By Lilibeth Garcia

When Seungyeon Gabrielle Jung, assistant professor in the Department of Art History, wants her students to grasp the way design impacts everyday life, she points to the American highway system. They don’t have to think about it too much. The mental image of a morning commute creates a visceral understanding.

It’s also a visual that helps illustrate what Jung refers to as “design as a problem-solving method.”

The interstate highways that weave in impressive geometric configurations help eliminate traffic in densely populated areas and make transportation more efficient, but they also segregate communities and make walking challenging.

This complexity is what Jung looks for in her research: “I question, what does design do? I'm interested in the doings of designs – design as a verb,” she says. She also studies how, in the process of solving a problem, design often becomes problematic. “Design is actually very good at creating problems, and when it comes into material existence, the problem stays around for a very long time.”

A wide range of things are carefully designed, including product packaging, kitchenware we use on a regular basis, language systems we write in, even the pop groups we listen to. However, despite the ubiquity of design and its long-lasting, all-encompassing influence, design history is a rare field of study in the U.S.

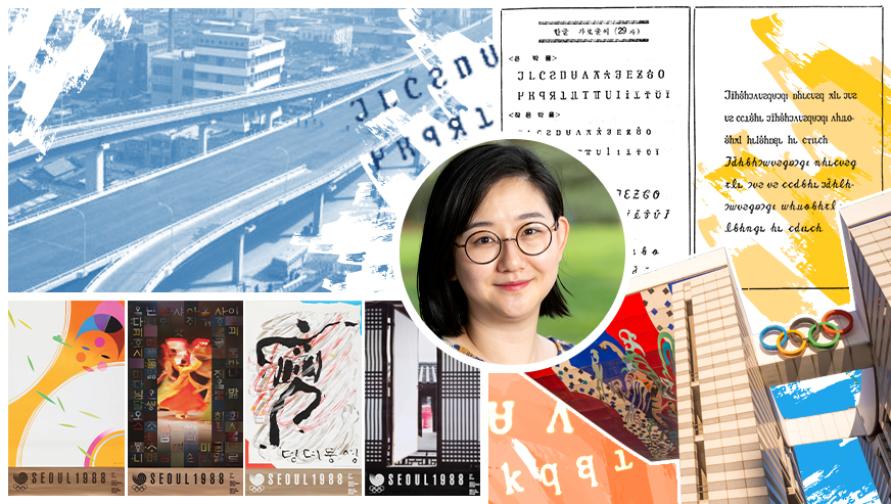

Even rarer is the merging of design history with East Asian studies and media studies. Jung – who received her Ph.D. in modern culture and media from Brown University, and M.A. and B.A. in English, as well as B.F.A. in visual information design, from Ewha Womans University in Seoul, South Korea – overlaps various subjects to examine design in the developmentalist and post-developmentalist contexts.

“First world designers were often brought into third world countries, such as India, Turkey and South Korea, to solve economic and social problems. Design was used almost as a propagandistic tool,” she explains. “The so-called developed countries, which had the design power, saw the developing world as a bundle of problems to be resolved by Western technology and design. But if we think about it, design has always existed in every culture, and there are different ways to design. Defining the practice as a mere problem-solving method limits our understanding of design.”

Modern design in South Korea

Jung’s book project, “Toward a Utopia Without Revolution,” looks at the political and aesthetic problems that modern design has created in South Korea. One of her chapters dives into the 1988 Olympics, which was held in Korea as it recovered from a series of dictatorships, the Korean War and Japanese colonial rule.

South Korea was the third country to host the Olympics that wasn't in Europe or America, making the games an optimal opportunity to present itself as a modern nation on the international stage. But to do so, it had to design a visual identity for itself, a challenging feat after a tumultuous history of cultural erasure.

The South Korean government had forcefully eliminated many of the traditional religious symbols – which were deemed primitive and superstitious – from the country’s landscape in the 1960s and 70s. When the state was preparing for the Olympics, it couldn't figure out what was uniquely Korean, so it had to resuscitate the “relics” it had once destroyed.

“Because they were very hastily and unthinkingly recuperated, they ended up orientalizing Korean culture for the global audience,” Jung says. “They were empty symbols. They were symptomatic of the modern Korea that the dictators wanted to sever from the ‘backward’ pre-modern nation that Korea had once been.”

Through her design research, she gets to the root of what it means to construct “Koreanness” and what “Koreanness” entails.

Another example she looks at is the Korean writing system. Korean typography has evolved from vertical writing that mixed Hangul (the Korean alphabet) and Chinese characters to horizontal writing with no Chinese characters. Some linguists attempted to redesign Hangul so that it emulates the Roman alphabet and adapts better to various printing technologies such as typewriting.

“But what came out of this experiment was badly mangled Hangul that lost all of its grace and beauty,” she illustrates. Hangul typography has continued to evolve and improve thanks to the work of contemporary designers.

The design of K-pop

While Jung traces, analyzes and critiques Korean legacies, she also looks at emerging trends in Korean media. Interest in Korean culture has grown exponentially over the past decade thanks to the explosive popularity of K-pop and K-drama – two genres that are heavily and meticulously designed for global consumption.

The up-and-coming K-pop girl group NewJeans is produced not by a music producer or a composer – but a graphic designer, Min Heejin. She directed the visuals for a number of K-pop groups and has received critical acclaim for her work on idols such as Shinee, f(x) and Red Velvet. NewJeans is the newest addition to Min’s portfolio, and her success attests to the importance of design in K-pop and Korean culture.

Many of Jung’s students are well-versed in Korean pop culture trends, making it an accessible topic to discuss the effects of design. “It's kind of amazing to see. My students already know a lot about Korea and Korean design because they consume so much of the Korean cultural product,” she says.

In one of her design history classes, she gave students the option to choose the topic they would study for the final week of the course, and they chose plastic surgery – a common undertaking among K-pop stars and a clear example of design as problem-solving.

They spoke about K-pop idols’ skin-lightening and even Ariana Grande’s recent make-up choices. The class discussion included a brief lesson on pre-modern Korea and its preference for lighter skin because it signified having a high social status and not needing to labor under the sun.

“Bringing all these different pieces of the puzzle together and having a productive conversation is what I look forward to in my classroom,” she says. “That’s the beauty of teaching design. We live in a world where everything is designed, so students come to class with extensive knowledge on the subject. My job is to provide frameworks that help students think critically about their worldview in addition to the course materials. One of my students told me that my course made them think critically about everything around them. I took that as the highest compliment.”

Expanding the definition of design

Design doesn’t always have to solve problems. “It can just be beautiful,” Jung says. “It doesn't even have to have a purpose. I'm actually more interested in ugly designs because what we think of as good design is itself very problematic.”

The “bad designs” of developing countries were often seen as such not because the designers weren’t talented, but because they didn’t have the means to live up to the “good design” standards of the West, Jung explains. And sometimes bad design is a necessary step to truly effective and beautiful design.

“I'm really interested in bad designs that don't work or misbehave. Good designs are barely noticeable because they work so well, but bad designs hit you in the face. That’s when design makes itself known, and that fascinates me,” Jung says. “Also, design is not just one thing: It can be beautiful. It can be ugly. It can be good. It can be bad. It can be a lot of things at once. What I’m interested in is complicating the understanding of design and not just putting certain objects into certain boxes.”