By Nikki Babri

In a world that often seems fragmented and dispersed across the countries, languages and cultures of the world, there is a powerful force that transcends such boundaries: cinema.

Within UCI’s School of Humanities, students quickly learn that films are more than just entertainment; they also enable us to cross borders, connect diverse histories and explore complex geopolitical issues. This fall, for example, students are learning about the iconic martial arts mastery in “Bruce Lee,” the unparalleled emotional storytelling in “Korean Cinema” and the dazzling world of vibrant dance routines in “Bollywood Film: Gender, Sexuality, Nation.”

A collaboration between humanities departments, including film and media studies, Asian American studies, East Asian studies and global cultures, these courses encourage students to examine how films become the vessels for understanding an interconnected world.

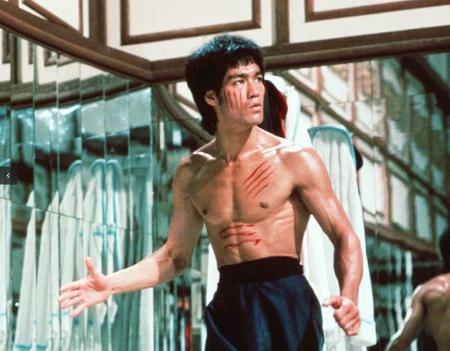

The Bruce Lee phenomenon

Bruce Lee, an icon who transformed martial arts and cinema, is the enigmatic and eponymous subject of “FMS 130/GLBLCLT 103B: Bruce Lee.” This course invites students to journey through the life, work and enduring influence of a man who, from his humble beginnings as a dishwasher in a Chinese restaurant in Seattle to his becoming a global superstar, reshaped worldwide cinema and culture.

“Bruce Lee is a classic case of a celebrity who is universally known but poorly understood,” says Glen Mimura, an associate professor of film and media studies. “I love his films, find his life story endlessly fascinating and thoroughly enjoy introducing students to both.”

Bruce Lee did more than just entertain; he challenged stereotypes for Asians in Hollywood and redefined the action genre, extending the reach of cinema as an international medium. “Although Hong Kong martial arts films already enjoyed global circulation in diasporic Chinatowns, Bruce Lee’s films catapulted the genre’s popularity into virtually every established and emerging film market,” Mimura explains. “Enter the Dragon,” a Hollywood-Hong Kong co-production, marked a turning point, propelling the Hong Kong film industry to global prominence and paving the way for future martial artists and stuntmen like Chuck Norris and Jackie Chan.

This course blends film and media studies, Asian American studies and gender and sexuality studies – specifically the ways in which these fields engage issues of diaspora and transnationalism. Students gain further insights into the rise of Hong Kong's film industry and the counterculture and anti-racist movements of the 1960s and 70s. Watching Bruce Lee's films is just the beginning. The class encourages students to think critically beyond summaries and engage with scenes that reflect their own diverse backgrounds. They also reflect on their own connections to contemporary media, pop culture and social movements.

“Slowly unfolding, week by week, how in a dozen years Bruce Lee goes from being an anonymous nerd to the world’s most widely recognized and adored superstar is a sheer pleasure. It blows students’ minds,” Mimura says.

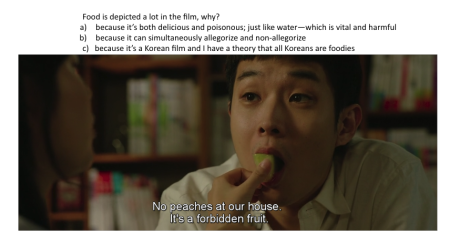

Exploring Korean cinema

Despite South Korea’s small landmass and population, Korean films (and music and television) have emerged as a global cultural force. “EAS/FMS 160: Korean Cinema,” offered by the film and media studies and East Asian studies departments, investigates the reasons why South Korea has become an entertainment giant, and helps students explore the historical, cultural and societal significance of this cinematic powerhouse.

“Korean cinema is perhaps the most important film and streaming industry outside Hollywood, in terms of its marketing value, global economic impact and aesthetical significance,” says Kyung Hyun Kim, professor of East Asian studies and founding director of the Center for Critical Korean Studies. “Over the past twenty years, I have personally witnessed its growth. Understanding Korean cinema helps better grasp the power of Korean culture – history, drama and even music.”

Kim’s course explores the profound influence of historical events on South Korean cinema, using recognizable examples such as the Oscar-winning sensation “Parasite” and Netflix’s most-watched show to date “Squid Game” (also see: UCI’s “Squid Game”-inspired games of red light/green light and ddakji) to go deeper than surface-level analysis and analyze the historical contours. Rather than merely classifying it as a black-comedy-turned-horror movie, students will discuss how “Parasite” provides a commentary on Korea’s division, the waning of Korea’s democratic movement and the fragility of neo-Confucian moral values.

The interdisciplinary nature of the class ensures students grasp the linguistic and cultural nuances that make the films truly come alive. It's a comprehensive approach that leaves no stone unturned (which, Kim admits, is why he always runs out of time in class), providing students with a strong understanding of South Korean cinema and its larger cultural context.

Clearly “Korean Cinema” isn't just about watching movies. Students are encouraged to abandon the habit of summarizing films and – similarly to “Bruce Lee” – engage deeply with the material, focusing on the scenes and moments that resonate with them personally. Establishing this point is, Kim believes, the first step in formulating one’s own critical perspective on self-identification and, subsequently, the relational foundation between ideology – including nation, race, class, gender and sexuality – and selfhood.

Unraveling the magic of Bollywood

Enter the captivating world of Bollywood, where dance, music and storytelling converge to create global culture. Taught by Beheroze Shroff, lecturer of Asian American studies, “ASAM 150/FMS 160/SOCSCI 179: Bollywood Film: Gender, Sexuality, Nation” eclipses the glitz and glamor to discover the complex layers of Bollywood, India's Hindi-language film industry. Shroff’s class uncovers how Bollywood, once confined to India and its diasporic communities, is now considered one of the largest industries in the world and has become a transnational force.

“My course focuses on Bollywood films made after the 1990s, when neo-liberal economics opened India to foreign investment and, with that, American lifestyles became popular in urban areas,” shares Shroff. “By the 1990s, Bollywood films were aimed at Indian audiences in global Indian diasporas. These films reflect a culture of nostalgia for traditions of the homeland left behind.”

Through the lens of Bollywood, students dissect how the industry reflects and refracts social, economic and political changes in India. From celebrating the self-sacrificing mother in 1957’s “Mother India,” symbolizing traditional family values and gender roles, to the 1995 film “Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayengey” (“The Lover Wins the Bride”), audiences observe a shift in the portrayal of female sexuality and desire in song and dance. Yet these expressions remained closely overseen by Indian men, preserving the traditional norms of female chastity and honor.

Bollywood appeals to global audiences through its vibrant storytelling and the universality of its themes. Drawing from social sciences and humanities disciplines, the course showcases how Bollywood films portray Indians living abroad, grappling with intergenerational dilemmas while maintaining ties to their homeland. “Students learn to subject popular culture to analysis, discovering that Bollywood cinema contests the view that India is an unchanging timeless country. They learn about India as a subcontinent with diverse languages, religions and regional cultures and, in the process, that Bollywood film is more than just entertainment,” Shroff notes.

All three classes exemplify the ever-evolving role of the humanities in understanding our interconnected world. Keep an eye out for further exciting cinema classes offered in the School of Humanities – open to cinephiles, casual moviegoers or students simply curious about the world.