By Nikki Babri

Before the 1990s, Asian American literature was a niche genre, with relatively few novels readily available for readers. At the time, scholars could claim to have read the entirety of Asian American literature. Today, however, with its remarkable growth, that would be impossible.

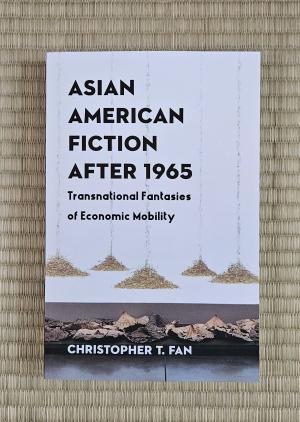

Asian American voices have become increasingly influential and diverse in American literature, offering narratives that deeply resonate with the immigrant experience. A significant contribution to this evolving conversation is Christopher T. Fan’s book, Asian American Fiction After 1965 (Columbia, 2024), which offers a nuanced analysis of the intersections of class, race and identity within this literary landscape.

“In terms of the Asian American novel, I’ve observed two major trends. First, it’s been booming since the 1990s. This continuing boom is accompanied by the mainstreaming of Asian American literature. We’ve seen this with the high-profile success of novels like Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko, Ling Ma’s Severance, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer and Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown,” shares Fan, an associate professor of English, Asian American studies and East Asian studies. “The second trend is that, compared to just a few decades ago, Asian American novels are increasingly interested in exploring Asian histories and identities. Scholars have called this the ‘transnational turn,’ which I think will continue.”

At the heart of Fan's research lies a fundamental question: What does it mean for an Asian American author to be from Asia?

The rise of Asian American literature

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act fundamentally altered the demographic landscape of the United States, opening its doors to a large number of immigrants from Northeast Asian countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, Japan and China. Fan writes, “As a direct result of the act, the Asian American population has increased by a factor of nearly thirty, making it the fastest growing ethnic group in the United States.”

As these new immigrants and their descendants began to come of age in the 1990s, a surge in Asian American literary output followed. This period marked the emergence of what scholars refer to as “the children of 1965.”

This wave of immigration included many highly skilled professionals in fields like science, technology, engineering and math, which influenced the professional and educational aspirations of their children. While researching, Fan was surprised to learn that before the 1960s, the most popular college majors in Northeast Asian countries like South Korea and Taiwan were in the humanities and social sciences, and there was a general reluctance among students to train in scientific or technical fields.

The shift toward STEM fields was driven by state policies in these countries, aimed at supporting rapid industrialization. “We have this stereotype in the U.S. that Asians are somehow naturally good at math and science. But the reason we think that is because many of the immigrants from Northeast Asia after 1965 were students who came for advanced training and professions in math and science fields,” he explains. “Even in their sending countries, it was the strong hand of the state that guided them into those fields in the first place.”

Much of Fan’s interest in the topic comes from navigating conflicts with his own parents when choosing his professional direction. He grew up in Houston, a major center for the oil and gas industries, and home to NASA. His father was a mechanical engineer while his mother was trained as a biologist. “And yet I went into literary studies,” he shares. “I think much of what went into this book was a personal desire to understand how this apparent contradiction or divergence between the sciences and arts is actually false, and how the professional decision between the sciences and arts, for many post-65 Asian Americans, is actually the same decision.”

A fresh perspective

His inspiration for the book stemmed from a conversation with a fellow scholar of Asian American literature about the Taiwanese American science fiction writer Ted Chiang, which sparked his realization that the essence of Chiang's Taiwanese American identity lay beyond racial or national labels. Instead, it was rooted in historical developments and professional trajectories typical of many Taiwanese Americans who pursued advanced training in STEM fields after immigrating to the U.S.

“We need to think about Asia and the relationship between Asia and America through history. The lenses of geopolitics, political economy and demographic trends reveal the material and ideological forces that Asian American authors contend with – not only in their writing, but also in their very choice to become an author in the first place,” Fan says. “These forces reveal the complexities that those authors are unpacking: namely, what it means to be Asian American in a historical moment when Asia, especially China, is so ascendant in American life that it’s reshaping the very category of Asian America.”

A prominent theme Fan explores is the intergenerational conflict that shapes the narratives of second-generation Asian Americans. Turning to the works of authors such as Chang-Rae Lee and Kathy Wang, Fan examines the tensions between parental expectations and individual aspirations, highlighting the struggles faced by the children of immigrants in navigating their own identities and futures.

This dynamic can be seen in the academic journey of novelist Maxine Hong Kingston. When Kingston started at UC Berkeley, she intended to be an engineering major and had an impressive eleven scholarships to support her, but abandoned it all for an English major. Fan shares how this choice shapes her writing, especially her book Woman Warrior, which he admits took him some time to appreciate. “I love it now because approaching it as a document about the historical processes and tensions I’ve described have revealed so many of its overlooked dimensions to me – for instance, the drama of her mother’s deprofessionalization after emigrating to the U.S., and how that disappointment shapes her relationship with her children,” he says.

Fan also analyzes the conflict between the arts and sciences in Asian American fiction. He observes how this tension mirrors broader societal expectations and professional paths, becoming explosive when a parent's devotion to a STEM career clashes with a child's differing ambitions. This, he argues, has left a lasting impact on the self-consciousness of Asian American writers, who often find themselves at the intersection of technological advancement and creative expression.

Future directions

Currently, Fan is working on two books – one examining the trope of China’s rise in fiction and film, while the other provides a cultural history of semiconductors that doubles as a contemporary history of Taiwan. And despite describing himself as “pretty bad” at creative writing, he reveals his ongoing fantasy of writing a novel or rekindling his love for playwriting.

Fan is hopeful that this book will encourage readers and students to push beyond identity and recognition as the goals of their research, writing and activism. “It’s important to express oneself confidently as an Asian American, and to know the history of those expressions. I am here in this profession, and my book is possible because of generations of brave people before me who have translated those expressions into institutional spaces like Asian American studies.”

He warns, “But if you stop at identity and are satisfied with recognition, then you sacrifice broader visions of social transformation.”

Interested in reading more from the School of Humanities? Sign up for our monthly newsletter