Does that make sense? Doctor, lawyer, chemist and engineer. Those are very clear paths. And God knows academia is not. You can be an absolutely phenomenal graduate school student and end up doing the freeway adjuncting. I was just very, very, very lucky to get the job in Michigan. And I got tenure there. And it only took me 16 years to get back to California, where I'm from. But that was a big goal to get home.

C: I guess in terms of growing up with those pressures to possibly go into what some people might deem a more socially acceptable career, how were you able to discover your interests and find out what you were passionate about? And then land in academia?

B: I went away to school. That was part of it. I changed majors...four times? Originally, I wanted to be a human bio major to go the pre-med route. Because I had had all the health issues, I wanted to become a surgeon.While in Calc 41, I realized: A) it wasn't me. I'm a humanities girl through and through, and B) because of earlier health issues, I had lost sight in my right eye and you can't be a one-eyed surgeon. And so human bio was off the list. Then it was journalism, and at Stanford it was communications. Really, because I ended up interning at a paper, but I'm not a fast writer. I craft, so things can go at the speed of an Icelandic glacier before global warming. So that wasn't it. Then, creative writing, which I really loved.

A Commitment to Public Education

B: I was going to school during the end of the Cold War, so I was fascinated by American history. But that would be five times I changed my major. I ended up being an American studies major, which means you could construct. You take pieces of what you found interesting. My focus was actually on post-war history. It just sort of evolved from the opportunity to recognize that the path I had set for myself was not me. And to be honest, there wasn't pressure to be conventional.

And then in my senior year, I was getting ready to take the LSATs, because that's what you do. I heard a lecture by a person who talked about how the failure of public education is people who have benefited from public education who don't give back to it. And it was so moving that I put in my application for the Stanford Teacher Education Program (STEP) later that same week, because I know that public education is so important for folks like us. And we've watched it be systematically gutted over the past 25 years. I felt like it was my responsibility to give back. And so I got a teaching degree and M.A. in education. And I was a high school history teacher for eight years, teaching American history. I sort of mitigate this by saying that I ended up getting a job at a very progressive, very well-funded high school in Massachusetts. It was an interesting experience. But it definitely wasn't the experience I think a lot of public school teachers have, because there was money. And I chose A People's History by Howard Zinn as my 20th-century United States history book. And there was no blowback at all! It was just a very different experience.

C: Was the idea of moving into higher education developing while you were teaching high school? Or did you decide a bit later on?

B: I think I was moving that way. I think I liked the idea of creating a curriculum and doing stuff that didn't fit into boxes. My book Laughing Mad: The Black Comic Persona in Post Soul America was not my dissertation. I ended up, for a number of reasons that had a lot to do with post 9/11 sentiments, writing a brand new book in my first years as the assistant professor. This is something I would not recommend, particularly not in a place where there's a lot of pressure about tenure. They make you very scared. And the reason I mention it is that there’s a more vibrant humor studies, comedy studies, space in film and media studies now. I was able to forge a road into it. And it's interesting to talk to people who do that work now, almost 15 years later, and say, "Oh, yeah, that was a seminal book that helped me think about it."

Yeah, these were questions that I had asked myself when I was trying to teach about racism, and about sexism, and all the way back in American issues and, you know, in the early 90s. And I believe that teaching is a vocation, not a profession. And because of health issues, having not been able to teach, having been on leave, this quarter was just a joy. Being in the classroom teaching a small class on black TV comedy. It's wonderful watching those light bulb moments when you see somebody get it. And yeah, teaching isn't what I do. It's who I am. This is why I tell students, "Come into office hours. I'm not scary." Please! This quarter, I made it mandatory. You had to come into at least one office hour, because I had incredible professors that I was too scared to go in and see (when I was in undergrad). I wanted them to know that I cared about their education. And I do mention that I'm first-gen in classes. I don't have to mention that I'm Black and a woman because that's obvious. But I do mention that I was a working class kid. Because sometimes just the idea that somebody else actually could do it is a big deal. It's just gotten progressively more expensive for students. I didn't pay off my Stanford M.A. until I was an assistant professor at the University of Michigan. I do not face student loans like folks face now. But I was in my late 30s and early 40s when I finally paid it off. And that was just for the M.A. program. Student debt is a huge deal. And having the pressure to figure out what you want to do is also very real.

C: To make their education worth it in a lot of ways.

Gig Economy and the Side Hustle

B: Since you folks have grown up in a gig economy, people may have more than one job. The idea of a side hustle is common. If you're fortunate enough to have work study, or some kind of campus work, you may still need to have a side hustle, in order to pay the bills. Those are very different pressures than what a lot of students have to go through. And I think those are things that first-generation students have to face. When I was getting my M.A. – this will sound absolutely ridiculous – I was able to get a job that paid pretty well. My job was to ride around campus and deliver those big envelopes. I was also student teaching, doing coursework. It was a lot. And that's when I was finishing up. When you're doing a doctoral program, it's different. You might be fortunate enough to get fellowships, but a great fellowship, a fellowship in Iowa that's the same amount as a fellowship in Los Angeles, is not the same amount of money.

C: Right, in terms of cost of living, and all of that combined.

B: So even if you have a ride, you're gonna have to take out some loans, or you're gonna have to do some kind of a side hustle. For part of the time I was in graduate school, I worked at the Ice House, which was a comedy club. Just nothing exciting. I worked in the booth or wrote press releases and did telemarketing. Undoubtedly, that had an influence over the work I did. I think there's an advantage to the disadvantages: because at the same time that they can weigh you down, they can also give you a resilience that other people just don't have. Like, the only metaphor I can think of right now is very personal. I've had a lot of neurosurgery. And part of the issue has been about pressure on the brain. And your dura, which protects the brain, has been challenged many times in the past five years. But the dura toughens up. You know, it gets thicker, gets stronger. And I want to get this t-shirt that says "My dura is the boss." Because the fact that I'm still here and functional is pretty amazing. But I think our experiences are like our dura. You don't want anybody to have to live through traumatic experiences. But sometimes it takes traumatic experiences in order for you to find a strength that you didn't know you had.

My pop, who was my world and my everything, died the month before I started the Ph.D. program. I was a ridiculous mess. The professors who would become my advisors, one became a surrogate brother and the other became a surrogate dad. But I reached (going to office hours!) I reached out to them, and let them know what was going on. And having those spaces is also really important. Sometimes problems can't be solved, they are what they are. But knowing that there's someone you can talk to is important.

This is generalizing: but a lot of folks who are first-gen (and who are members of marginalized groups) haven't been raised in a culture where therapy is necessarily the first place to go. And I'm not a therapist, but I can listen, and I can encourage you. There is help out there. More accessible help now than there was before. I just feel like it's our responsibility. I want to know, or feel that all the blessings that I've been given, from my family to having had the health care I've had – because that's a huge deal – allow me to give back.

Self Expression in a TikTok World

C: Would you say that students today are still facing a lot of obstacles that you faced as an undergrad, as well as into your Ph.D.?

B: I think they're facing different challenges. But a lot of these challenges have to do with what's the emotional resonance of them. Around identity. Around belonging. Around "What do I have to say? What do I have to contribute?" And there are so many ways that people can express themselves, from TikTok to Instagram, Instagram Live, YouTube. You know, if you told me 20 years ago that there would be a job called “influencer,” it wouldn't have made any sense to me. I think it's about getting your brand out there and being seen, and unless you have a team who's helping you, I'm not sure that you always present yourself in the way that you want to. And I'm not talking about respectability politics. I don't want to limit expression. I think that your self reflection doesn't have to be in your Instagram story. And part of it's just generational. There are things that people talk about so casually on TikTok. And it's like, "You know, this is always gonna be here, right? You know, the internet is forever, right?"

In my experience, you're going to try a lot of things that don't end up being you. And some parts of those experiences will yield things that shape you for the rest of your life. You can learn from everything. But you've got to be willing to learn.

C: Would you say that that's something that you wish you would have said to your past self as well?

B: Oh yes. I look back at me in college and think, "Oh my Lord." Well, part of it led to getting married at 23, which I think no one should ever get married until 30. But a lot of it has to do with not having a sense of self and not having embraced the things that were scary. But we have all made decisions that we look back on and say, "What were we thinking?" You're gonna make mistakes. But I think what I would have wanted me to ask me is "Why? What's your motivation here? You know, are you acting out of fear? Are you acting out of complacency? You know, why?" I think there's a pressure to act, to know what's coming next. And sometimes you just got to sit with it.

C: Are there any final comments or pieces of advice that you would like to give before we close up?

B: Don't give up. Ask for help. And you are exponentially stronger than you know.

C: Thank you for sharing your first-gen experience with me, as well as the UCI community. I think you brought up some really important messages in terms of resilience and pushing through in times where things might feel confusing and very turbulent. But that's a part of self discovery in a lot of ways. And I think that's really the core of the first-gen experience. Just because we are going through this, this path that nobody else in our family has gone down before.

B: Oh, one last thing. Failure is only failure if you don't try again. You can't fail if you keep going. That's just a learning experience. Because I think that's a word that's really hard for first-gen folks. And it kind of doesn't exist. If you learn something from it, and you're going to take something from that to keep moving forward, that's a speed bump. It wasn't a roadblock.

C: No worries at all! I think they're very relevant. I think they really tie in with the first-gen experience. And yeah, failure is not an ultimatum. Perhaps it's just another opportunity to grow, to learn and navigate that path and possibly pass on advice to future generations as well.

B: Being able to give that back.

C: Thank you so much.

B: You're so welcome. Thank you so much.

Chloe Vo (she/her/hers) is a second-year undergraduate student at UC Irvine, majoring in Asian American Studies. Currently, she volunteers as the High School Outreach Coordinator for UCI’s Southeast Asian Student Association (SASA), teaches English at a local tutoring center, and works with a local social justice organization called VietRISE.