By Lisa Fung

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, David Theo Goldberg was focused on feelings of dread.

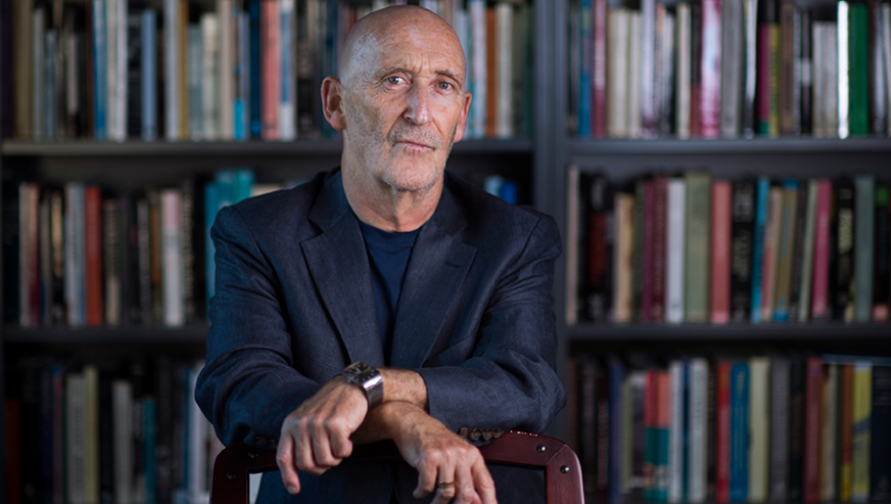

For Goldberg, Distinguished Professor of comparative literature and anthropology at the University of California, Irvine and director of the UC Humanities Research Institute (UCHRI), dread appeared to permeate more and more aspects of life, and he was curious to know why.

“Like all of us, I was waking up in late 2016 and the beginning of 2017 with a really tightened solar plexus,” he says with a laugh. “I was trying to put my finger on it. I knew what the external conditions were, but I was trying to put my finger on the conception that would give that a kind of palpable sense.”

During a morning swim, he began reflecting on those feelings, which led him to seek out intellectual literature about dread. Surprisingly, he found little.

“There’s obviously Kierkegaard and Freud, but in terms of contemporary critical theory, there’s very little – nothing that was spelling out conceptually what this condition was,” he says. “So, I started thinking more sustainably: What is it that is producing this? Obviously, you can point to the craziness around the presidential election of 2016, but it struck me as a more enduring systemic condition.”

The result of his extensive research is a new book called Dread: Facing Futureless Futures (Polity, 2021). The book opens by defining the concepts of dread, fear and anxiety, then offers a global perspective on the causes for its pervasiveness and finally suggests potential solutions. The centerpiece of the book focuses on “tracking-capitalism,” the collection of personal data for financial gain and political control, as a root of dread.

Though Dread deals with concepts of critical theory, its pop-culture references and personal stories offer relational ways of thinking that make it accessible to non-academics. The serendipitous timing of his writing allowed him to include a look at the COVID-19 pandemic – something any reader in any part of the world can relate to.

“As soon as COVID hit, I knew there was something there,” he says. “It was obviously feeding the already-paranoid condition that we were in. There’s no way you can write a book on dread today without writing a chapter on COVID.”

Goldberg is a world-renowned expert on critical race theory, which emerged as an analytical framework in the legal academy in the 1980s to challenge deep-seated assumptions that the law is neutral and necessarily just. At the same time, critical theoretical work on race was opening out across the human sciences to address the ways racisms have been systematically structured into state and social institutions as well as pervasively culturally expressed. Nevertheless, Goldberg intentionally avoided a separate chapter about race in his new book. “Today, that might be different, given the explosiveness of the moment,” he says, referring to the debate over whether critical race theory should be taught in schools, “but I wanted to thread race into all aspects of life because it is part of all aspects of life.”

With his ready laugh and easygoing demeanor, it’s sometimes easy to forget the serious nature of Goldberg’s research. Race and racisms have been a part of his consciousness for his entire life. As a young boy growing up in Cape Town, South Africa under apartheid, Goldberg, who is white, attended segregated schools, surfed on segregated beaches and swam in segregated pools. But there still were daily interactions, whether with his friends or the people who worked in his family’s home.

“That contrast between that apart-ness, that distance, that segregation and that intense closeness – you can’t help but be shaped by all of it,” he says. “What interested me from my teenage years onward was that you can’t be that close with people and not be engaged with them and not find richness in life from that engagement – in all aspects of life.”

His early inquisitiveness signaled what would eventually become his field of study.

“I was always the ‘why’ kid, I was always asking my parents why this, why that and driving them nuts,” he says, chuckling at the memory.

By the time he was attending college at the University of Cape Town, he was committed to philosophy.

“I actually was expected to go into law or become an accountant. My brother was already doing medicine, so the next kid needed to be doing something else professional,” he says. “I made a deal with my father after my first year: I could drop out of business and take philosophy as long as I continued in economics. It was wise because it was an interesting intellectual project, which I probably wouldn’t have otherwise pursued.”

After he finished his degree, he took a year off to pursue another lifelong passion: surfing. “I put a backpack on my back and two surfboards under my arm and went island hopping through the Indian Ocean, surfing my way to Australia,” he recalls.

Later, he returned to Cape Town to pursue two graduate degrees in philosophy, then traveled to Europe to figure out where he would complete his doctorate.

“I was hanging out at universities in Britain, and I got a number of offers from American universities,” he says. “My oldest and closest friend was already in New York; he was at Columbia studying filmmaking. He kept on calling me and saying, ‘This is the place, come on over.’”

Lured to New York not only by his friend but also by fellowship opportunities, Goldberg began graduate school at the City University of New York and settled into the art scene with his filmmaker friend, Michael Oblowitz, and another longtime friend from South Africa, Anton Fig, who would later become the drummer for David Letterman’s band. During this time, Goldberg and Oblowitz began talking about making a film together about South Africa.

“It was a very experimental film. We got our hands on a documentary that had been made by the South African apartheid government to promote foreign investment in South Africa,” he says, laughing conspiratorially. “We ended up cutting it up – literally cutting up the film and using some of the footage as a way of deconstructing the argument that was being made that Black and white people were living happily together in South Africa, that Black and white kids were in the same classroom and so forth.”

Completed with computer graphics, split screens and cutting-edge technology of the time, Goldberg and Oblowitz showed the film, “The Is/Land,” at a number of national and international film festivals, picking up awards along the way.

Riding on the success of the film, they raised money and launched a small film company called Metafilms. By day, Goldberg was working on his doctorate and at night creating films and music videos, including Kurtis Blow’s “Basketball,” an early rap song featured on MTV.

“I was literally on film sets until five in the morning and then teaching Descartes at 9:00 a.m. at NYU,” he recalls. “I had to ask myself what do you really want to do? Do you want to produce movies? I really wanted to be an intellectual, an academic.”

Goldberg’s path to UCI came via Drexel University and Arizona State, where he quickly became a full professor and director of the School of Justice Studies. He remained at ASU for a decade but spent a year at Berkeley starting in 1998. There, he reconnected with an old friend, Angela Davis, whom he had first met while in New York and then again while speaking together on panels at conferences. Davis was just co-starting Critical Resistance, the prison abolition organization, and enlisted Goldberg to help with some of the activities.

The following year, Davis established a residence group at UCHRI on California prisons that included noted scholars from across the country. She invited Goldberg to join, so he commuted back and forth from Arizona. By chance, UCHRI was seeking a new director, and Goldberg was encouraged to apply.

“I actually really wanted the job,” he says, laughing. “California is like Cape Town. I was right at home, right away – I could surf.”

When he took over as director, Goldberg inherited a humanities institute with a largely national focus for the then-nine (now 10) UC schools. The institute, established in 1987 by UC President David Gardner, was ready to broaden its presence on the world stage, and Goldberg looked to infuse some of his personal experience into the mission.

“For me, the driving issue of the humanities has always been the changing nature of the human, the changing condition of what it is to be human,” he says.

Race and racism continued to be central interests for Goldberg, but he began to look outside the U.S. to develop a more global perspective. By tapping into his wide range of contacts, he looked to expand the reach of UCHRI, giving it an international face beyond the standard European connections, to Asia and the Pacific Rim, Africa, and Latin America as well.

“If I have stood for something, it’s a kind of globalization of UCHRI,” he says.

Goldberg began a summer program beginning in 2002 at Irvine, drawing on notable people from the UC system and nationally. “Then we took it on the road and did five internationally,” Goldberg says. “We did one in Hawaii. We did one in Beirut. We did a massive one in South Africa.”

The summer school in South Africa in 2014, called Archives of the Non-Racial, involved a two-week bus tour through major sites of the anti-apartheid struggle, starting in Johannesburg, moving on to Swaziland, where the ANC in exile was centered, down to Durban, where the 1973 labor strikes occurred, on to Mandela’s burial site, where there is now a writing retreat, through Port Elizabeth and on to King William’s Town’s Steve Biko Center for Black Consciousness and finally ending in Cape Town.

“It was amazing,” he says, smiling at the memory.

During his tenure, Goldberg also secured more than $100 million in funding for the UCHRI through grants from the MacArthur Foundation, the Mellon Foundation, the Hewlett Foundation, UC-wide competitions, and others.

But in a surprise move, Goldberg recently announced that he plans to step down in a year’s time.

“It’s time for younger energy, I think, to step in and step up and take a different direction, define it differently, figure out different relations for the University of California,” he says.

Once a new director is named, Goldberg plans to take a sabbatical – his first in 22 years. He plans to write a “memoir of my generation,” he says, writing about South Africa through the lens of his own life.

“I grew up under apartheid South Africa and then left before the end,” he says. “They were extraordinary times. I’m thinking I can use it as a story to speak more broadly about a generation and its shaping.”

Officially out July 6, 2021, Dread: Facing Futureless Futures is available from Polity Books (use code POL21 for 20% off on the paperback edition through 12/31/2021), Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Brookline Booksmith, and Wiley.

Photo credit: Steve Zylius/UCI