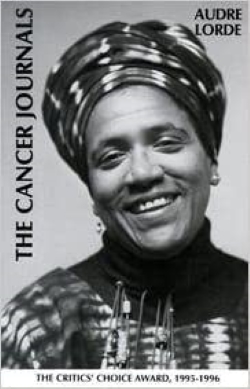

There were breast cancer memoirs prior to Lorde’s, but hers has staying power because she was unapologetically, searingly honest about the ways she suffered both from her cancer and from her treatment. She explained how the care she received from some doctors and nurses was sub-par because she was a Black lesbian. This book is a classic because Lorde put everything on the table and didn’t flinch.

By Megan Cole

The famed American writer Susan Sontag once wrote, “Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick. Sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.” In other words, to encounter illness and injury – and thus to require treatment and care – is to be human.

For James Kyung-Jin Lee – associate professor of Asian American studies and director of UCI’s Center for Medical Humanities – it’s time to explore “that other place” that makes us human. Now more than ever, Lee believes that we need the medical humanities to create more empathetic “citizens” and caretakers, and to transform the way we think about medicine and public health altogether.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the social and medical realms have become ever more intertwined, but the relationship between the humanities and healthcare wasn’t always so clear. When Lee earned his English Ph.D. in 2000, the field of medical humanities – which examines the intersections of culture and medicine – was just emerging. It wasn’t until 2009 that Lee, already a tenured professor of Asian American literature, interned as a hospital chaplain in Downtown Los Angeles and began to “read and interpret the world” through a medical humanist lens.

“It was during my encounters with patients, families and hospital staff that I became aware of the abundance of stories within the walls of the hospital,” Lee says. “The stories being shared with me – stories of illness, death, dying and suffering – made that space a crucible of human experience. At times, it was impossibly hard to listen, but it was also transformative.”

After coming to know patients as “humans with complex narratives, histories and identities” rather than as impersonal numbers on a medical chart, Lee learned about the burgeoning field of medical humanities. As a literary scholar, he was drawn to the long canon of memoirs and novels about people’s experiences of illness, the social impacts of medicine, and various philosophies of wellness.

However, Lee was immediately struck by the disproportionate whiteness of the existing canon. “A decade ago,” he recalls, “if you Googled ‘illness memoir,’ there was almost no diversity in the results.” Given his area of expertise, Asian American literature, Lee wondered: Why were there so few Asian American illness narratives? Why, even when so many medical professionals are Asian American, were there so few stories about Asian American medical professionals getting sick?

These questions eventually led to his new book, Pedagogies of Woundedness: Illness, Memoir, and the Ends of the Model Minority (Temple University Press, 2022), which interrogates the “model minority” myth as it applies to Asian American medical practitioners. Doctors – especially Asian American doctors – are supposed to be invincible, Lee explains, so nobody expects them to get ill and die. These “exceptional” physicians are envisioned as providers of care, never recipients. When the public is faced with the fact that even these supposed paragons of health are medically vulnerable, they begin to panic.

“People think, If this Asian American, ‘model minority’ physician can get sick and die – well, then, anyone can die! Then I can die! How am I supposed to deal with that? Then, they think, I wonder if this Asian American who wasn't supposed to die, but did die, can teach me how to die well,” Lee says. “Just as Americans have looked in the last two decades to Asian American physicians as spokespersons for American medicine writ large, so do Asian Americans now become ‘pedagogues’ teaching American readers how to get sick and die.”

Lee mentions that in the past decade, more Asian American physicians – Paul Kalanithi, Siddhartha Mukherjee and Atul Gawande among them – have broken this silence and have begun diversifying the canon of “illness memoirs” by writing their own narratives about illness, disability, medical vulnerability and mortality. In Pedagogies of Woundedness, Lee explains that this hasn’t always been the case.

“Until recently, publishers didn’t know what to do with an Asian American illness story. People of color would get called out for talking about race and identity in what publishers wanted to be a straight-up illness story,” Lee says. “There were readerly expectations that the illness story is normatively white. People didn’t want to read about how race impacted an illness story.”

Now, as director of UCI’s Center for Medical Humanities, Lee and his colleagues work to change that, and to ensure that the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, disability and medicine are considered in conversations about changing the current paradigms of healthcare.

“In the medical humanities, we want to help medical professionals – and the public – to acknowledge that there are other ways of understanding illness and health beyond the strictly biomedical,” Lee says. “We want to bring in other voices and other perspectives in the clinical setting in order to help make medicine more equitable and sensitive to patients’ needs and desires.”

During the pandemic, the Center for Medical Humanities – which hosted several workshops on mental health in the COVID-19 era, as well as organized a seminar series about societal suffering and wellness – has been more needed than ever.

“Over the past couple of years, the Center for Medical Humanities has spent a lot of time thinking about not only the immediate, obvious effects of the pandemic, but also how the pandemic has brought to light long-standing structural inequalities and systemic brokenness within healthcare and society,” Lee says. “We’re thinking together in a scholarly, intellectual community, as well as a community of care. We’re asking how we can build models of care, community and interdependency, and how we might move away from the expectation of normative, autonomous, independent and productive bodies. The pandemic has proven that those expectations are an impossibility.”

The medical community will certainly face more challenges as the pandemic continues to unfold, adds Lee, but building more equitable and empathetic societies, and highlighting the “care, community and interdependency” we all rely on, is just the sort of healing medical humanists are capable of.

Medical Humanities book recommendations

by James Kyung-Jin Lee

The Cancer Journals by Audre Lorde (1980)

Intoxicated by My Illness by Anatole Broyard (1993)

In 1990, this former editor of the New York Times Book Review was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He used these essays to reflect on the doctor-patient relationship and developed what he called a “style of illness".

Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy (1994)

This very important book—in which Grealy describes her life before and after her diagnosis with Ewing’s sarcoma—is simultaneously an illness narrative and a disability narrative.

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi (2016)

If you know any story about illness, it’s probably this one. Kalanithi’s lung cancer memoir was on bestseller lists for months. It resonated because, as both an Asian American and a neurosurgeon, Kalanithi wasn’t supposed to get sick and die so early. When we think of physicians, there’s an automatic expectation that of course they should be healthy. It’s almost oxymoronic to think of being treated by a sick doctor. But there are plenty of healthcare professionals with illnesses and disabilities. Kalanithi expertly explores that terrain in his memoir—an instant classic.