Removing Religion from Dia de Los Muertos?

by Aldo Alcala, Fall '24 RS Intern

El Dia de Muertos, or Day of the Dead, is arguably the most famous holiday to come out of Mexico. Taking place during the Christian period of Allhallowtide, a triduum of holidays that includes Halloween, All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day, it is a time of reverence and remembrance of one’s deceased loved ones. More than just remembering, it is an opportunity to reflect and celebrate a deceased person’s lifetime and memories.

What is most noteworthy about this holiday is that, despite its seemingly morbid origins and imagery, it is quite a festive and joyous occasion. Mourning a loved one certainly has its place, yet it is something that occurs all year around. This is a day to celebrate and, as such, it is a much more joyous holiday than its subject matter would suggest. This is not to imply that Mexican culture as a whole views the mourning process drastically different from the Anglosphere.

Much like Halloween, the modern observance of Day of Dead does not have a single clear origin; but rather it is an amalgamation of both Aztec and European influences. The oldest and most recognizable aspect of this holiday is that of the Ofrenda. This is an altar that serves as a memorial for deceased ones and, depending on the household, offerings may include traditional pan de muerto, or the deceased's favorite snacks. The prevailing color in this holiday is the color orange. This color is already strongly associated with leaves in the season autumn, and pumpkins for Halloween, yet for Day of the Day, there is a specific flower that is important for this day. Known as cempasúchiles, or marigolds, these flowers are native to many states in Mexico and have been used for medicinal purposes since Aztec times. Rather fittingly, the contrast of healing versus the symbolism of death is thematically appropriate for this holiday, as healing is a vital step in grief and acceptance of death.

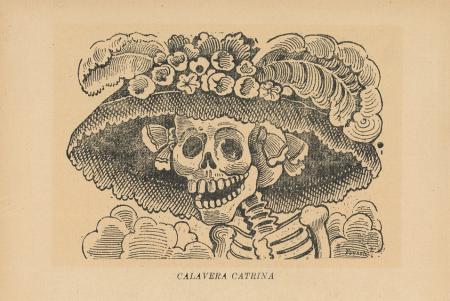

While traditions of honoring ancestors goes back into Pre-Columbian Mexico times, the most recognizable elements of this holiday are much more recent than one would think. For one, the iconic imagery of skulls is based on Mexican printmaker Jose Guadalupe Posada's 1913 etching La Calavera Catrina (often translated as “The Dapper female Skull”), which consists of a smiling skeleton wearing a large floral hat. This in turn was influenced by the deity Nuestra Señora de la Santa Muerte, a female skeletal personification of death much like the Grim Reaper. This depiction, also relatively recent, did not enter the popular consciousness until it was discovered by anthropologists in the 1940s. The worship of this deity remained clandestine until then, where it is now seen as antithetical to the veneration of the Virgin Mary by Mexican Catholics. Despite this, the Santa Muerte imagery has prevailed alongside traditional skulls signifying death (as is the case with the Grim Reaper) that are mostly European in origin.

Another recent popular aspect is the folk song “La Llorona.” Based on the folktale of the titular La Llorona (or crying woman), who is cursed to roam the mortal realm eternally searching for her children, whom she herself drowned. Traces of the actual legend reach back as early as 1550 in Mexico City, yet the legend carries many similarities with Aztec myths such as “The Hungry Woman,” who is depicted as roaming and crying for food. Regardless, the song gained popularity in 1941 by composer Andres Henestroa, where it soon became associated with the holiday, due to its themes of death and the inability to forget, but also as a warning of spirits being stuck in an eternal state of haunting if proper respect is not met.

While this holiday was already well known in many parts of the world, in recent years, Day of the Dead has surged into public consciousness due to its depiction in many popular Western films. Take, for example, the 2013 James Bond film Spectre. This particular film opens with James Bond on a mission in Mexico City, during a Day of the Dead festival. Interestingly, this festival was created purely by the filmmakers, as such a parade did not exist at the time of filming. However, public and tourist interest led to the Mexico state government creating such a parade in 2016.

Furthermore, we have the animated films The Book of Life and Coco, produced by 20th Century Fox in 2014 and Pixar in 2017 respectively. Both films take place in Mexico in small towns where family and remembering dead loved ones serve as the core themes; and include an afterlife where the deceased are portrayed as brightly painted calacas. It must be noted, however, that this depiction of the afterlife, referred to as “The Land of the Remembered/Forgotten” in The Book of Life and “The Land of the Dead” in Coco, are also pure inventions for the sake of the individual films, and have no basis in real life beliefs. One must keep in mind that approximately 78 percent of individuals living in Mexico identify as Roman Catholic. As such, biblical interpretations of the afterlife, such as Heaven and Hell are much more abundant.

Despite this, it is interesting that the film The Book of Life chooses to depict the rulers of the afterlife as La Muerte and Xibalba. The former is clearly inspired by the aforementioned Santa Muerte, while the latter, takes his name from the underworld in Mayan mythology. This depiction is one of the few explicit references to Mayan beliefs, as the Mezoanmerican influences, especially Aztec ones, have largely been downplayed in modern imagery.

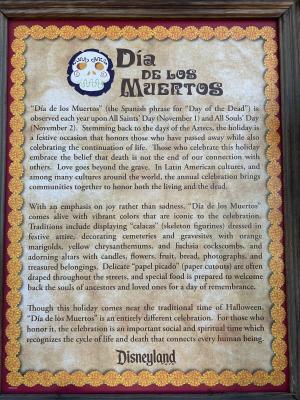

Much like Christmas movies such as Home Alone and A Christmas Story, the above films are meant to celebrate Mexican culture and The Day of the Dead, but on a purely secular level. The focus on all these pieces of fiction are on family, which is definitely a more universal theme. The universal focus on family is most apparent in how the theme park Disney California Adventure celebrates this event at Halloween time. A section of Paradise Garden Parks, near Pixar Pier, is rebranded as Plaza de la Familia, and a musical number celebrating the Day of the Dead is performed several times throughout the day. This performance consists of mariachi music, folklórico dancing, and puppetry with calacas and Coco protagonist Miguel playing the guitar. Despite the layered cultural and religious histories of these practices, the performance focuses on family, and even moreso on a generic celebration of togetherness. The concept of death is somewhat tiptoed around, and the calacas are presented as a “fun spooky” vibe more fitting to the safe Disneyland aesthetic.

El Dia de Muertos serves as a visual culmination of Mexican culture, combining Aztec roots and Spanish colonizer influences. While Mesoamerican mythology has all but disappeared in favor of Catholicism, the myths are still felt in The Day of the Dead. The fact that more modern concepts, such as the “La Llorona” and Santa Muerte noted above, are preserved in this holiday, ensures this day of remembrance and reflection is the perfect lynchpin between past and present.

Aldo Alcala '25

English Major / Creative Writing Minor

Religious Studies' Intern, Fall 2024

Image 1: Santa Muerte statue south of Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, Mexico

Image 2: La Calavera Catrina, 1910 etching by Jose Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913)

Image 3: The Storytellers of Plaza de la Familia Celebrate The Musical World of Coco! at Disney California Adventure, Anaheim CA

Image 4: Dia De Los Muertos sign near ofrendas at Disneyland Park