By Nikki Babri

Nestled within the Black Panther Party's complex history, the Oakland Community School (OCS) stands as a foundational pillar of community engagement. Initially established as a community survival program of the Black Panther Party, the OCS boldly challenged traditional educational paradigms by providing academic opportunities to black and low-income children in local communities. Over 50 years later, its innovative curriculum continues to echo in modern educational practices worldwide.

The OCS inspired the creation of the Black Panther Oakland Community School Research Cluster (BPOCSRC), a collaborative effort launched in 2021 by the UCI Humanities Center and Angela LeBlanc-Ernest, a distinguished independent scholar, oral historian, documentarian and community archivist. Co-led by Judy Tzu-Chun Wu and scholars Tatiana Bryant, Desha Dauchan and Krystal Tribbett, the cluster’s mission is to recover, preserve and share the history of the OCS. Through 10-week paid summer fellowships, undergraduate and graduate students engage in research, archival practices, digital humanities and experiential learning.

“The goals of the Humanities Center are to spark knowledge by supporting research; foster vibrant intellectual communities; and inspire conversations that matter. This research cluster supports all three missions,” shares Wu, professor of Asian American studies and history, and director of the UCI Humanities Center. “The research cluster model and the team-format of the summer fellowships allow for opportunities to create meaningful relationships, especially for UCI graduate and undergraduate students to connect with scholars, activists and artists beyond the campus.”

LeBlanc-Ernest has conducted research on the Black Panthers for over 30 years. Initially started in 1966 by political activists Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale to protect black citizens from incidents of police brutality, the Black Panther Party went on to create over 60 survival programs dedicated to providing social services to the community. Through her extensive work on women in the Black Panther Party, LeBlanc-Ernest connected with Ericka Huggins, the former director of the Oakland Community School, and later began The OCS Project in 2017. The byline for the project is “Curate. Create. Collaborate,” LeBlanc-Ernest says, and UCI’s involvement through the research cluster fits all three Cs.

“The spirit of the project is one of collectivity and collective work – and that was intentional,” LeBlanc-Ernest explains. “It's a nice blend of faculty, staff, community and students. I like to take an intergenerational approach, because I want to remind students that collective work gets you farther faster.”

The world is a child’s classroom

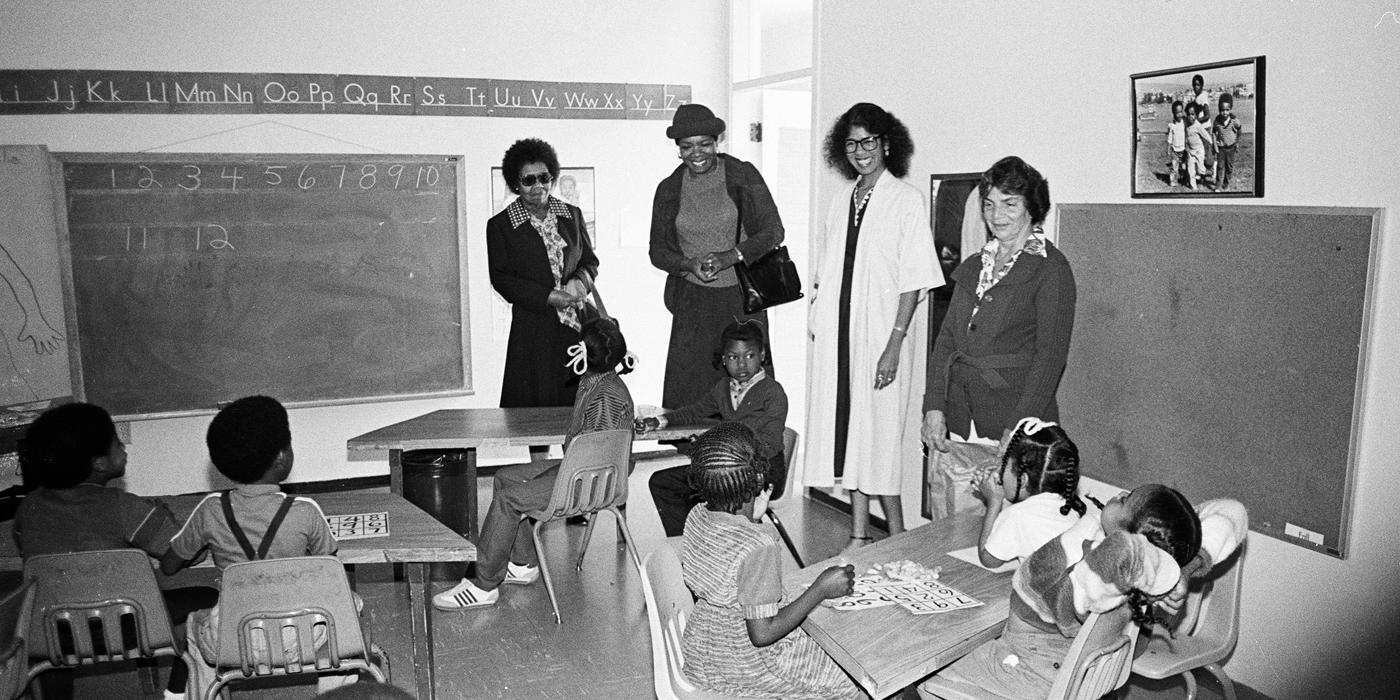

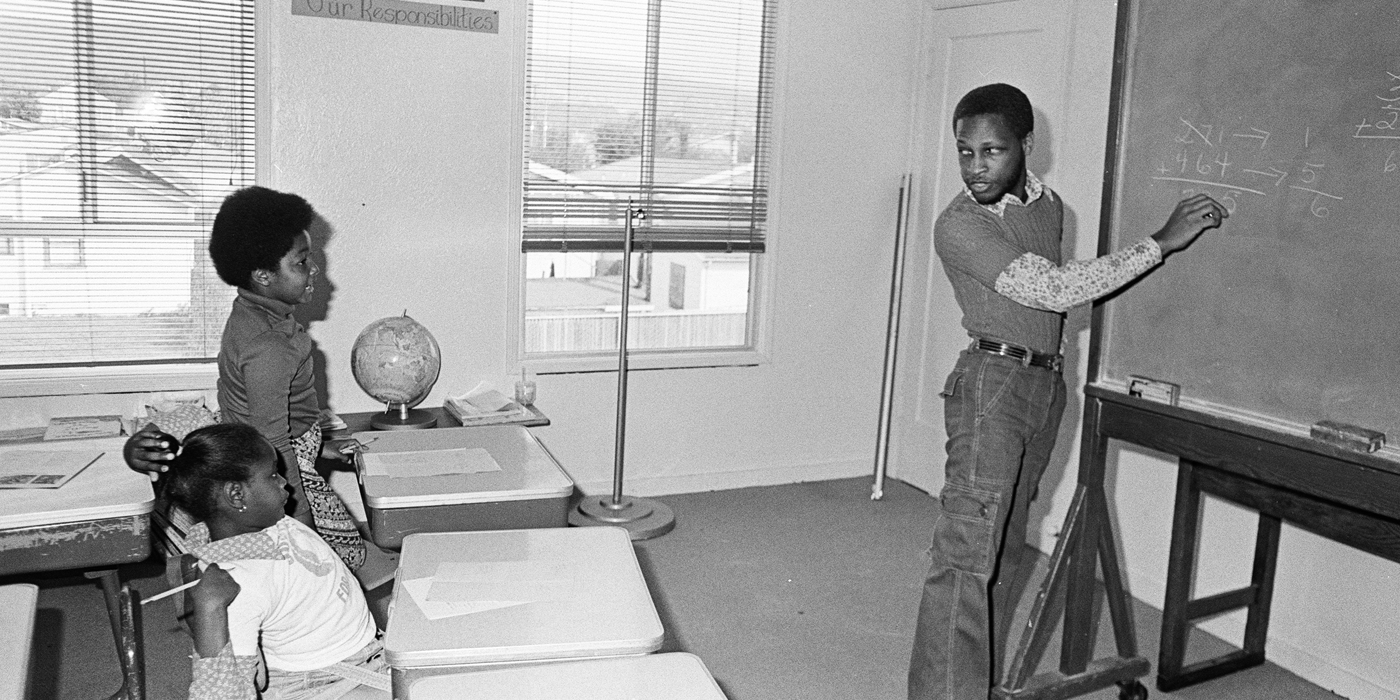

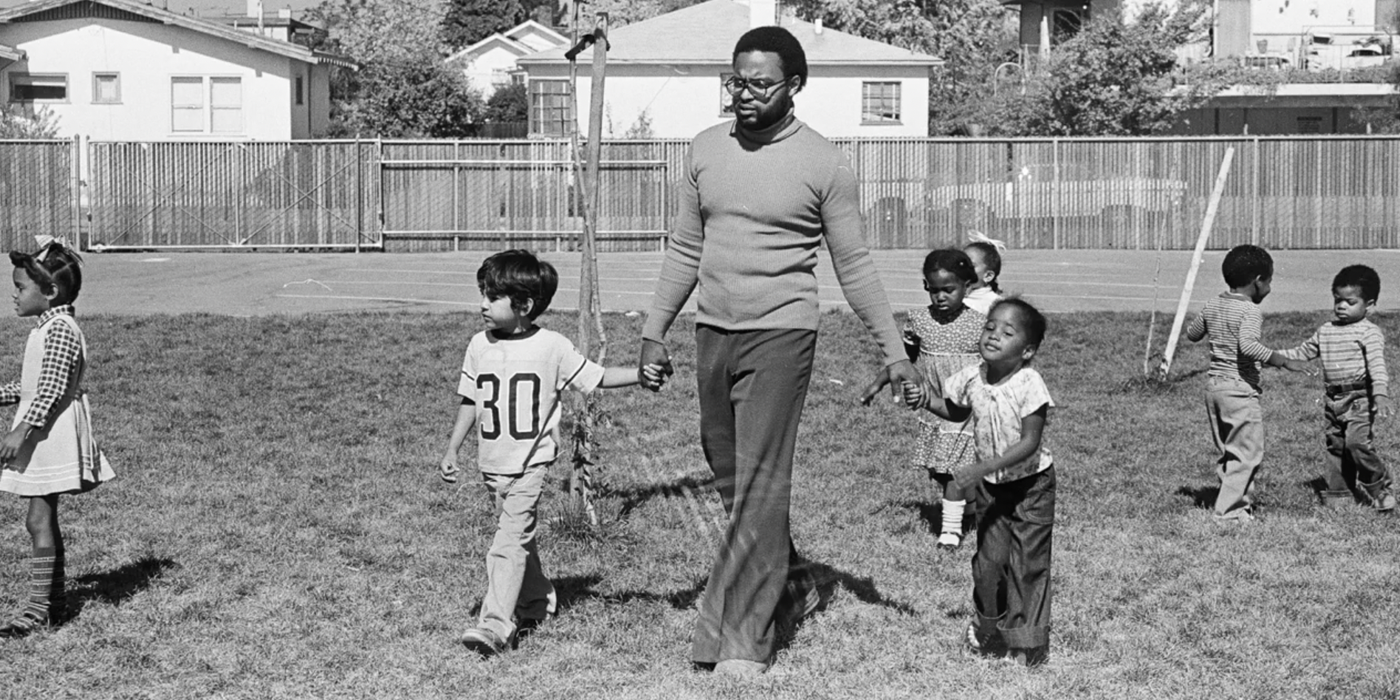

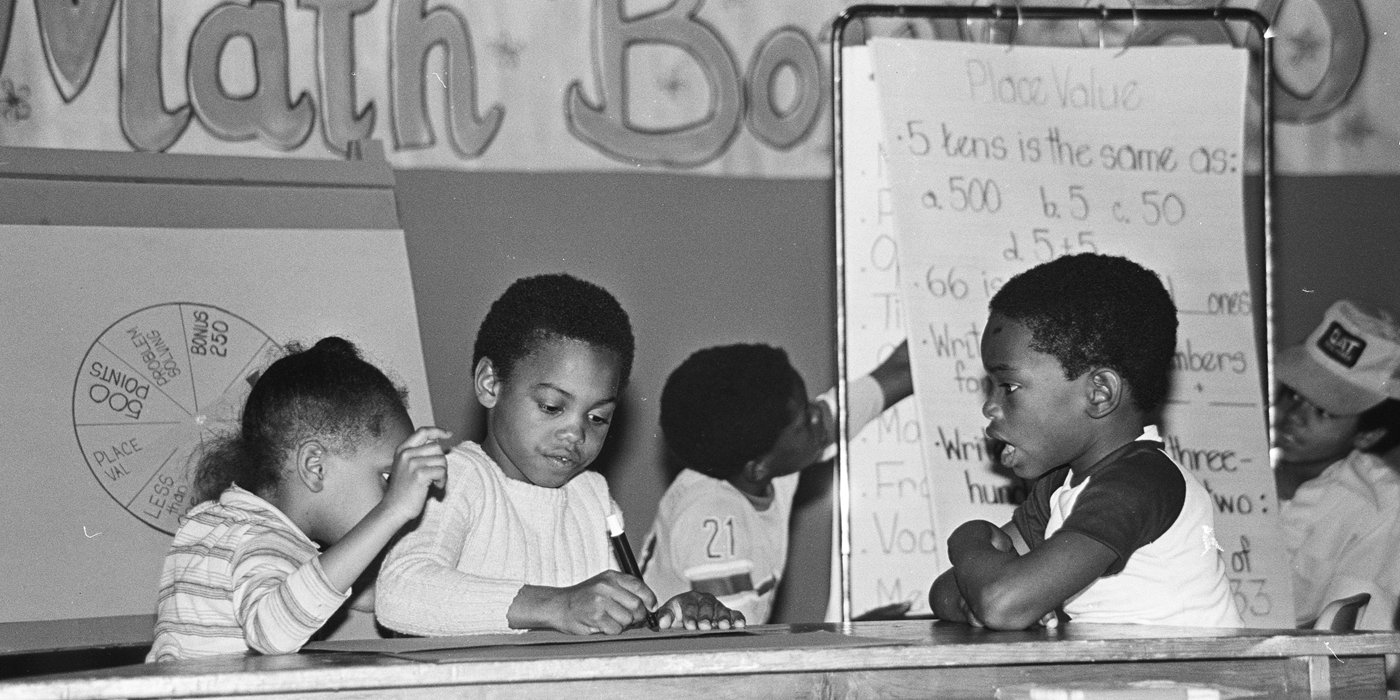

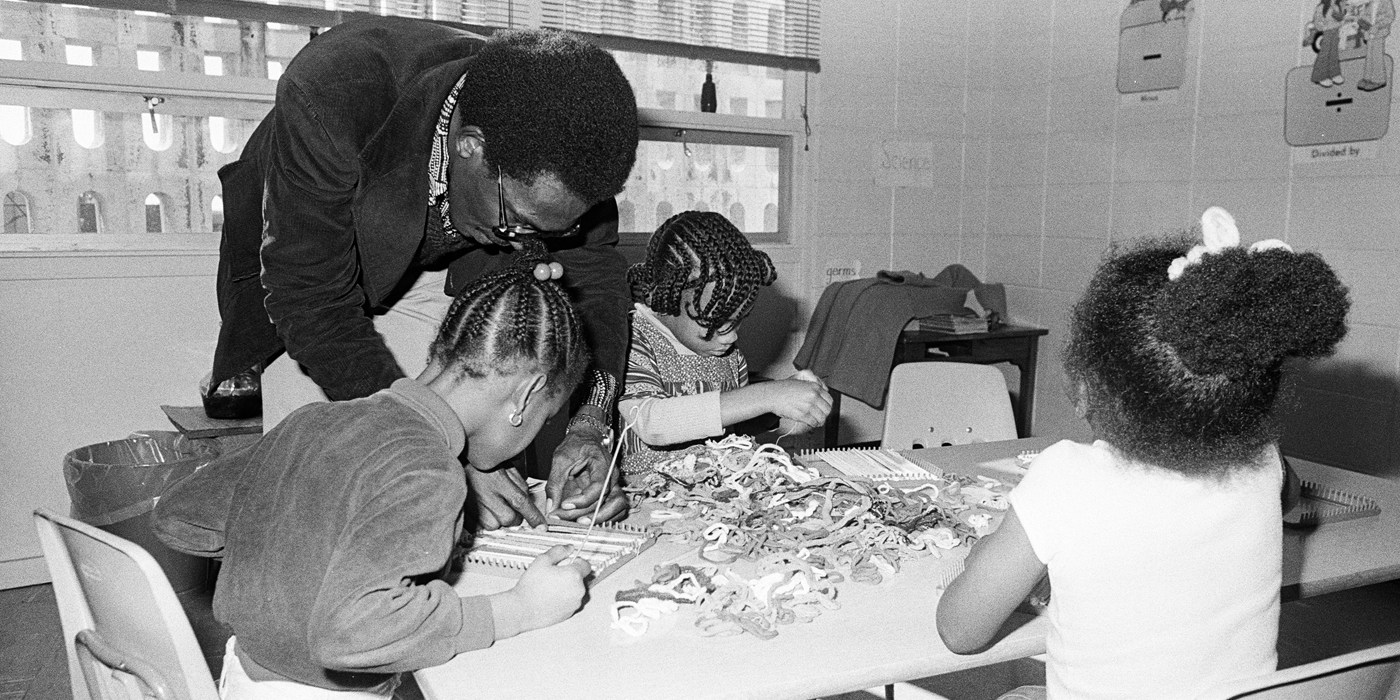

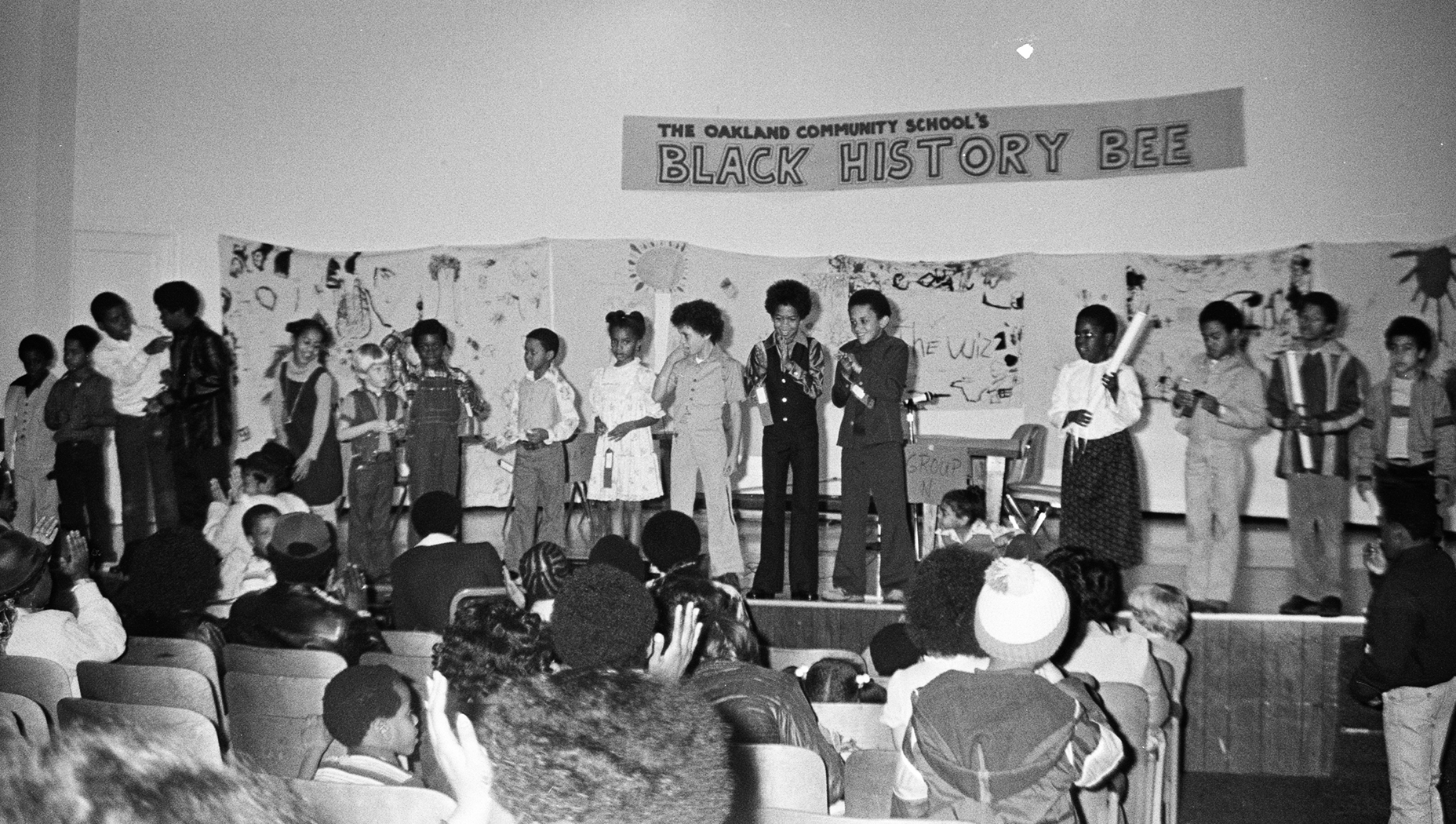

The school, situated in East Oakland, California, was open to the wider community and run by a nonprofit from 1973-1982. It provided academic and holistic support to black and low-income children, supplying three free meals a day (an extension of the Party’s Free Breakfast for School Children Program, which strongly influenced the U.S. to expand its School Breakfast Program), clothing, medical care and a curriculum rooted in black history. Its inception traces back to the fifth point of the Party's 10-Point Program and Platform, which demanded a quality education for students that teaches the genuine history of America and its peoples.

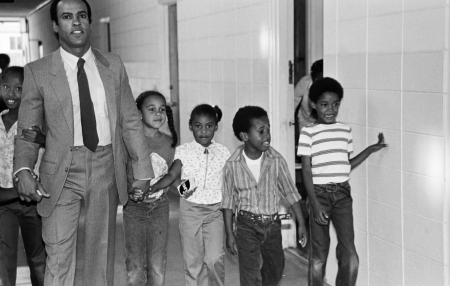

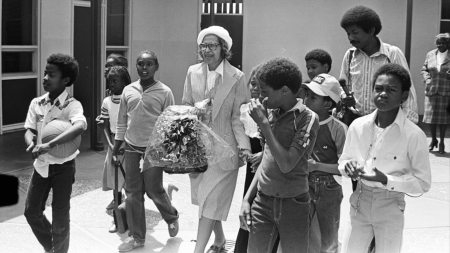

Oakland Community School challenged stereotypes about the so-called "uneducable youth.” It became a unique model for a community-based, child-centered and culturally inclusive elementary education, teaching children how, not what, to think. An elementary school by day and community center by night, it garnered widespread community support and recognition from notable visitors like Rosa Parks, Maya Angelou, James Baldwin, Willie Mays and Richard Pryor, among others.

UCI as a trusted partner

Huggins, a former Black Panther Party member whose life has been dedicated to public service, remains involved in the ongoing preservation of OCS. “UC Irvine fully engaged the concept of community-based schooling,” says Huggins, who stresses the need to document history beyond paper. “I'm grateful to everybody who stepped forward. Their understanding and their perspective has made all the difference.”

The collaboration between UCI and the Black Panther research cluster allows students to actively contribute to the preservation of community narratives. Students undertake diverse roles, from transcribing oral history interviews and video logging, to working on the OCS timeline and image database.

Project co-leader Desha Dauchan, associate professor of film and media studies, organized a screening and lecture series with L.A. Rebellion films and filmmakers which she later offered as a UCI course. She emphasizes the cluster's ability to offer students a window into a community and history. “The experience sparks a sense of agency and plants seeds for these students to consider that their histories and voices are valuable too,” Dauchan says.

As a curator for UCI Libraries Special Collections and Archives, Krystal Tribbett’s engagement with the cluster goes beyond scholarly pursuits. “This cluster constantly reminds me how important community-centered archival and documentary work is to share fuller histories of the past, to change narratives that have been misunderstood and to fill in the gaps with missing details,” she explains. The opportunity to learn from her co-leads and students is an added bonus for Tribbett.

Peer-to-peer mentorship

Central to the cluster is an unwavering commitment to mentorship and peer support, echoing the ethos encapsulated in the school’s mantra, "Each One Teach One." This guiding principle permeates the cluster's practices, fostering an environment where knowledge is shared, collaboration thrives and each voice is valued.

For Haleigh Marcello, a Ph.D. candidate in history, the cluster's philosophy became a catalyst for personal and academic growth. “I gained more appreciation for the value of collaborative work. So often, doing research is a solo endeavor. The research cluster is an example of what great work can be done when interdisciplinary scholars come together to preserve history and fight for social justice,” she says. After experiencing how powerful it was to bring history back to the community it originated from, she is in the process of founding an educational nonprofit based on her research in the cluster.

Witnessing cluster participants like Evelynn Cuautle ‘21 (B.A. public health policy, minor in Chicano/Latino studies) and Trinity Hunt-McGuinness ‘22 (B.A. gender and sexuality studies, minor in African American studies) evolve into historians and experts was a source of pride for Marcello, highlighting the transformation of the undergraduate fellows who embraced their new roles as historians. Cuautle found herself reflecting on her own educational experience as a low-income, first-generation student of color in the public school system.

As part of a diverse team of undergraduate students, Cuautle and Hunt-McGuinness lauded their mentors for providing essential support and encouragement – even emboldening Hunt-McGuinness to pursue graduate school. “Collaborating with scholars from different educational backgrounds made the experience engaging and well-rounded,” Cuautle says. “I felt seen.”

Tailoring educational opportunities

The cluster changed the course of Micherlange Francois-Hemsley’s ‘22 (B.A. African American studies, minor in criminology, law and society) academic and career goals, sparking an interest in preserving physical materials and increasing public accessibility.

“As a first-generation college graduate, these types of connections and relationships are invaluable to me as I embark on the beginning of my own career,” she shares. “Three years later, I haven’t experienced anything like this program in the type of skill building and mentoring opportunities.”

Her journey extends far beyond the cluster, which gave her opportunities to present at conferences, obtain other internships and act as the featured photographer for the Art, Power, and Community: A Black Panther Party’s 55th Anniversary Retrospective Multimedia Exhibit. Similarly to her peers, she notes that if not for these formative experiences, she wouldn’t have had the confidence to pursue a master’s degree, which she is currently completing.

After attending Francois-Hemsley’s exhibition, Johnny Vu ‘23 (B.A.s psychological science, criminology, law and society) was inspired to join the research cluster. The cluster's flexibility to tailor work to a fellow’s goals and interests – not unlike OCS itself – was appreciated by Vu, who, as a music history enthusiast, transcribed interviews between LeBlanc-Ernest and a former music teacher at OCS.

In his current role as an executive fellow at the California Student Aid Commission, he embodies the cluster's impact on career trajectory, as it inspired him to pursue a career in public service. “This cluster goes beyond a fellowship experience,” he explains. “Being able to listen to and speak with amazing activists and access the wealth of material is something unique. Interacting with the photos, videos and accounts from individuals from the school brought their stories to life.”

History reimagined

Ten years after the Black Panthers infamously marched to the state capitol in 1967 to rally for their right to bear arms, they returned – this time, however, with 10 children in tow to receive an award from the California State Department of Education as one of the most important models in elementary education. And while the Oakland Community School closed its doors to students in 1982, its legacy endures thanks to the efforts of UCI scholars.

What began as a documentary project by LeBlanc-Ernest has grown to become a historical treasure trove for future researchers. She and students are collaborating with filmmakers, writers and scholars to create various public humanities projects: an interactive digital “yearbook” that will preserve the narratives of former OCS students, teachers and parents; a traveling exhibit with never-before-seen images of OCS from a Black Panther Party photographer and UCI student-generated materials; and a documentary film series of the school.

“There are so many basic life lessons that come from the Oakland Community School experience. It wasn't a traditional school. It wasn't a charter school. It was a community school,” says LeBlanc-Ernest.

Applications for the 2024 Summer Internship Program open in mid-February.

Thank you to all of the donors who make these initiatives possible. You can support future BPOCSRC fellows by donating to its ZotFunder campaign.

Interested in reading more from the School of Humanities? Sign up for our monthly newsletter.

(Photos: Donald Cunningham Collection, Ericka Huggins Collection, Courtesy Angela D. LeBlanc-Ernest/The OCS Project)