by Jim Washburn

“Suffer well” may not be as inviting a salutation as “Live long and prosper,” but it was ideal for the title of a seminar series launched by the UCI Center for Medical Humanities in the fall of 2019. “The idea around ‘Suffer Well’ was to have speakers explore ways that suffering can become a portal to a more fulsome understanding of the human experience,” says center director James Kyung-Jin Lee. “To the extent that we can, we should alleviate suffering, but suffering can bring you a unique connectivity with other human beings. Albert Schweitzer, who himself suffered chronic illness even as he cared for other people, spoke of that as ‘a brotherhood of those who bear the mark of pain.’”

Unfortunately, the series was truncated because of the pandemic. But, Lee notes, the surfeit of suffering caused by COVID-19 has brought a sense of immediacy to other topics the Center for Medical Humanities covers in its curriculum and research: How does a doctor find a positive, honest way to talk with a terminally ill patient about death? What can be learned from the journals of patients who have trod that one-way path? Do the racism and sexism of earlier medical practices echo through the pandemic response today?

Such dark tones are only part of the palette that the medical humanities bring to the study of illness, wellbeing and the states in between. Programs in medical humanities are not uncommon, but they generally exist within medical schools and are limited in scope. UCI’s center, officially inaugurated in 2018 – after gestating as an initiative for a few years – bridges the School of Humanities, the Claire Trevor School of the Arts and the School of Medicine via a unique, interdisciplinary approach to health that encompasses research, curriculum development and community engagement. It has also offered undergraduate minor and graduate emphasis programs since 2016 and 2018, respectively.

“Insofar as medicine is interested in the care of human bodies,” Lee explains, “the humanities and the arts also ask questions about bodies and embodiment but ask them in different ways that can shed new light on what stories our bodies tell.”

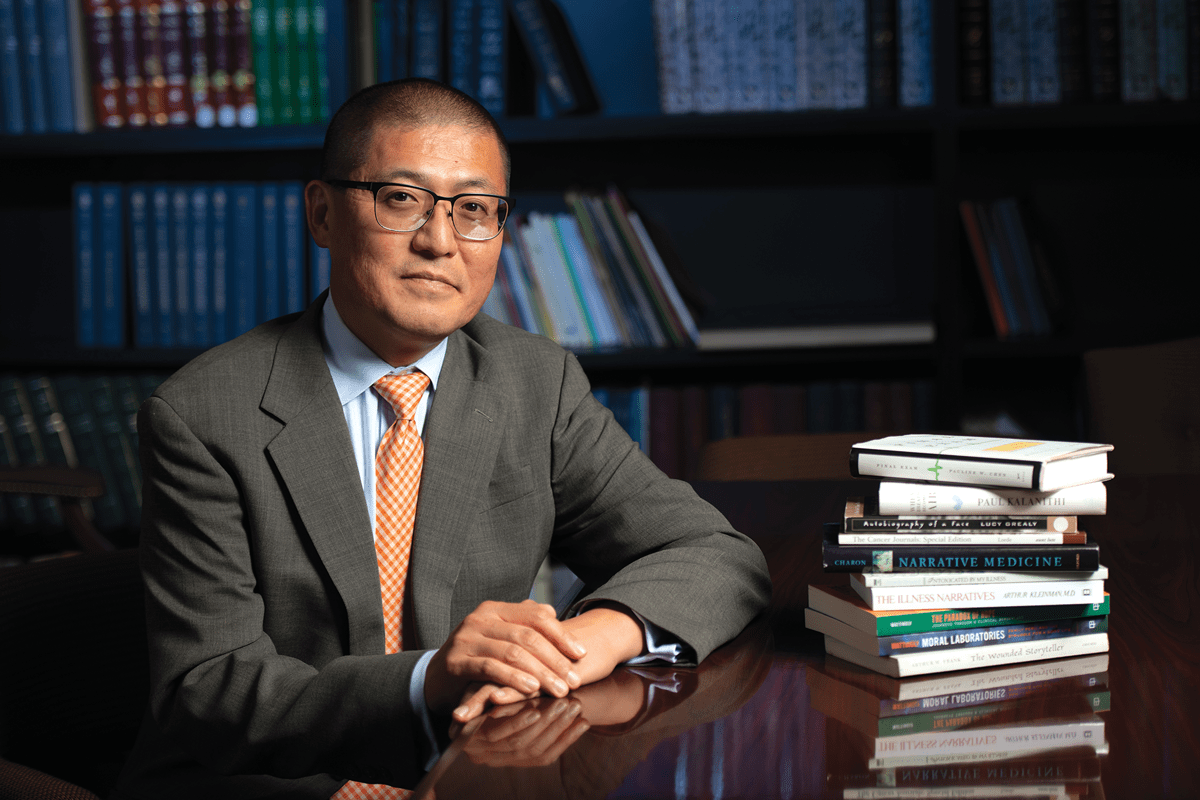

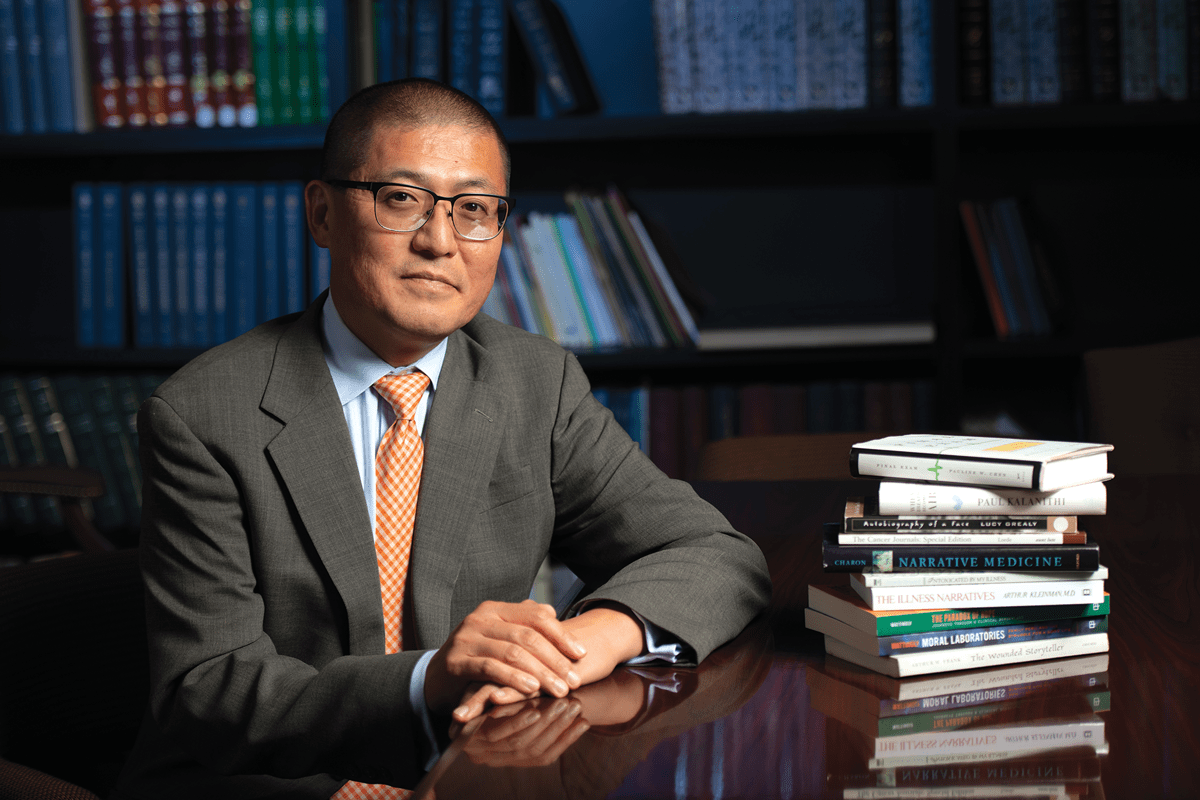

Lee is an associate professor in UCI’s Department of Asian American Studies. He’s also an Episcopal priest, which as much as anything spurred his passion for medical humanities. His pathway to priesthood included more than 400 hours of chaplaincy internship at a downtown Los Angeles hospital.

He recalls walking the halls of the oncology and surgery wards, talking with the patients, families and hospital workers. “I’m trained as a literary critic, but I was thoroughly ill-equipped to attend to the stories I witnessed there,” Lee says. “There was a whole other set of observational and analytical tools that I needed to develop in order to really be present for those very difficult stories that I had the privilege of hearing.”

Lee became director of UCI’s Center for Medical Humanities in 2019. He succeeded founding director and history professor Douglas Haynes, who along with family medicine professor Johanna Shapiro and the deans of the involved schools (Georges Van Den Abbeele and Tyrus Miller, humanities; Michael J. Stamos, medicine; and Stephen Barker, arts) were the prime movers in bringing the center into being.

While Haynes is now UCI’s vice chancellor for equity, diversity & inclusion, his continuing work as a historian has included tracing the evolution and codification of the medical profession in the British Empire and the U.S.

He says the center’s inception was a confluence of many things. Development of the proposal for it started around the time the Affordable Care Act was implemented, which elevated attention to healthcare in general and prompted people with research interests in health, healing and well-being to begin asking new questions.

“We didn’t know how large a community was forming here – or how intersecting their interests were – until we started having brainstorming sessions about the center,” Haynes says. “It’s consequential when you get faculty – who are very habituated to their own schools and professional disciplines – to feel sufficiently open to the value of interdisciplinarity that they’re willing to step into this uncomfortable space that had never been done before.”

The conditions for the center were there, he adds, but it made all the difference when Chancellor Howard Gillman, who was UCI provost at the time, launched an interschool excellence initiative. “He created a very significant incentive to explore the possibilities, and that’s what moved us forward,” Haynes says.

The campus event announcing the center in 2018 included dramatic reenactments of scenes from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Since then, courses and research have varied widely, from how issues of health and medicine have been depicted on the theatrical stage from ancient Greece to the present day to how the nuclear age shaped impressions of health and medical care.

Sometimes the courses hold up an unflattering mirror to the history of medicine, in which the practices leading to medical developments were often no more advanced than the prejudices of their times. For example, Lee says, “the foundations of obstetrics and gynecology in the 19th century emerged principally through the work of physician James Marion Sims, who performed experiments on enslaved women, obviously with no notion of consent. You have to wonder if history like that, Tuskegee and other events factors into the generalized skepticism toward vaccinations in Black communities today.”

History professor Adria Imada, who teaches both undergraduate and graduate medical humanities courses, sometimes draws from her book An Archive of Skin, An Archive of Kin: Disability and Life-Making During Medical Incarceration, about the forced sequestration of persons with Hansen’s disease (leprosy) in Hawaii.

She also uses media and film in her classes, some taken from the arts, such as paintings, and others that might be framed as art, such as news footage from 1990 of people leaving their wheelchairs to crawl up the steps of the U.S. Capitol to demonstrate their lack of access. “That may not have been on a theatrical stage,” Imada says, “but it was definitely a political stage, and it had profound outcomes in the fight for disability rights.”

“It’s important to think expansively and beyond disciplinary boundaries about medicine and disability,” she continues, “so that health isn’t simply the purview of clinical medicine but that everyone has an investment in understanding how health is experienced in the present, how it was experienced in the past and how to change potential outcomes for the future.”

Many of the medical humanities students are looking toward careers in medicine. Dean Wong ’19 pursued the medical humanities minor while majoring in psychology & social behavior. He says the course descriptions in the medical humanities syllabus were what made him choose UCI over other universities.

Wong now works at the UCI School of Medicine as a medical student coordinator, is one of the organizers of a Flying Samaritans medical clinic in Mexico and hopes to eventually earn a medical degree. He says his classes in medical humanities prepared him more than he had imagined.

Says Wong: “Some of the memoirs that we read were very raw and made me realize that this is life for many people – their struggles as patients dealing with the inequities of the healthcare system. It really made me want to become a voice for those people.”

Originally published in UCI Magazine, Winter 2021

Images: Adria Imada teaches a Medical Humanities 1 course; UCI Center for Medical Humanities director James Kyung-Jin Lee; and Founding director and history professor Douglas Haynes. Photo credits: Steve Zylius / UCI

Related links:

“Suffer well” may not be as inviting a salutation as “Live long and prosper,” but it was ideal for the title of a seminar series launched by the UCI Center for Medical Humanities in the fall of 2019. “The idea around ‘Suffer Well’ was to have speakers explore ways that suffering can become a portal to a more fulsome understanding of the human experience,” says center director James Kyung-Jin Lee. “To the extent that we can, we should alleviate suffering, but suffering can bring you a unique connectivity with other human beings. Albert Schweitzer, who himself suffered chronic illness even as he cared for other people, spoke of that as ‘a brotherhood of those who bear the mark of pain.’”

Unfortunately, the series was truncated because of the pandemic. But, Lee notes, the surfeit of suffering caused by COVID-19 has brought a sense of immediacy to other topics the Center for Medical Humanities covers in its curriculum and research: How does a doctor find a positive, honest way to talk with a terminally ill patient about death? What can be learned from the journals of patients who have trod that one-way path? Do the racism and sexism of earlier medical practices echo through the pandemic response today?

Such dark tones are only part of the palette that the medical humanities bring to the study of illness, wellbeing and the states in between. Programs in medical humanities are not uncommon, but they generally exist within medical schools and are limited in scope. UCI’s center, officially inaugurated in 2018 – after gestating as an initiative for a few years – bridges the School of Humanities, the Claire Trevor School of the Arts and the School of Medicine via a unique, interdisciplinary approach to health that encompasses research, curriculum development and community engagement. It has also offered undergraduate minor and graduate emphasis programs since 2016 and 2018, respectively.

“Insofar as medicine is interested in the care of human bodies,” Lee explains, “the humanities and the arts also ask questions about bodies and embodiment but ask them in different ways that can shed new light on what stories our bodies tell.”

Lee is an associate professor in UCI’s Department of Asian American Studies. He’s also an Episcopal priest, which as much as anything spurred his passion for medical humanities. His pathway to priesthood included more than 400 hours of chaplaincy internship at a downtown Los Angeles hospital.

He recalls walking the halls of the oncology and surgery wards, talking with the patients, families and hospital workers. “I’m trained as a literary critic, but I was thoroughly ill-equipped to attend to the stories I witnessed there,” Lee says. “There was a whole other set of observational and analytical tools that I needed to develop in order to really be present for those very difficult stories that I had the privilege of hearing.”

Lee became director of UCI’s Center for Medical Humanities in 2019. He succeeded founding director and history professor Douglas Haynes, who along with family medicine professor Johanna Shapiro and the deans of the involved schools (Georges Van Den Abbeele and Tyrus Miller, humanities; Michael J. Stamos, medicine; and Stephen Barker, arts) were the prime movers in bringing the center into being.

While Haynes is now UCI’s vice chancellor for equity, diversity & inclusion, his continuing work as a historian has included tracing the evolution and codification of the medical profession in the British Empire and the U.S.

He says the center’s inception was a confluence of many things. Development of the proposal for it started around the time the Affordable Care Act was implemented, which elevated attention to healthcare in general and prompted people with research interests in health, healing and well-being to begin asking new questions.

“We didn’t know how large a community was forming here – or how intersecting their interests were – until we started having brainstorming sessions about the center,” Haynes says. “It’s consequential when you get faculty – who are very habituated to their own schools and professional disciplines – to feel sufficiently open to the value of interdisciplinarity that they’re willing to step into this uncomfortable space that had never been done before.”

The conditions for the center were there, he adds, but it made all the difference when Chancellor Howard Gillman, who was UCI provost at the time, launched an interschool excellence initiative. “He created a very significant incentive to explore the possibilities, and that’s what moved us forward,” Haynes says.

The campus event announcing the center in 2018 included dramatic reenactments of scenes from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Since then, courses and research have varied widely, from how issues of health and medicine have been depicted on the theatrical stage from ancient Greece to the present day to how the nuclear age shaped impressions of health and medical care.

Sometimes the courses hold up an unflattering mirror to the history of medicine, in which the practices leading to medical developments were often no more advanced than the prejudices of their times. For example, Lee says, “the foundations of obstetrics and gynecology in the 19th century emerged principally through the work of physician James Marion Sims, who performed experiments on enslaved women, obviously with no notion of consent. You have to wonder if history like that, Tuskegee and other events factors into the generalized skepticism toward vaccinations in Black communities today.”

History professor Adria Imada, who teaches both undergraduate and graduate medical humanities courses, sometimes draws from her book An Archive of Skin, An Archive of Kin: Disability and Life-Making During Medical Incarceration, about the forced sequestration of persons with Hansen’s disease (leprosy) in Hawaii.

She also uses media and film in her classes, some taken from the arts, such as paintings, and others that might be framed as art, such as news footage from 1990 of people leaving their wheelchairs to crawl up the steps of the U.S. Capitol to demonstrate their lack of access. “That may not have been on a theatrical stage,” Imada says, “but it was definitely a political stage, and it had profound outcomes in the fight for disability rights.”

“Insofar as medicine is interested in the care of human bodies, the humanities and the arts also ask questions about bodies and embodiment but ask them in different ways that can shed new light on what stories our bodies tell.”

“It’s important to think expansively and beyond disciplinary boundaries about medicine and disability,” she continues, “so that health isn’t simply the purview of clinical medicine but that everyone has an investment in understanding how health is experienced in the present, how it was experienced in the past and how to change potential outcomes for the future.”

Many of the medical humanities students are looking toward careers in medicine. Dean Wong ’19 pursued the medical humanities minor while majoring in psychology & social behavior. He says the course descriptions in the medical humanities syllabus were what made him choose UCI over other universities.

Wong now works at the UCI School of Medicine as a medical student coordinator, is one of the organizers of a Flying Samaritans medical clinic in Mexico and hopes to eventually earn a medical degree. He says his classes in medical humanities prepared him more than he had imagined.

Says Wong: “Some of the memoirs that we read were very raw and made me realize that this is life for many people – their struggles as patients dealing with the inequities of the healthcare system. It really made me want to become a voice for those people.”

Originally published in UCI Magazine, Winter 2021

Images: Adria Imada teaches a Medical Humanities 1 course; UCI Center for Medical Humanities director James Kyung-Jin Lee; and Founding director and history professor Douglas Haynes. Photo credits: Steve Zylius / UCI

Related links:

Medical Humanities

Asian American Studies

History