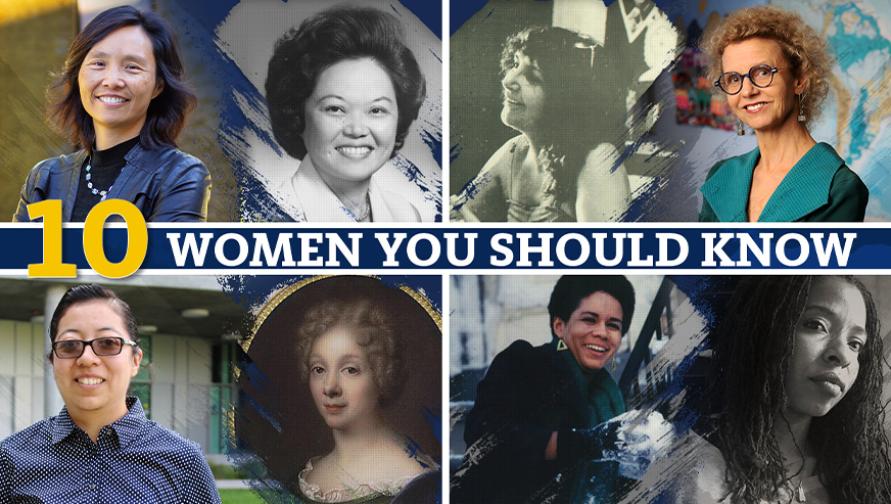

This Women’s History Month, UCI School of Humanities scholars honor the women whose efforts transformed their communities – from making history in the U.S. government and fighting against political oppression, to writing the texts, curating the art and directing the films that defined generations.

UCI Humanities professors in a wide range of fields – Asian American studies, classics, film and media studies and more – write literature and teach courses on the women who shaped history. Here, they shine light on ten such women in their own words.

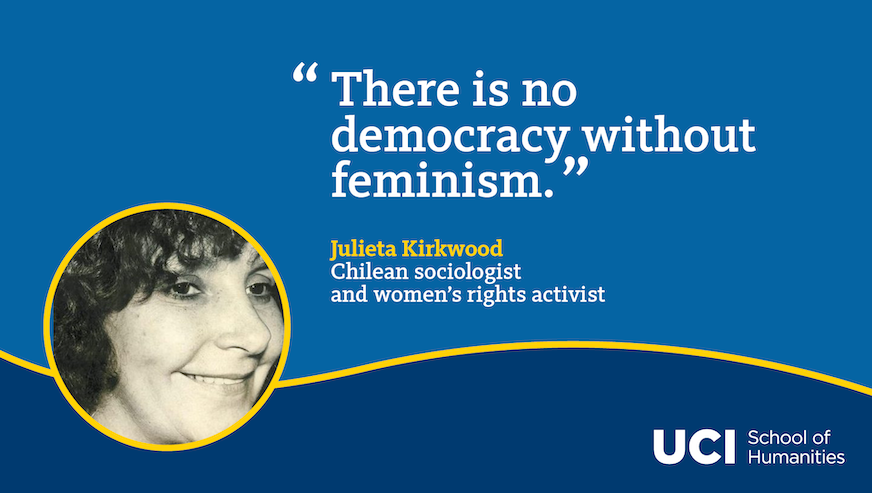

1. Julieta Kirkwood (1936-1985) was a Chilean sociologist and women’s rights activist whose work was foundational to the second-wave feminist movements in Latin America that helped end military dictatorships in Chile, Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. Her 1982 book, Ser Política en Chile: Las Feministas y Los Partidos Políticos (Being a Political Woman in Chile: Feminists and the Political Parties), argued that patriarchy was the basis of authoritarianism but that getting rid of military rule would not, by itself, create a true democracy that included women on equal terms. Kirkwood insisted that only independent feminist movements could transform Chile’s left wing political parties and other male-dominated institutions that sought democratic transformation. Moreover, Kirkwood asserted the importance of studying “women’s history” to creating an inclusive society. She co-founded the first women’s studies programs in Chile, which were directly linked to grassroots activism. Throughout the 1980s, feminist organizations in Chile and elsewhere in Latin America built on Kirkwood’s insights and created vibrant social movements that simultaneously challenged authoritarianism and patriarchy with the slogan: “Democracy in the country and in the home!”

- Selected by Heidi Tinsman, professor of history and gender and sexuality studies and the author of Buying into the Regime: Consumption and Grapes in Cold War Chile and the United States (Duke, 2014) and Partners in Conflict: The Politics of Gender, Sexuality, and Labor in the Chilean Agrarian Reform, 1950-1973 (Duke, 2002).

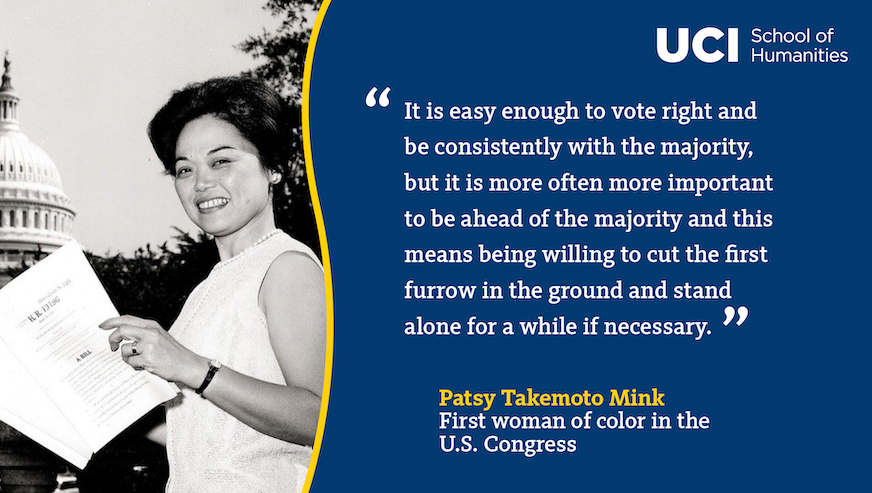

2. Patsy Takemoto Mink (1927-2002), a third-generation Japanese American from Hawai‘i, became the first woman of color in the U.S. Congress and eventually served for 24 years in the House of Representatives. She ran for the U.S. Presidency in 1972 as an anti-war candidate. Title IX, which mandates gender equity in all aspects of educational institutions that receive federal funding, was renamed after Mink when she passed away in 2002. What motivated Mink in her groundbreaking political career? A 2008 documentary film about her life uses the phrase “ahead of the majority” in its title. Mink uttered these words in 1975 to explain her political vision:

“It is easy enough to vote right and be consistently with the majority, but it is more often more important to be ahead of the majority and this means being willing to cut the first furrow in the ground and stand alone for a while if necessary.”

Mink was willing to take political risks to advocate for racial and gender justice, environmental protection, and the rights and protection of workers and the impoverished. She did not always have to do this alone, though, since she collaborated with movement advocates to introduce and lobby for innovative legislation in the U.S. House of Representatives. Mink did not always “win,” but she consistently fought.

- Selected by Judy Tzu Chu Wu, professor of Asian American studies and director of the UCI Humanities Center. Wu is the author of Dr. Mom Chung of the Fair-Haired Bastards: the Life of a Wartime Celebrity (University of California Press, 2005) and Radicals on the Road: Internationalism, Orientalism, and Feminism during the Vietnam Era (Cornell University Press, 2013). Fierce and Fearless (NYU Press, 2022), her forthcoming biography on Mink, co-written with Mink’s daughter Gwendolyn, comes out this May.

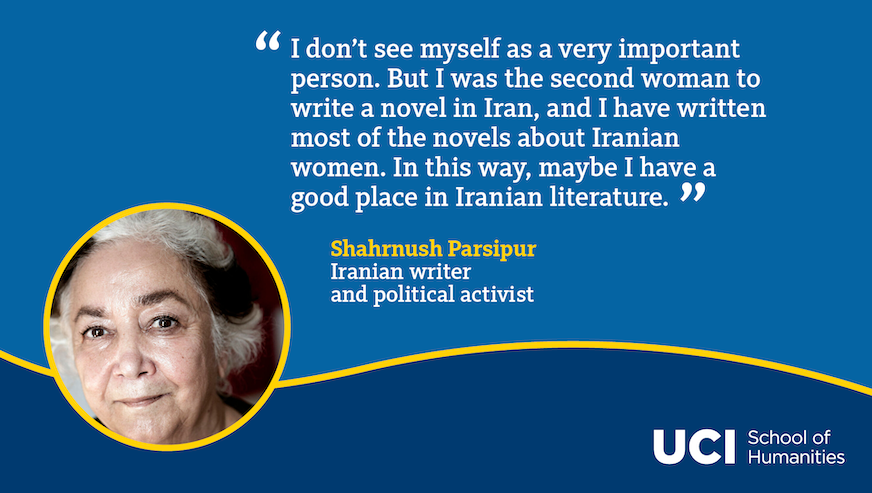

3. Shahrnush Parsipur, an Iranian writer who was imprisoned both before and after the Iranian revolution of 1979 for her stance against political oppression, has been living in northern California since the 1990s. She was born in Tehran in 1946 and, after attending the University of Tehran, she worked at the National Iranian Television. When a well-known poet and activist, Khosro Golsorkhi, was executed, she resigned her post in protest. In the wake of the 1979 revolution, Parsipur was arrested and held in prison without charge for over four years. She was arrested again in 1989 after the publication of her novella, Women without Men, which has been translated twice into English and was made into a feature film by the Iranian American photographer and filmmaker, Shirin Neshat. Parsipur is also known for her short stories, novels and prison memoirs. During one of her visits to UCI, I asked her about her grueling prison experiences particularly after the revolution, and her answer spoke volumes about her abiding commitment to political justice: “Going to prison was a relief to me. Before my arrest, I felt helpless, hearing news of mass arrests and executions. In prison, at least I knew I couldn’t do anything else.”

-

Selected by Nasrin Rahimieh, professor of comparative literature and the author of Iranian Culture: Representation and Identity (Routledge, 2017) and Missing Persians: Discovering Voices in Iranian Cultural Heritage (Syracuse University Press, 2001).

4. Ida B. Wells (1862-1931) was a journalist, political commentator and anti-lynching activist. Her early work was based in Memphis, Tennessee, but she later moved to Chicago to escape the ceaseless threats she received for her pioneering work against the Jim Crow South’s regimes of violence. While she earned renown for her investigative journalism, her exposition of early criminological discourse is relatively underexplored. Her works Southern Horrors (1892) and The Red Record (1895) not only document extrajudicial killings of Black southerners but also offer rich insights on how the categories of the “criminal” and “criminality” are enmeshed in racial and class biases. Her work examines the violence inherent in lynching photography where it does not merely represent violence but also acts as a catalyst for it. She thus paved the way for modern scholarship on visual technologies and their vexed relationship with racialized violence.

-

Selected by Sri Basu, an assistant professor of English. Her research focuses on 18th and 19th century American Literature and the growing field of Black Atlantic Studies. Her current book project, “Punishment and Revolution,” analyzes Anglophone Black Atlantic literature and offers a new account of how extra-economic violence racialized New World labor.

5. Born as Selma Deitch in Brooklyn in 1930, Selma James is a singularly prolific thinker, writer, editor and activist. Her wide-ranging essays have been collected in two volumes, Sex, Race, and Class – The Perspective of Winning: A Selection of Writings, 1952–2011 (2012) and Our Time Is Now: Sex, Race, Class, and Caring for People and Planet (2021). In the 1940s, she was a member of the Johnson-Forest Tendency along with the Marxist thinkers C.L.R. James, Raya Dunayevskaya and Grace Lee Boggs. Her 1952 pamphlet, “A Woman’s Place,” is an early, clear-eyed examination of the tedious, unending, unpaid and alienating work of housekeeping and childcare. Pointing out that this was “an inhuman setup,” James also described how women created meaningful relationships of camaraderie, mutual support and collective organizing with each other. In 1972, James co-authored with Mariarosa Dalla Costa the influential manifesto, The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community. By 1972, with greater numbers of women in the paid workforce, it was clear that going to work outside the home did not free women from housework but rather created even more work for women. Calling on women to “refuse the myth of liberation through work,” James and Dalla Costa proposed demanding to be paid for housework as another strategy to achieve broad recognition of women’s social and economic importance and to spur women to "completely discover their own possibilities.” In March 1972, James and Dalla Costa started the international campaign known as “Wages for Housework,” which marks its 50th anniversary this month. In March 2000, James helped to launch the ongoing Global Women’s Strike with the call to “Invest in caring, not killing.”

-

Selected by Laura Kang, professor of gender and sexuality studies and author of Traffic in Asian Women (Duke University Press, 2020), Compositional Subjects: Enfiguring Asian/American Women (Duke University Press, 2002) and writing away here: a korean/american anthology (Oakland, CA: Korean American Arts Festival Committee, 1994).

6. American art collectors and museum founders Isabella Stewart Gardner and Peggy Guggenheim counted among their role models the Italian Renaissance princess, Isabella d’Este (1474-1539), marchioness of Mantua, whose acclaimed collection once filled a suite of rooms in what is now Mantua’s Ducal Palace Museum. Unlike other women, who typically kept modest galleries of family portraits and religious images, d’Este borrowed a cultural practice from contemporary male princes and designed a complex display space called the studiolo (study). She was passionate and tireless in commissioning artworks and decorations for this project. Gilding, intarsia panels, frescoes, tiles and enigmatic emblems adorned the ceilings, walls and floors, while paintings, books, cameos, bronzes, Roman antiquities and musical instruments played starring roles in the studiolo’s performance of her culture. A signature instance of personal “branding,” the studiolo was unparalleled as an architectural and artistic expression of explicitly feminine Renaissance sophistication. This collection is dispersed in museums around the world today; but still gathered in Mantua’s State Archive is d’Este’s correspondence: 28,000 letters that document the life and times of a female co-ruler and cultural visionary in Renaissance Italy, revealing tales of art and politics, diplomacy, music, travel, fashion, family and more.

-

Selected by Deanna Shemek, professor of Italian and European studies. Shemek authored In Continuous Expectation: Isabella d’Este’s Reign of Letters (Centre for Renaissance and Reformation Studies, 2021) and translated and edited Isabella d’Este: Selected Letters (Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2017).

7. Pak Kyong-ni (1926-2008) was a prominent South Korean writer, best-known for crafting the longest historical novel, The Land, which critics rate as the most important piece of modern Korean writing. The novel covers the story of female protagonist Ch’oe Sŏ-hŭi as she lives through the turbulence of Korea’s modernization from the late 19th century to Japanese colonization (1910-1945), defending and restoring her family estate while emigrating to Manchuria then returning to Korea. She wrote the 16-volume story over a 25-year period, between 1969-1994, completing it on August 15, the day of Korean independence. The Land has been made into a TV series, a movie and an opera; translated into several languages including English, French, German and Japanese; and it is included in UNESCO's Collection of Representative Works. Celebrating Pak Kyong-ni’s literary career in 2011, an international literary prize was established in her name: the Pak Kyong-ni International Literary Prize. Its internationally renowned recipients include UCI Distinguished Professor Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o (2016).

-

Selected by Chungmoo Choi, professor of East Asian studies and the author of Healing Historical Trauma in South Korean Film and Literature (Routledge, 2020) and editor of Voices of the Korean Comfort Women: History Rewritten from Memories (Routledge, forthcoming in 2022).

![A quote from Anne Dacier: "If we tolerate false [artistic] principles spoiling the mind and judgment [of young people], there are no more resources left for them. Bad taste and ignorance will finish off this work of leveling. As a result, literature will be entirely lost. And it is literature which is the source of good taste, of politeness, and of all good government."](/sites/default/files/2022-03/anne.png)

8. Anne Le Fèvre Dacier (1645-1720) was a classical scholar who translated several ancient works throughout her lifetime. Exceedingly proficient in Greek and Latin, she was able to publish her first translation of the poetry of Callimachus in her mid-twenties. This translation brought her renown among other French classicists and led to her being appointed assistant tutor to the Dauphin (heir apparent to the throne) of France. Despite her prominence, Dacier encountered resistance to her work when she translated the Iliad in 1699. Unlike her male colleagues who took liberties with the epic because they thought the original Greek lacked sophistication and needed to reflect the more modern sensibilities of French society, she believed her unadorned translation highlighted the inherent superiority of ancient authors. She would continue to champion the ancients in several treatises, and her translations continued to influence the work of other classicists. In fact, Emily Wilson, who in 2017 became the first woman to publish a translation of the Odyssey into English, cited Dacier as someone whom she looked at with “respect and admiration.”

-

Selected by Aleah Hernandez, an assistant professor of classics. Hernandez’s research focuses on issues of violence and gender in classical literature. She is currently developing several projects that highlight the intersection of classics and popular culture.

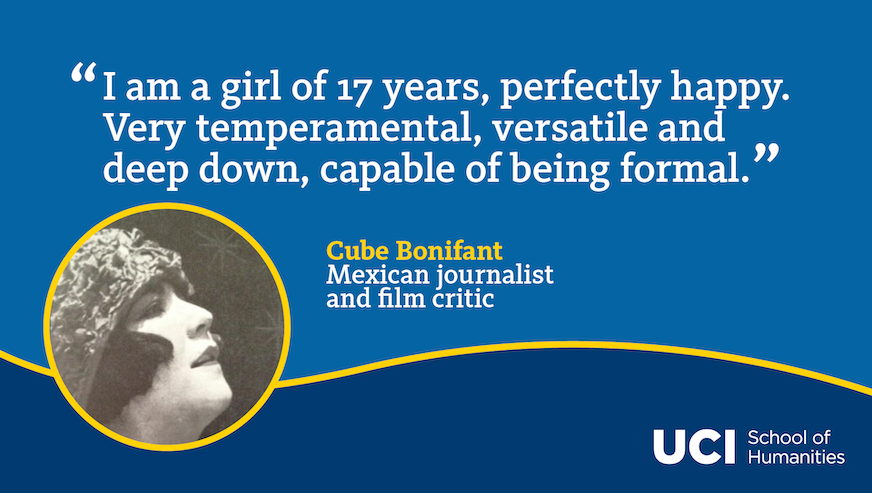

9. Cube Bonifant (1904-1993) was a Mexican journalist and film critic. She began publishing a regular column in 1921 in El Universal Ilustrado, one of the country’s most important cultural magazines. She was 17 and did not look back. Her outspoken, funny and irreverent articles were a quick success, though they did earn her a number of critics from the older – and male – intellectual establishment. The Mexican Revolution had just ended, and the country was eager to leave the war behind – even though violence and rampant inequality was far from over. Bonifant became an emblem of the new, modern woman who smoked in public, wore her hair in a short flapper style, hollered at bullfights and often got away with writing about what she wanted. Starting in the late 1920’s, Bonifant began publishing a column on film, and she soon became one of the most important and prolific film critics in Mexico, writing well into the late 1940’s.

-

Selected by Viviane Mahieux, associate professor of Spanish and author of Urban Chroniclers in Modern Latin America: The Shared Intimacy of Everyday Life (University of Texas Press, 2011) and Una pequeña marquesa de Sade: Crónicas selectas 1921-1948 (Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, 2009).

10. Kathleen Collins (1942-1988) was raised in Jersey City and educated at Skidmore and The Sorbonne. She was an activist with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee during the civil rights movement who went on to carve out a career for herself as a playwright and filmmaker during a time when Black women were rarely seen in those roles. Collin’s films explored themes of marital malaise, male dominance, freedom of expression and intellectual pursuit. Her characters are often self-reflective women finding their power. Her most popular work is the feature film “Losing Ground,” followed by two plays, “In the Midnight Hour” and “The Brothers. “A never-before-released collection of short fiction, Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?, was published by Ecco Press in 2016. A bold cinematic voice, Collin’s films in the 1980s paved the way for her mentee Julie Dash’s later film “Daughters of The Dust” in 1992, the first film directed by an African American woman to receive wide distribution in the United States. Collins was married twice and had two children before her death at age 46, from breast cancer.

-

Selected by Desha Dauchan, associate professor of teaching in film and media studies. Her research focuses on media and activism, African American film and African diaspora cinema. She wrote, produced, directed and edited the short film “Covered.”